Wondering what an “open-world experience” actually is?

If you ask Nick Moran – who some say is in the top 5, or top 3, of escape room designers, depending on the time of day you ask – he might tell you that it’s an essentially meaningless term that does nothing other than help to define a certain type of experience.

However, we’d say he’s being modest – and that in fact, an open-world experience is an exciting new concept best described in the words of fellow WXO Member Ramsay Wood as a “non-linear site-specific narrative”. Or in other words, a place where people come, roam around, do quests, solve mysteries, eat and drink, and leave – and in the case of a good many of them, return to do it all again.

In the case of Moran’s newest experience, Phantom Peak, for example, 70% of people stay until the very end of its 5-hour run time – and 30% come back again.

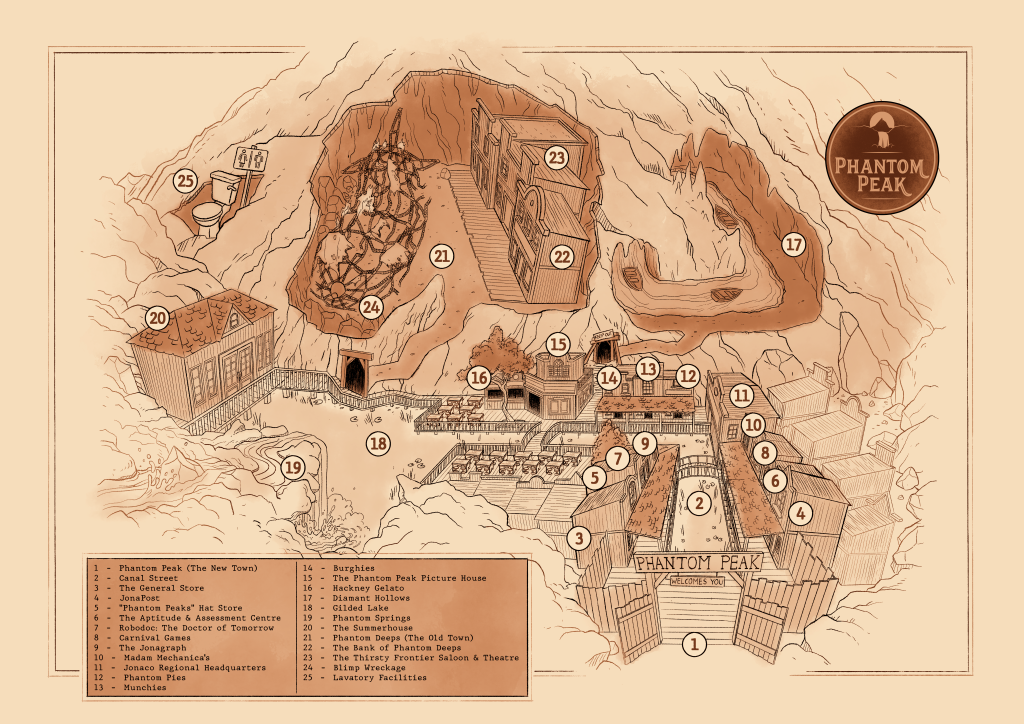

The open world of Phantom Peak combines theme park, escape room, dining and immersive theatre elements to create a miniature Western town. Guests explore it at their own pace across five hours, 50 different plotlines (and counting), and a cast of 25 actors. There’s also fairground-style games, bars and food outlets, shops, and even a boat ride.

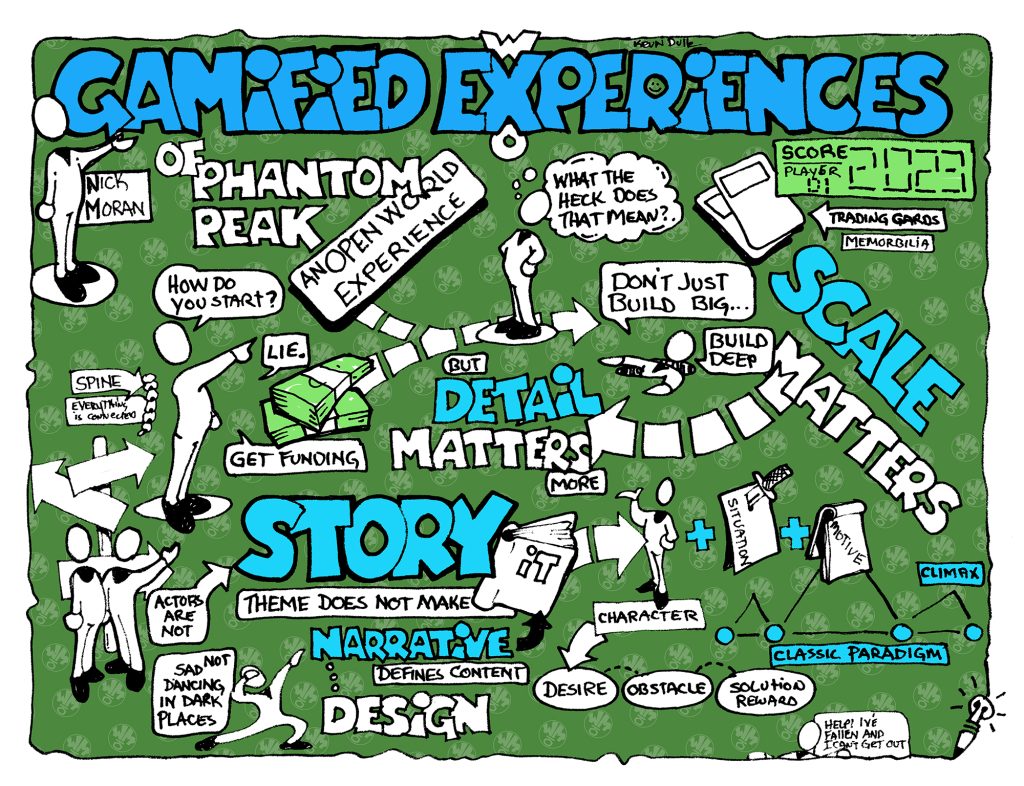

Moran made us laugh and think when explaining the secret sauce of Phantom Peak, teaching us that only charlatans are into the Hero’s Journey, sad dancing does NOT equal story, and that for a world to feel alive, it has to be fundamentally narrative driven.

So if you’re interested in building an open-world experience – or just an experience with the depth, creativity and repeat pulling power of Phantom Peak – read on.

Don’t Just Build Big: Build Deep

So how do you make a world like Phantom Peak? The answer is… get as many mortgages as you can!

This is a half-truth: it’s true that Phantom Peak is big and complicated to put together. But according to Moran, an open-world experience isn’t just about building big: it’s about building deep by paying attention to both scale and detail.

“This is where things often fall down in our industry. Spectacle is really important, but often it’s not what captures us and brings us back.”

Nick Moran

Phantom Peak operates seasonally and 30% of visitors return each season, which is very rare. They’ve invested in the world – but why? Moran thinks the answer is simple: stories.

What A Story Isn’t

When it comes to stories, the experience industry is full of snake oil. The people who say they can do it might be good in a brainstorming session. They might be creative directors, who want to capture “the feeling of Black Panther mixed with the gender politics of Little Women”. However, writing or creative direction aren’t the same as storytelling.

Some things that aren’t a story include:

- Lore. That’s just an appendix! No-one can consume it.

- A situation, e.g. a bank heist.

- A really cool set. Sets are really important, but they’re not stories.

- A character shouting at you about how important something is.

- Some really loud stuff happening super quickly.

- Random puzzles that do things.

- Some projections that wobble a lot. This is in and hip – see Monet, Van Gogh, Klimt, and a host of others. However it isn’t a story, it’s a timeline.

- A theme, e.g. capitalism = bad.

- Voiceovers that talk about feelings.

- Actors in general.

- Actors in specific, when they are just characters.

- Videos.

- Loads of bad copy written by someone tired a few days before launch.

- Loads of good copy written by someone who thinks they are / actually is the next Great American Artist.

- Food.

- Sad dancing in a dark place – which is incomprehensible, has no context, etc.

“For a world to feel alive, which is the objective of an open-world experience like Phantom Peak, it has to be fundamentally narrative-driven.”

Nick Moran

This doesn’t mean that all experiences have to have a story, or that all wobbly projections are bad.

“I agree that some immersive art exhibits are not good, but I also think there’s real value in them. They can be an on-ramp into the immersive space. Not every production has to have the same goals.”

Laura Hess

However, when it comes to an open-world experience, stories are central.

“I wouldn’t bother making Van Gogh anything other than a nice spectacle for the eyes. My problem comes from the pretentiousness that everything has to be sold as a series of stories, when it’s really just nice projections. This devalues people who are making good immersive stories and confuses the consumer.”

Nick Moran

How To Build A Story

There are some tried-and-tested principles for building a story that do work, namely:

- Dramatic action: the building block of what makes a story. You have a character that wants to change states. The problem in the world of experiences is that often characters and actions are functions – they don’t want change, so they’re static and don’t feel real. Story is like a gas: it’s always expanding and wanting to change states.

- The Classical Paradigm: this works experientially as it’s all about a world destroyed by a thing or idea that leads someone to a false conclusion. It’s about the journey of the characters, which creates empathy for the audience.

- Lots of other paradigms: such as the ironic paradigm, shown in Hitchcock’s film Rope. You can also combine them, as is done to excellent effect in The Truman Show.

Things like set and technology do matter, but it’s the narrative structure that defines the content. Set and technology are meaningless without this structure. It also helps actors with their performances, as they are defined by the stories, structures and status we give them. Otherwise, they’re just acting into the void and become functions, rather than functions of the story.

A game is also different to a film because of its story structure. It requires action in order to proceed: the character has to go on a journey of strength to become who they need to be and achieve what they need to achieve.

And the story doesn’t just have to make sense: the actors have to boil down their interactions into digestible moments.

- Step 1: desire – the character has a want.

- Step 2: obstacle – something is in their way, which players have to engage with to remove.

- Step 3: solution and reward – leads to a higher understanding.

How To Deliver Your Story

Once you’ve got your story, how do you deliver it?

- Delivery mechanisms. These are tools for knowledge, interaction and delivery that help people to digest chunks of the narrative. In-world devices are your friends here! In Phantom Peak, devices including the Jonaco Videomatic, Jonagraphs and Jonagam contain videos and written content to divide up the beats of stories. These need to have more than one function, or they don’t feel real – you can’t have a computer that’s designed to only play one video, for example. Don’t make static points: make systems that people can understand and use and that push along the narrative.

- Spine. There always has to be something that makes sure you don’t lose people within the narrative. In Phantom Peak, this is the Jonassist: a web app that was built so people could play the trails, randomising which trails people are assigned to so there aren’t bottlenecks in the experience. Sometimes it can be easy to get lost in side quests, or in the queue to buy waffles: the spine will tell you where you were and where you need to be. It also tells you when you’ve finished the storyline.

- Tight rules. When you build an escape room, it’s an intimate environment, so you have huge amounts of control. When you have 500 people, you have to do the work to make sure it’s digestible and understandable. Moran suggests building an escape room and getting your friends to play it, as you’ll learn the most by watching people experience the things you think are clear. For example, people under pressure don’t want to read! So make what matters obvious so they can get to the next story beat.

- A truly full world. The bigger the canvas, the harder you have to work to keep people’s attention. At Phantom Peak, the team works really hard to fill the world with trails, actors, food and drink to ensure people want to stay. No matter what it is, the detail is there for them to consume, whether active or passive. You’re competing with the entropy of people who want to go home!

Above all, make sure you do the hard work of setting up the story, understanding the mechanics of how to build the world, and getting stuck in on site to see how it works.

“You can’t be a designer unless you’ve been on site and slogged it, so you understand what is happening in the experience. It’s how I learned to make Phantom Peak better over time.”

Nick Moran

And finally, a word of warning to self-proclaimed storytellers:

“If you can’t design stories, then don’t – pay somebody who can! Story is one of these strange places where everyone thinks they can or should contribute, but they don’t have to. Get someone to do the structural work and build it from the ground up – not just physically, but metaphorically, too.”

Nick Moran

Story Is The Sea, Narrative Is The Boat

There are different schools of thought about what constitutes a narrative. For example:

“One element of narrative is structure, and the other is the deeper meaning, usually centred around big human themes.”

Pigalle Tavakkoli

Moran defines it slightly differently.

“Story is the world and narrative is the way you navigate through it. If you think of it from a nautical point of view, the story is the sea and the narrative is the boat. The world of Phantom Peak is a complex, strange, and hierarchical one. The narratives are all about the people within it, trying to deal with the things they encounter. Each season something has moved on in the town that affects all these characters and the way they deal with it.”

Nick Moran

It’s characters that people resonate with, not themes. When building these characters, Moran recommends building the world first, and then the characters will appear within it.

“I start with the things I know – the town exists, Jonaco is taking it over – and then the characters start writing themselves. Who would live here? How do they feel about it? Then think of status – who’s lowest? Highest? Who’s second highest? Who do they hate and why? If you do a questionnaire, the characters will reveal themselves. Start with questions, not characters.”

Nick Moran

Each character is the centre of their own world, which is what makes the town feel alive for the up to 500 people playing at the same time.

Extending Your Story Beyond The Open World Of Your Experience

Having a solid story that your narrative and characters spring from is key to creating an open-world experience. But how much should this story extend beyond the experience itself into the anticipation and reflection stages?

At Phantom Peak, the focus is very much on the time visitors spend in the fictional town itself. You’re told that you’re a tourist, which as well as neatly circumnavigating continuity issues with outfits, accents and so on, also means you can be invited in for the duration of the experience and have a clean exit at the end. (It also makes us reflect on AR expert Rob Morgan’s assertion that if you want to make someone think they’re a dragon, don’t tell them they are one – tell them they’re in a dragon’s cave.)

“For me, someone being part of the world when they don’t know it is disjointing. You’re from out of town – you can dress up, but you’re still a tourist. Everyone at Phantom Peak is part of the ecosystem of the town. Jonaco has a ranking system. How you fit in is important to how the story is constructed.”

Nick Moran

However, other experiences give you a role before you go in, such as Secret Cinema – see former its creative producer, Andrea Moccia, on how they set up this pre-event anticipation. This allows for a descending of steps into the experience as opposed to a blunt crossing of the threshold – as you move towards the location you begin to see more people dressed like you, for example.

And when you plant the seed of a narrative that your audience can tend to on their own to extend and expand it, you enable and empower them to live their own extended story. This can be a very powerful tool.

“As a creative, this is where we’re able to go from being true to our own intent to being able to let go of the impact. What can you do to give oxygen to the people so they can outlive the narrative – and potentially even influence what’s going to come with your next iterations? Our duty is to make sure audiences find themselves within our experiences.”

Lou Murray

We think there are some interesting ideas in Campfires 45 & 46: The 4-Step Plan To Transform Spectators Into Superfans about how to create a “ritual chain” that converts casual visitors into those who obsess about your experience within the context of their own lives, which could be applied here.

Another way to extend the world of your experience could perhaps be thinking about how it might translate within different environments. In the case of Phantom Peak, for example, how could you take past storylines and give them to different communities, like the HNW market?

“I’ve designed escape rooms on superyachts. The HNI are so bored – money is no object, but they want to be entertained. Experience is everything!”

Victoria Taylor

The WXO Take-Out

When we look at the dizzying scale, in terms of sets, characters and spectacle, that accompanies an open-world experience like Phantom Peak, it might look like an overwhelming task that requires deep pockets and huge teams.

However, Moran shows us that the difference between a successful open-world experience and a bloated, unfocused one comes down to one thing: story. This is something that requires structure, discipline, and clever delivery mechanisms to make sure your audience can easily understand and interact with the world you’ve created.

So next time you’re creating an experience, ask yourself:

- Could your experience borrow from other “experience genres”?

- How do you allow for individual choice within your experience?

- How could you create different, co-existing pathways through your experience?

To see the full line-up for the WXO Campfires Season 6, click here.

To apply to join the WXO and attend future Campfires, click here.