What does it mean to design experiences?

Traditional design practices invite us to design things, and to use those things to solve problems. But experience is not a problem: it is life. Experience designers engage with unpredictability and the unknown, partnering with their audiences to generate possibility and relationality.

This means we need a new set of tools to design experiences than we do to design things. We stand at an exciting, emergent point in the function of experience design. We’re not stepping into a set of best practices, but defining together how we might create worlds, craft narratives that enter people’s lives, and structure real transformation. If we use old tools, we’ll have old outcomes. But if we create new ones, the possibilities are untold.

Enter Abraham Burickson: experience designer, architect, and Director of Odyssey Works, an experimental performance group that creates personalised, immersive experiences for individual audiences. Burickson has been designing and teaching experiences for over 20 years, as well as consulting for entities including Apple, Facebook, and academic and religious groups. In his forthcoming book, Experience Design: A Participatory Manifesto, he boils down everything he’s learned into a set of 10 principles for experience design.

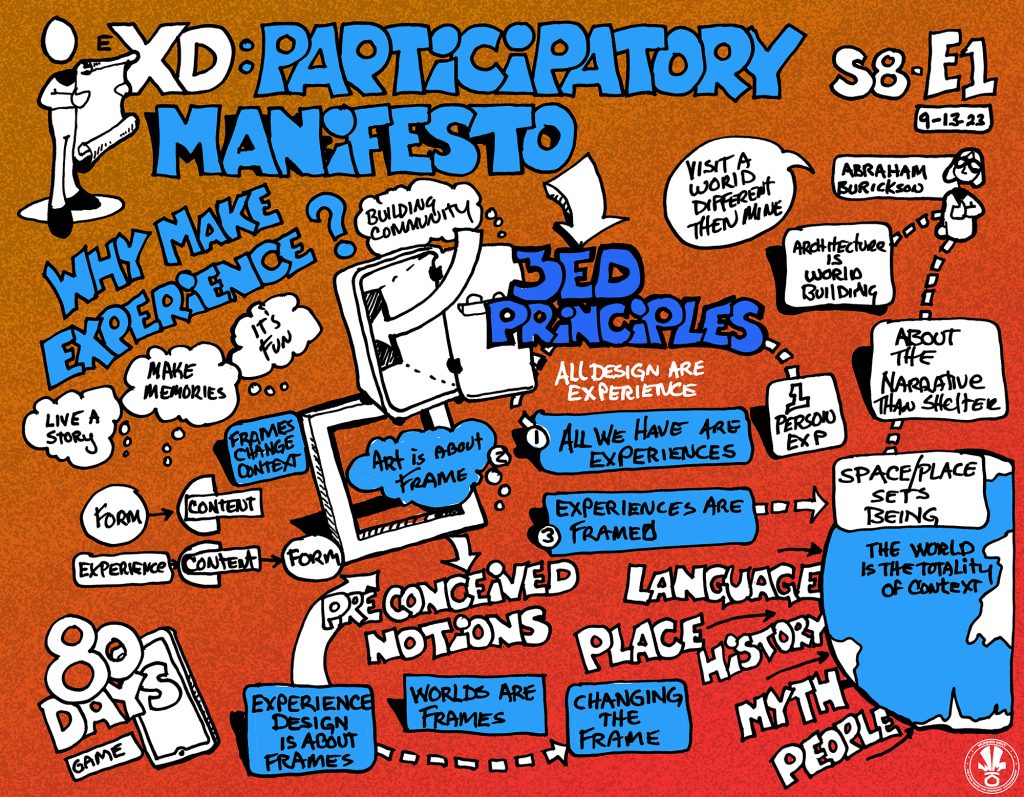

For the first WXO Campfire of the new season, Burickson shares three of these 10 principles that will change the way you design experiences – and make them more impactful, in-depth and transformative. Read on, and you’ll learn:

- Why other experience experts like you make experiences

- Why building a world means constructing the self

- The three experience design principles you need to create real change

- The importance of framing your experience

- The four key elements of worldbuilding

Get the full report below – and full WXO Members can view the video Campfire Catch-Up of Burickson’s talk HERE.

Why Do We Make Experiences?

Burickson began by asking this simple question to our audience of experience experts. The answers were both unique, and strikingly similar:

- To make life better.

“To show the world as it could be” “Because I think we can upgrade quality of life” “Giving gifts to others of enriched moments” “To evolve life” “Because experiences can accelerate positive change”

- To make people feel more.

“To help people feel” “To make people FEEL” “To make people feel more” “To make us feel alive” “To fire people’s emotions” “To fire people’s neurons and form unique memories” “Memory making”

- To create connection.

“It drives human connection” “To build community to bring humans together” “Emotional connection, social connection, indelible memories, fun, entertainment” “Connecting humans with themselves, each other and the natural world” “To connect with others” “To inspire connection with ourselves, our neighbors, communities, nature, our history and the universe” “Can allow you to live the story”

According to Burickson:

“We’re engaged in a practice that has a kind of hopefulness – these ideas are radical. They speak to a pain we suffer today: a lack of connection, narrative sameness, and lack of joy. There’s an ethical cord to what we’re doing. It represents the possibility of transformation and hope.”

Abraham Burickson

When We Build A World, We Design Who We Are

Burickson’s early training as an architect studying indigenous buildings taught him that architecture wasn’t just about doors and windows, but about spaces of worldbuilding and experience designs.

Every time we walk into a building, we become what it encourages us to. When we walk into a temple, we might be a worshipper or a priest. When we enter a hospital, we could be a doctor or a patient.

“I started to understand that houses were more about the narrative people were trying to tell and how they wanted to be understood than about shelter.”

Abraham Burickson

When he founded Odyssey Works in 2001, Burickson and his team would study subjects for up to six months, immersing themselves in everything about their lives, from reading their favourite books to meeting their parents. They would then create an experience for that person, emergent from the questions that arose from the time spent with them – invading their homes and towns, transforming public spaces into specific narratives and creating quiet moments of reflection.

These one-person projects became a kind of lab for understanding the structures of designing experiences, and the importance of an open mindset. For example, when visiting Meow Wolf recently with his four-year-old son, Burickson was reminded of the importance of keeping a childlike sense of awe, wonder and openness rather than cynicism in order to enable the power of experience design to effect greater change.

Odyssey Works’ manifesto is: “All designs are experiences. All we have are experiences.” This focus on the experiential rather than the material dimension of our designs requires a higher level of craftsmanship.

The phrase “Be the change you wish to see in the world” is commonly associated with Gandhi, but in fact its origins are unclear. Gandhi’s actual statement, “We but mirror the world”, is more in line with Burickson’s belief that experience design isn’t only about shaping the external world, but about shaping the self.

“Consider a notion of worldbuilding as one that includes the building of the self: when we build a world, we design who we are. This is a powerful way of considering our role as experience designers.”

Abraham Burickson

Three Experience Design Principles For Real Change

Burickson’s book outlines 10 principles, but he believes the three below draw a throughline that can be used to guide your experience design to new heights. (For the full 10 Principles, WXO Members can join the Campfire Conversation for this Campfire HERE.)

- All we have are experiences.

This belief marks a switch from a “thing-based” mode of making to an “experience-based” mode of making.

In a thing-based mode of making, a banker makes money, or a sculptor makes a vase.

In an experience-based mode of making, you should instead start by defining the intended experience – for example, an experience about the beauty of the natural world. You can then ask, what is the content and form that will lead me there? What narrative and aesthetic qualities will lead to that experience?

- Experiences are framed.

A frame generates a specific mode of looking and attention. Frames can shape our perceptions, behaviors, and even our sense of self within a given context. Designers have the power to create frames that guide how people interact with and understand the world around them.

This is what differentiates between a child’s scrawled drawing and abstract expressionism. Take a urinal, for example. In a bathroom, we experience it in one way. But in an art gallery, as per Marcel Duchamp’s famous piece, it becomes a “Fountain” and a piece of art. When we change the frame, we move into a different mode of seeing and attention.

The frame might be the most important thing we design. So ask yourself: what experience do I want people to have within this mode of looking?

- We live in many worlds.

Many artists and designers are drawn to worldbuilding as an exciting practice, as it allows us to step out of our own normality and exist in a different way. A world is recognised by its aesthetic, the people that inhabit it, and the core ethical basis.

We might immediately think of fictional worlds that are markedly different to our own, like that of Westworld or Star Wars. However, we exist within many worlds within the space of our own. A college campus is a world where you can assume a population of students and teachers, and where you can decide who you want to be when you step inside it. In an airport, your options as to who you might be are quite limited to a traveller or someone who works there, which informs your behaviour, attention, and the experience you might have once inside.

Arcosanti, the experimental city designed by architect Paolo Soleri, is an example of worldbuilding. Soleri’s goal was to design a city in a way that would lead to enlightenment. However, while Arcosanti looks impressive, whether it achieves enlightenment is uncertain and remains a subject of exploration.

What is a world? In a thing-based, objective mode of thinking, it’s everything. But in an experience-based, subjective mode of thinking, a world is the totality of one’s context, and therefore a mode of transformative design.

The Four Elements Of Worldbuilding

When we engage in worldbuilding, we must consider four main elements.

- Place and physics

This includes not only your location and physical environment, but also the subjective physics of your world: how people may move through space, effect change, and perceive things. An elevator, for example, generates the subjective experience of being in a skyscraper, characterised as it is by jump cuts between discrete spaces and floors. An escalator, on the other hand, suggests the single, continuous experience of being in a shopping mall.

When you pass through the tomb of a Sufi saint, you accumulate “baraka”, a supernatural material that attaches to you and may affect you – or not. And Zuccotti Park in New York City was once a sterile, corporate space where people ate lunch or passed through – but once it became the site of Occupy Wall Street, it became an exercise in worldbuilding that changed the physics of the space into somewhere that built community.

- Aesthetics and material culture

These denote the look and feel of our world; both the visual elements and the sensory experiences we might have within it, but also what they represent. We might be fascinated by the rich imagery of fantastical fictional worlds, but what excites us the most is what these images imply: a way of living differently.

A medical wristband implies a sense of structured control that makes us feel safe and understood – an example of worldbuilding for good. But a number tattoo on the arm might make us feel dehumanised and monitored – an example of evil worldbuilding.

- Population and language

The world determines the people in it. When you enter a courtroom, you become part of the population of that world and must occupy one of the positions in it: judge, jury, defendant, lawyer, etc. If you don’t conform, you’re kicked out or you become an outsider. This is why we love role play: it allows us to step into a world and imaginatively become a different person.

“Imagination is transformative. In zones of imagination a certain something is set free. It lets us reexamine our lives through the lens of a different way of being.”

Abraham Burickson

In this way of thinking, Dungeons & Dragons can be as transformative as a social revolution: both question what it takes to change the social rules. The establishment of social rules and norms, even in everyday life, involves a continuous process of world-building. Simple actions like deciding whether someone can wear their shoes indoors exemplifies how social rules shape our environments.

Language is another tool used in worldbuilding that determines the way we engage conceptually with our world. Take the use of the “they/them” pronouns to describe non-binary people: a tiny but powerful experiment that has been brought into the common language to huge reaction and effects.

- History and myth

Worldbuilding often involves reimagining origin stories. These are how we remember our past and what we measure our present against, so when we try to rethink them, there is often pushback – take reactions in the US to the rethinking of the narrative of slavery.

These narratives can be expressed through different ways – the windows of a Catholic Church tell a story, but so does the form of the cathedral, as it’s an encoding of the shape of the world. Origin stories are also filled with supernatural people who have powers beyond the ordinary, whether that’s Che Guevara in Cuba or the Founding Fathers of the United States, blessed with a prescience ordinary people lack.

It doesn’t matter whether these origin stories are religious or nationalistic, true or false: they begin with a supernatural occurrence that gives existence to that world, and asks us how we’re living in relation to it.

If you wield these elements of worldbuilding effectively, you can change the world. Gandhi’s life can be seen as an example of worldbuilding in action: he was one thing when he lived in London, but when he returned to India and engaged in activities like wearing woven clothes and making their own salt, he presented another way of being in the population that helped to bring down British colonial rule. This is also possible within the scale of an app, like the game 80 Days, which offers players a decolonized world-building experience, encouraging players to imagine alternative worlds.

The WXO Take-Out

Burickson’s work encourages us to consider the power of worldbuilding in shaping societies, identities, and narratives, ultimately challenging us to think creatively about the worlds we inhabit and the worlds we can create when we design our experiences.

So next time you’re designing an experience, ask yourself:

- What experience do I want to create? What content and form will lead me there?

- How will I frame this experience? What mode of attention do I want people to see through?

- What are the subjective physics of my experience?

- What are the aesthetics and material culture of my experience?

- What is the origin story of the world I’m building?

- What are the social rules – and how might I change them?

Want to come to live Campfires and join fellow expert experience creators from 39+ different countries as we lead the Experience Revolution forward? Find out more here.