What coming face to face with my fears taught me about experience design – in particular:

- Why you should ‘design for disclosure’

- The value of breaking the rules

- How the real world is never as clean a hero’s journey as we’d like to think.

On Saturday October 15, as I sat in the shade by a roadside diner in Utah, sipping a cheesecake milkshake, the man responsible for making me cry asked me:

“So, James, would you call that a ‘good experience’?”

Brian Hill is a pioneer in experience design, a professor in Experience Design And Management, and gives the most popular class at Brigham Young University – on how to live the good life. So I was a bit surprised that he was asking.

Still, he did. So, here’s my brief analysis…

Opening The Experience Toolbox

There are many approaches to good experience design, but most follow some version of:

“Before > During > After”

And

“Beginning > Middle > End”

Then there are the checklists.

4 Extraordinary Experience Design Checklists

One: Paul Zak’s S.I.R.T.A. is based on more than 15 years of neuroscience research, and in his new extraordinary new book…

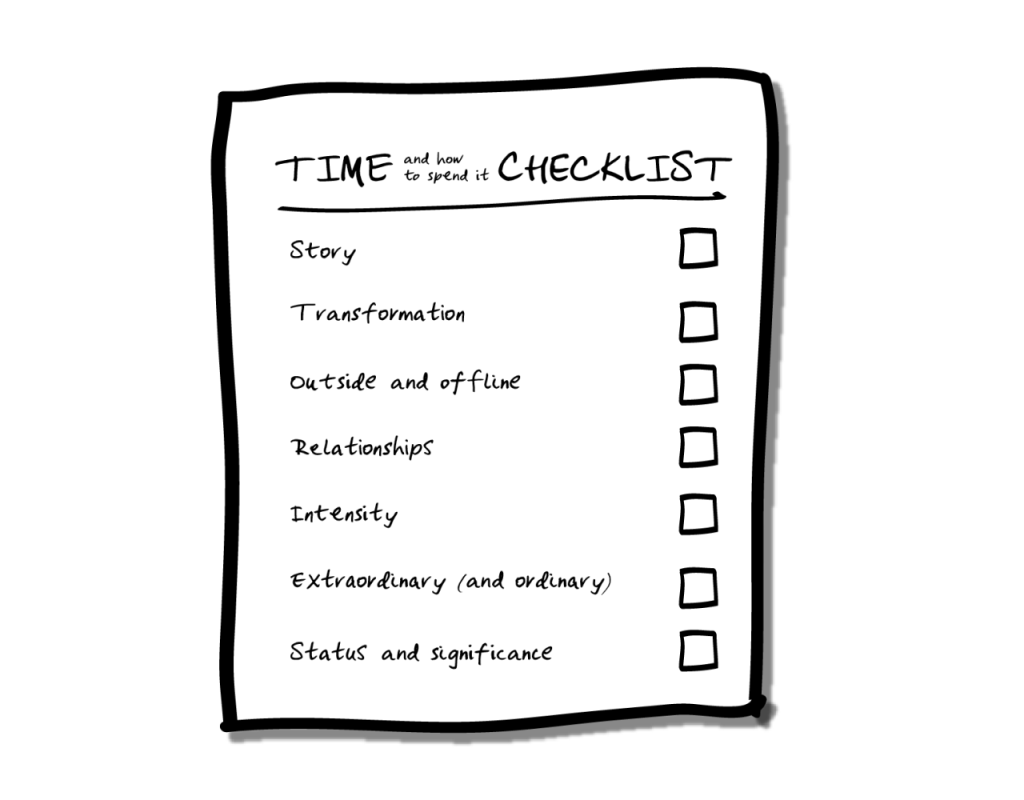

Two: S.T.O.R.I.E.S., based on both decades of research and the latest psychology, from my book Time And How To Spend It:

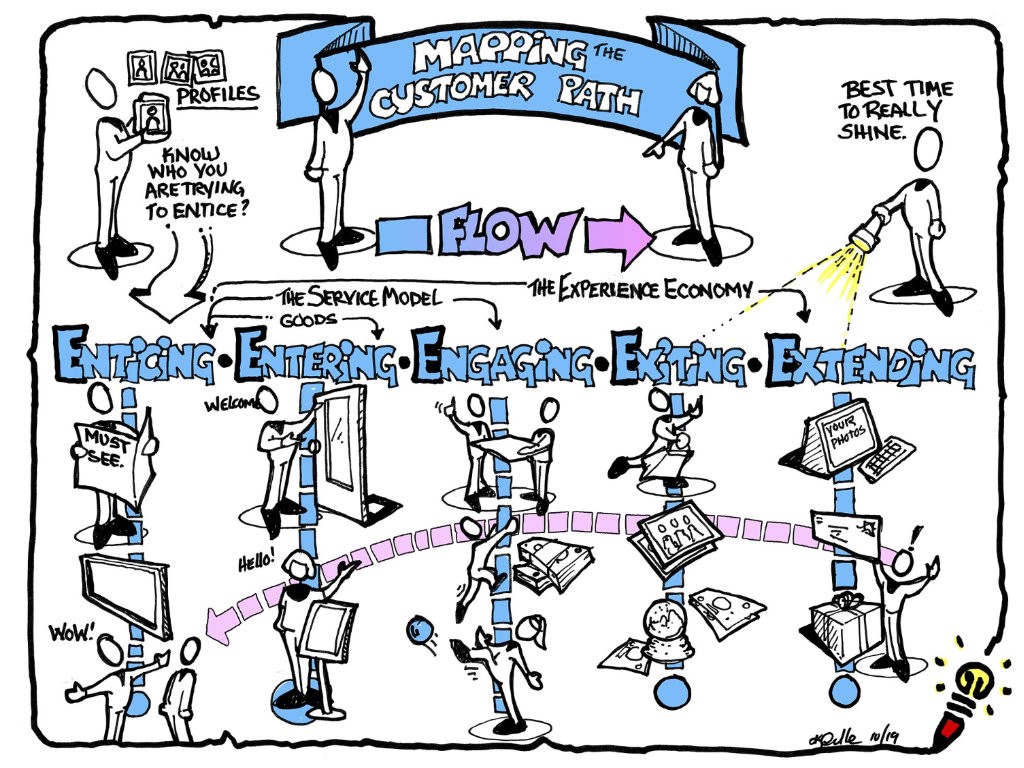

Three: Joe Pine & Jim Gilmore’s 5 Es, from their classic The Experience Economy:

Four: Anton Jerges’ new MARVELS – coming soon to a WXO Campfire near you!

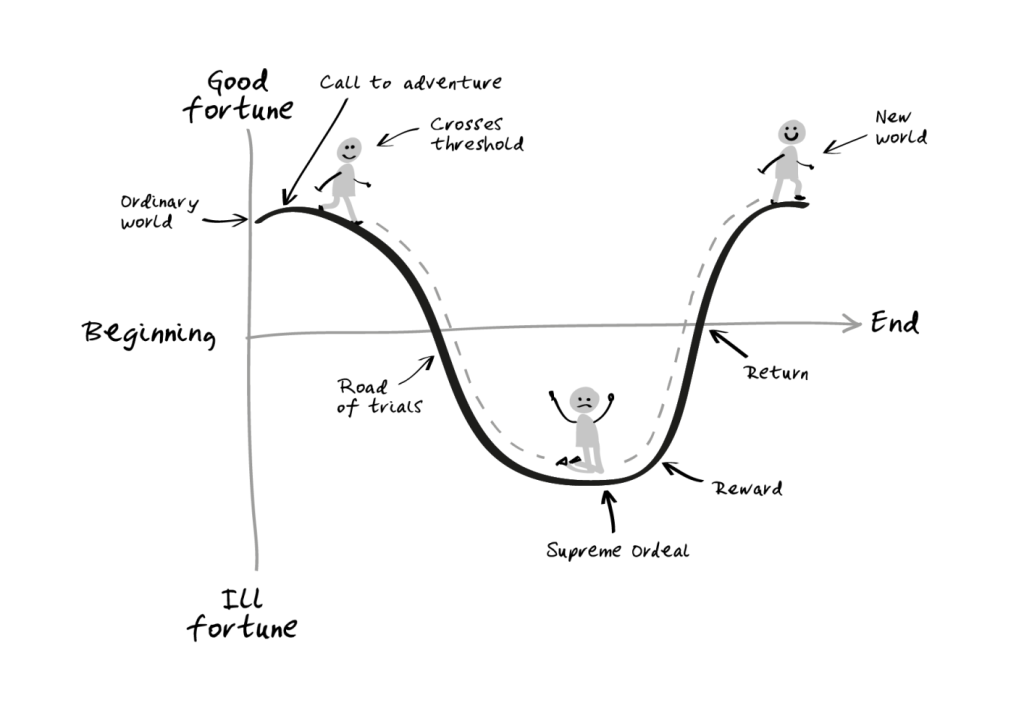

Then, beyond the checklists, there are the journey maps. The classic is the Hero’s Journey.

Or you can draw the ‘hole’ as a ‘mountain’… the key is that Something Happens.

Or use Freytag’s pyramid, if you prefer Joe and Jim’s focus. And I’ll refer to elements of these, especially the Hero’s Journey.

But the one I’m focusing on here is a model from Mat Duerden and Bob Rossman, who wrote the brilliant Designing Experiences:

“Anticipation > Participation > Reflection > Integration”

As with any tools, in the hands of the amateur they can be a straitjacket. They’re not supposed to be slavishly followed – and as you’ll see in this analysis, they can be mixed and matched.

Anticipation: Leather Gloves And A Good Breakfast

Anticipation 1: OK, so I’d chosen ‘canyoneering’ out of the optional extras at the end of the 7X Summit conference. But still, it’s the first time pre-conference guidance has told me to ‘bring leather gloves’.

Anticipation 2: At the end of the conference we went to a local canyoneering spot.

It was ‘only’ 70 feet or so, next to a waterfall. A useful introduction, as I would never have managed the first descent of the next day.

Anticipation 3: “Have a good breakfast,” said Peter Ward, Brian’s co-pilot for the day. “There’s nothing up there, the air’s thin, and you don’t know how much energy you’ll need.”

Crossing The Threshold: Dark Car Park

We met before sunrise, in the quiet dark of a university car park.

Anticipation Continues: The Utah Valley And Red Rocks All Around

We drove for three hours along the valley. It was a great chance to see the vast Utah valley, the flat plains, edged by green, orange and red mountains.

We stop to shop. Shopping for snacks, with friends, in a place where the snacks are so different – bigger, better, sugarier, more American – is so far removed from the weekly shop. It’s bonding –in a light way, perhaps, but still a part of the puzzle. We found ourselves discussing snacks, then sharing them when back on board.

Eventually we came to the place: walls of red rock, hundreds of feet high, called ‘Capitol Reef’ because it was considered impassable by the pioneers when they first came here in the 1840s.

We park, walk up for an hour or so: to marvel at the views, get used to the height and get into the scenery.

Anticipation / Arrival: Looking Down, No Turning Back

Arriving at the top: views across, yes, but also down. 150’ down…

Crossing The Threshold: Just Once Unto The Breach

There can be few experiences that truly reflect the beginning of the Hero’s Journey so well as stepping over the edge and into the abyss. Inside, I desperately wanted to refuse the call to adventure.

But with the help of a mentor – Brian – a rope, the relevant canyoneering kit, gritted teeth, and the driest mouth I’ve ever had (and I’ve been on primetime TV and given a talk in front of 2,500 people), I shuffled over the edge, and crossed the threshold into this adventure.

B.E.E. Rules: Shouldn’t You Build Up To A Big Moment?

I’m still not sure what I think. This was one helluva beginning. We dropped into 150 feet of nothingness. Beautiful nothingness, surrounded by red rock and ridiculously stunning views. But it was the biggest drop of the day. Surely the hero’s journey says you build up to this sort of thing? Have a few smaller tests first?

Still, beginnings are especially memorable anyway.

(The B.E.E. Rules is myupdate on the Peak-End rule. Beginnings, Extremes, and Endings. Because Beginnings also have an outsize effect on what the ‘remembering self’ remembers – i.e. beginnings are key for memories.)

So why not sometimes turn up the volume and make them even more so? (Actually, as Victor van Doorn once said, ‘just beware that the beginning doesn’t outshine the end’. He once had an experience where that happened, and the balance spoiled the experience.)

As I sat on a rock, ready to go, my head and heart wanted to be anywhere else.

“Brian,” I wanted to make sure he was looking at me, “I think I’m gonna cry.”

“Well, alright then,” was his simple reply.

Early Integration: Rappels That Were Easier, But Weirder

After the peak of the hero’s journey, there’s usually a moment for the reward. Then on the down cuve we expect to see integration: a chance for the hero to test their newfound skills.

And that’s, sort of, what happened. After that first drop into the unknown, we were transformed into canyoneers, with new confidence and the skills to try it out.

None of the next rappels were as Insta-scary as the first. But each had its own challenges and strangeness.

The Birthing Canal: you had to clamber down awkwardly, sideways, mostly while laughing, and remember to keep one hand holding the rope.

The Bridge: you had to go face first down a sort of slide, then spin round and swing down into a cave.

The Knife Edge: you had to walk down a 70-degree slope that just stopped, like a knife edge. To not just slam your face into the rock, you then had to lower your bum below your feet. One of our crew – Aga’s Lukasz – ended up upside down.

Let’s remember some of the key ingredients for extraordinary moments that stick in our memory. ‘FANU’ is the (rubbish) mnemonic in my book Time And How To Spend It, as in Flow, Awe, New, and Unpredictable. Somehow each one of these rappels was new and unpredictable. We were indubitably in flow as we concentrated.

And awe? That’s coming…

Crossing The Second Threshold: Cactuses And Awe

After the last rappel, we slipped out of our harnesses, took a swig of water, and clambered the path. Within moments, we were bent double, heading into a west-facing cave bathed in a sort of mango light. Then out, and through sandy desert lands carpeted with low-lying cactuses.

On each side, smooth red-rock towers above us. They’ve been cut and smoothed by wind, water and more time than a human can realistically imagine. We can’t help, every now and then – and despite the inner glory of the veni, vidi, vici post-flow feeling – to look around and feel so, so small.

And so we walked back to the van. If we’d gone in like a bunch of acquaintances and kind of friends, we’d come out as a band of brothers and sisters. Yes, that sounds corny, but we’d egged each other on, felt each others’ fears, and held the rope for each other so that we wouldn’t slide to our deaths. We’d been through something.

An Overlooked Ingredient? The Surprising Magic Of Disclosure

If you’re reading this, you’re probably interested in experience design. How often do you design for disclosure, for people to show their vulnerability? Well, maybe you should.

Brian’s seen it in the study abroad programmes he teaches. He’s seen it on the overnight camping trips and rappelling days out he leads. With the study abroads and camping trips, there’s an element of disclosure built in through reflection exercises. But there isn’t a deliberate ‘designed’ reflection exercise. But, Brian told me, disclosure just tends to happen naturally, and that leads to real bonding.

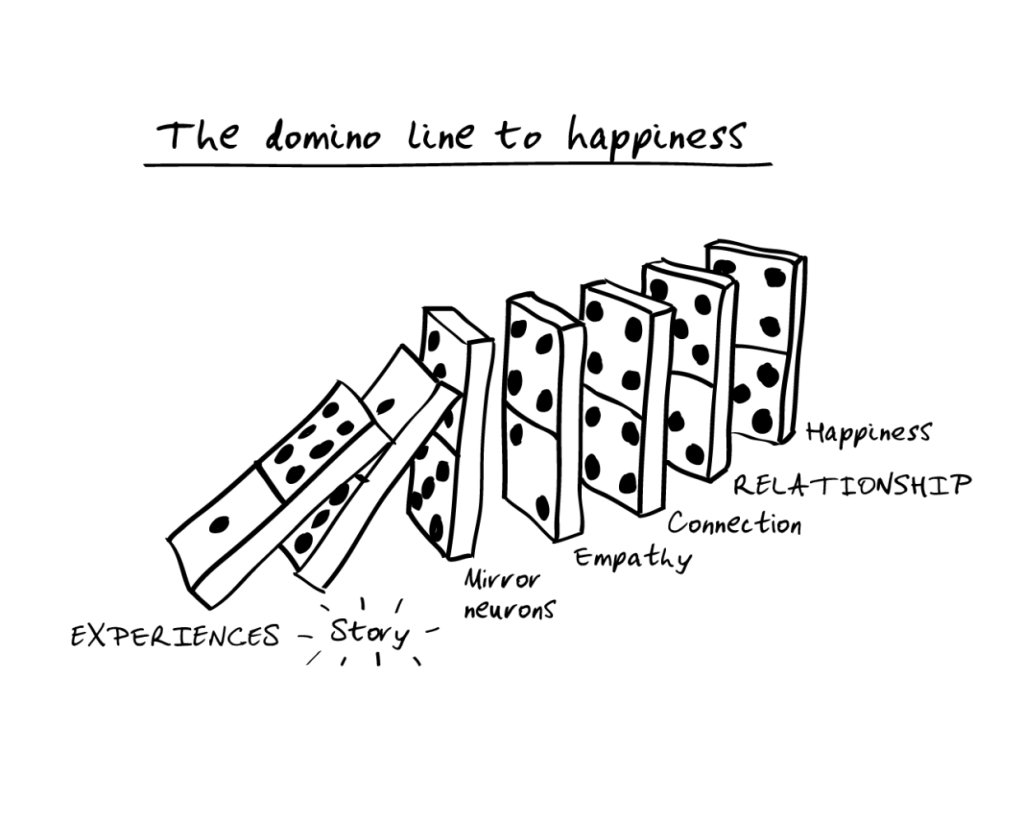

In my book Time And How To Spend It, I talked of the ‘domino line’ to happiness that happens because of stories.

(While many believe in ‘mirro neurons’, Paul Zak disagrees with this explanation. His take is that the key mechanism here is how stories flood us with oxytocin, the ‘love drug’. And that’s the thing that creates these bonds.)

I think the most curious question here is: what is it about these sorts of experiences that makes disclosure happen? And how can we design for it? Is it discomfort and fear? Is it facing a shared enemy, helping each other through? Is it the intense seeing and being seen, beyond the veneer of our typical ‘how are you?’ ‘I’m fine’ exchanges?

And, crucially, how can we design for that? To give as many people as possible the sense of belonging that comes from these sort of transformational experiences.

Anyway, we got back in the van. On the journey, one of our gang shared some childhood trauma. Tears flowed, hugs happened, and we bonded even more. As Brian got out of the car, he noticed, and I swear I saw a wry smile on his face.

Conclusion: Remember That The Hero’s Journey Is Different In Real Life

The hero’s journey reflects an evolved shape of story that’s been honed and perfected over millennia and is therefore ever so slightly artificial.Real-world stories rarely follow the exact pattern – and that makes them even realer.

These deviations from the perfect pattern aren’t a problem. And the skilful experience designer / operator / stager doesn’t fret about them. They’re just part of the design challenge. Consider, for instance, the trip in Morocco I’ve designed for New Scientist Discovery Tours.

Tying in Marrakech, a trek up Mount Toubkal and all the other pieces was hard to design. It was the same with canyoneering. The peak moment was arguably in the wrong place. The ending was… just an ending. The topography wasn’t designed – amazingly! – for humans to play on. That red rock was carved by wind and water over a long time.

But an exact shape isn’t the point. The carving and analytical tools of experience aren’t either. The impact was clear: we came, we rappelled, we bonded. And along the way, we made friends and memories that’ll last our lifetimes.

So, Brian, thanks.

Post-Script: We Almost Flew That Day

The next day on the plane home, I suddenly remembered a poem I’ve taught my kids. It’s called ‘Come To The Edge’ by Christopher Logue, and it goes like this:

Come to the edge.

It’s too high.

Come to the edge.

We might fall!

COME TO THE EDGE!

And they came,

And he pushed,

And they flew.

We didn’t fly that day though. The rope held us.