Work is the most consumed, yet least designed, experience on the planet.

Adults spend half our waking hours working. That adds up to more than 8 trillion hours per year across all of humanity.

Few experiences occupy such a prominent role in our lives. When asked to describe yourself, how quickly do you name what you do for a living? And yet, the design of this experience has been largely neglected. Why?

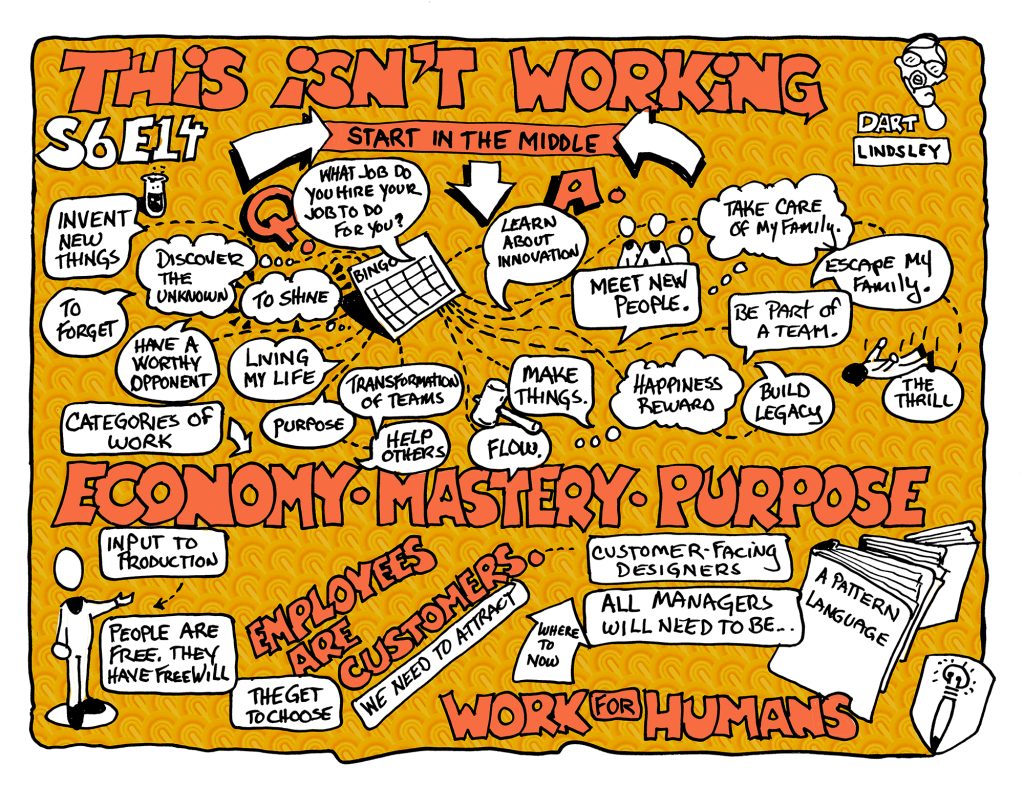

Dart Lindsley is Head of Process Excellence at Google and the host of the Work For Humans podcast. He has a radical idea for how to approach work, looking at it the same way we do a puzzle. He argues that the root cause of our problems lies deep in a relic of the industrial age: the mistake of thinking of employees as things.

Instead, we should be asking what job you hire your job to do for you, examining the flawed mental model at the core of un-designed work, recognising employees as customers, and moving towards a pattern language for the experience of work.

What Job Do You Hire Your Job To Do For You?

A bit of a head-spinner on first look, when we consider this question deeper, it’s quite simple.

Your job hires you to do something for it. But what do you hire it to do for you?

The answers are as varied and wide as people are. You might hire your job to:

- Fire my curiosity

- Help me learn

- Structure my life and give my days shape

- Give me something to talk about at parties

- Meet new people: not just anybody, interesting, intelligent people that will excite me and help me learn

- Sharpen my skills

- Help me figure out where I want to go next

- Be my creative medium

- Take care of my family and myself

- Be part of a team

- Make things: provide the tools, toolshed and materials

- Happiness/reward: not just what I get from it, but the experience I have doing it

- Feel a sense of flow

- Transformation: to make others shine, to broaden my horizons

- Keep me accountable

- Pay my bills

- Provide money for other experiences

- Help others: make the world a place I want to live in

- Escape my home life: kids/elders/in-laws, or my spouse needs me out the house

- Achieve independence

- Discover the unknown

- Give me messes to tidy up

- Pay my debts: not just financial, but also to the people who helped me get here

- For a worthy opponent: office politics, defeating the villain

- Grant me membership to exclusive clubs

- Spend time with my friends

- Invent new things

- For the thrills: ups and downs, working for start-up, feeling of jumping out of plane

- Build my legacy

- Repair broken things

- Give me puzzles to solve

- Do the books: so someone else can do the accounting for me!

- Be my stage and my audience

- Make me look good

- Make me unique

- Forget

…and on and on.

Famously, according to psychologists the three things that people most want from work are:

- Purpose

- Mastery

- Autonomy

However, this list doesn’t look like that. In fact, people rarely say autonomy. This is because the structure of the question “what do you want from work?” doesn’t invite the right answers. The question “what do you hire your job to do for you?”, however, is far richer, broader, and ever evolving.

“It’s a marketing question. If I’m going to design something for you, the best question to ask is what you want to get done with it.”

Dart Lindsley

This begs the question: why have industrial and organisational psychologists always ended up with purpose, mastery and autonomy, and yet this list is so different?

The Employee-Customer & The Multi-Sided Business

So how did we get here?

Over the last 100 years of work, people have been seen as an input to production, on the same level as raw materials, technology, and land.

All of these elements need to be bought, coordinated and improved to make them as productive as possible for customers, who provide revenue. This traditional pipeline model takes materials as inputs and transforms them into a product that they can sell. But this has never been right.

In this system people are referred to as “human capital”, or “assets” that are acquired. It’s considered a compliment when a CEO says “people are our most important asset” – but this is still a language of thinness. We talk about parts: butts on seats, headcount. Talent is seen as the part of a person we want to extract, and an employee as one who is used.

This tradition of people as inputs to production has blinded us to a bigger truth: unlike the other inputs, we are free. People get to choose what they do, when they leave it, and if they’re going to pay attention.

Freedom transforms people into something they’ve never been recognised as at work: customers. Customers exchange value with a company and are free not to. And if employees are customers, every company is a multi-sided business as it serves at least two types of customers, all of which have to be satisfied in order for the company to be successful. Uber, Airbnb and other sharing economy companies are multi-sided, but so are gaming consoles, credit cards, street markets, ad-based media, and beyond.

Moving From A Pipeline Model To A Platform Model

Seeing employees as customers changes everything. It means we’re no longer working from a pipeline model, but from a platform model.

In a pipeline model:

- Single-sided business

- Workers are an input that is bought (they don’t want to do it)

- Work is a cost to employees

- Companies acquire and maintain label

- Uses tools from psychology (how can we get the most out of you?)

- Humans for work

In a platform model:

- Multi-sided business

- Workers customers who are won (work has value)

- Work is a product employees buy

- Companies design, deliver and build a work experience

- Uses tools from marketing and design (what do people want from work?)

- Work for humans

If Work Is A Product, We Can Design It

If work is a product, it’s a very sophisticated one. It consists of a good, service, experience, and relationship, all of which are true at different times. It’s a company’s job to design and deliver a work experience that will help people feel whole and alive.

We need to change the way that companies think in order to transform their business models and invest in producing work experiences products that will win the employee customer.

One crucial thing that changes in this new model is the role of managers. They automatically become customer facing, as their teams are now customers. Every manager becomes a designer dedicated to the mission: I know what work I need to do to win you. Work needs to become flexible enough to work for employees in their world, and the manager has to become adept and balancing the demands of the business and the demands of the employee-customer.

“Even the word manager is terrible. Organisational charts should be inverted: managers should be at the bottom as support and individual contributors should be at the top, as that’s where the growth is.”

Dart Lindsley

At present managers drive productivity, rather than letting employees grow. Lindsley tracks work over three dimensions to try and counter this:

- Does it have business value?

- Are we producing the value we are most qualified to produce?

- Is it rewarding to you? How much fun are you having?

The answers are ranked from the top (“I’m in flow”) to the middle (“I’m eating cupcakes”) and the bottom (“I’m walking on glass”). If something falls in the yellow, it’s discussed and an action is taken, whether that’s swapping projects or getting rid of a project entirely.

However, most managers don’t have a language to understand people in this way. So how can they begin this process of change?

A Pattern Language For The Experience Of Work

A Pattern Language is one of a series of books by Christopher Alexander that looks at the vocabulary of patterns in architecture. Alexander felt that modern architecture fails to make people feel whole and alive – but traditional architecture that’s been incrementally modified over the years has discernable patterns that do.

He and his colleagues set out to list all 253 patterns in architecture that just work, from ring roads to front porches to living-room chairs. When you read them, you recognise them. Things that work in a garden, for example, include: a garden growing wild, a trellised walk, a garden walk, a garden seat, a vegetable garden, and a compost heap. A child cave “needs to exclude adults, be about 5×5 so 4 people can play in it, and stand between 2 and 4 feet tall.” There is a grammar that connects these different architectural patterns together.

Designing Work Like A Puzzle

It’s possible to create a pattern like this for work. For example, if someone wants their job to “give them puzzles to solve”, we can look at the design attributes of great puzzles. Why is it that you can see sudoku or crossword puzzles in your newspaper, and not algebra puzzles? It’s because they have recurring features, namely:

- Great puzzles have a clearly correct final solution – you know when they’re done.

- They’re difficult, but not impossible – we can stand about 10 defeats to every 1 win, but only if we get the win eventually.

- Self-contained, because this is a test of my wits. If it’s a test of finding the reference or with a calculator, that’s not what we’re trying to do.

- They contain incremental wins: if you had to sit in front of a jigsaw for three days and do it all at once you probably wouldn’t, but there are little wins and losses throughout. There’s a narrative structure.

- They provide a glimpse into the eternal – can see past them to Pythagorean perfection you love to look at.

- They’re beautifully constructed: you can’t believe anyone ever made one crossword, let alone every day.

- They can be solved elegantly.

We can bring all of these patterns into the workplace.

- For example, rather than having “big, mushy” projects that no one can quite see the point of, state clear outcomes. This is one of the reasons that the deluge of never-ending emails is a design flaw of modern work, whereas projectising work can provide structure and help people feel good.

- Identify incremental wins and call them out when you see them.

- Admire the beauty of the problem you’re facing, and take time to do this as a team. People like working in teams because the outcome is a surprise: they are building discovery, as well as amplifying their work.

- Make the challenges hard enough to be interesting – can you not only solve this puzzle, but the “meta-puzzle” that would work for all similar puzzles?

- Make the last piece, or “the detect”, very clear, and something more specific than a feedback loop, so people know the project is complete.

“If I’m a manager and my job is to broker between the needs of the business and my team, this pattern language helps me hear what you need. If I know you want to solve puzzles, I have a deeper understanding of how to develop puzzles for you, for example.”

Dart Lindsley

Most companies already know they should – and want to! – do good things for their employees, but are stuck using old tools. They can pay you more, and give you perks like gym memberships or unlimited snacks, or they can give you less work. These are the levers that we use when we’re buying something, but they don’t recognise the whole human – or that work can actually be valuable. To effect real change means buying into an entirely new business model.

“With change management, the physics of it is like a giant trampoline covered with marbles. A big idea is like putting a rock on the trampoline: the marbles don’t move. It only changes the shape a bit. But if I can put my finger right next to a marble, I can make it go wherever.”

Dart Lindsley

The WXO Take-Out

We love the radical simplicity of Lindsley’s approach, flipping the basic question of what we want from work into what we get out of it, reframing employees as customers and work as a product that can be designed.

“I once talked to an experience designer who said you could design work like a toaster, and I said: a toaster has never put me in therapy!”

Dart Lindsley

By placing care, trust and belonging at the centre of work, recognising the different needs that employees have, and moving the role of management from driving productivity to fostering growth, we can move to a new system that pays out on both sides.

We also love the idea of a “pattern language” and designing like a puzzle, and wonder how this might be applied more widely than the employee experience. What might a pattern language for experiences look like? (Perhaps our WXO Certification will provide some answers when it’s revealed…)

So next time you’re designing an employee experience or thinking about your own workplace, ask yourself:

- What job do you hire your job to do for you?

- What isn’t working in your own work?

- Do you think of your employees as customers? Why/why not?

To see the full line-up for the WXO Campfires Season 6, click here.

To apply to join the WXO and attend future Campfires, click here.