Living Story is a creative company and one of the oldest serious game studios in the Netherlands. Based on 18 years of experience, they design, manage and produce Game-Based Learning solutions from start to finish. This may be events, serious games, Escape Rooms, or “experiences” of any kind. Their weapon of choice is always games.

Here Founder Michiel van Eunen explains how to design awesome learning experiences using Living Story’s methodology: The Game-based Learning Design Wheel. We believe these experience-based ideas are highly transferable, and that you should be able to take what they discovered in their sector, and apply it in your area of the Experience Economy.

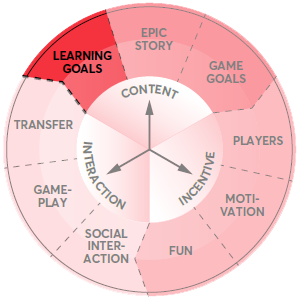

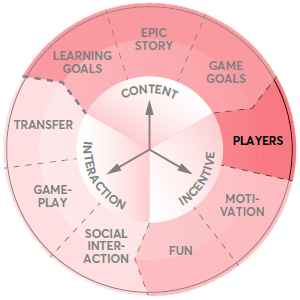

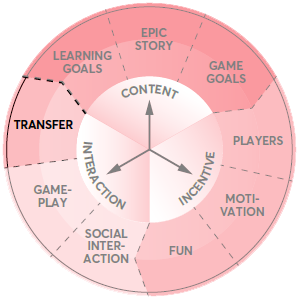

The Learning Design Wheel combines scientific principles of learning theories, game design and theories of motivation and behaviour with our own experience at Living Story. In 2022 we even wrote a book about it: Spelen Werkt. (Playing Works), which is currently nominated as Management Book of the Year and with an English version scheduled for late 2023.

Recently we were commissioned by Traineroo to develop a tailor-made escape game for the top 100 international leaders of a multinational company. In this case study, we explain how we did just that using our design strategy, the Game-based Learning Design Wheel.

Phase 1: Learning Goals

We always design from Learning Goals: what does the client want to achieve in terms of behaviour, awareness, improvements, and innovations of actions?

In this case, the learning objective was clear: where can we improve when it comes to Accountability, Collaboration and Empowerment?

As everything can be an a useful trigger for experience design, we scribbled down the acronym of these values: ACE.

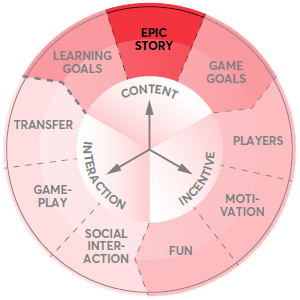

Phase 2: Epic Story

The location we had available was the Blazin’ M Ranch in Arizona, USA, where an old “frontier town” was recreated: a typical “Wild West” town with a bank, hardware store, saloon, jail and everything you can imagine when you think of a Wild West town in the late 1800s.

When developing a game for a live event, you can never deny these two things:

- The players

- The location

Luckily, The Wild West is a great theme for a game, so it was evident what the staging of this game would be.

It was also practical to divide the 100 people into teams of 6. Working in teams is always nice in games, and it offers the opportunity to work together (or not).

Based on these factors (learning objectives + frameworks + theme), we were able to get started with phases 2 and 3 from our Game-Based-Learning Design Wheel: Epic Story and Game Goals.

When you think of the Wild West, you think of outlaws like “Billie the Kid”. Bandits on “Wanted” posters hang in dusty towns hang because they’re wanted for robberies of stagecoaches, saloons and banks.

With this we immediately had a nice ingredient for the game. We had previously used a deduction game with criminals for De Buit (The Loot), a game in an abandoned prison, and with Cold Case: The Diamond Heist, an online escape game we made during the Covid pandemic.

This became the Epic Story:

150 years ago, a gang of bandits plundered 15 towns in the area. It went on for months and all sorts of goods were stolen. At some point, the robberies suddenly stopped. The bandits were never heard from again, and the loot was never found.

Representatives from the 15 towns gathered at Pinnacle Peak, presenting witness statements, newspapers and other matters pertinent to the robberies. Unfortunately, they did not manage to put the pieces together and discover who the bandits were and where they might have hidden the loot.

Today, 150 years later, the Statute of Limitation expires, meaning that investigation into one of the Wild West’s greatest heists has come to an end. Today is the last chance to discover the hidden loot!

What we have at our disposal:

- The 15 casefiles of the plundered cities

- Robin Bush, a local historian (accessible via chat, a smart chatbot)

- Sheriff Bucky O’Neill, standing by to take action (on-the-spot video in the desert)

- People who work at the Ranch today and who know a lot about its history, such as Rosie (Saloon Owner), Jim Pedler (handyman – his great-grandfather owned a hardware store that was raided by the gang), and Red Garter (photographer). These were live actors from whom players could purchase information

- The 100 players

- A budget of 10 gold pieces per team to be spent on “research”

- 1-hour time window

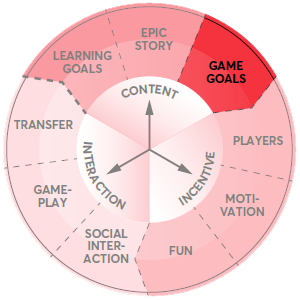

Phase 3: Game Goals

The primary game objective: find out the specific location where the gang has hidden their stolen goods.

All teams have a map of the area and a search warrant. They must hand it in at the end of the hour. The more specific the description, the better. We built in this nuance to be able to select a winner from multiple “correct” answers.

Phase 4: Players

We knew that the players had different cultural backgrounds. There were people from the Netherlands, USA, and Asia. The teams would be composed in such a way that each team would reflect those different backgrounds.

Only a small portion would be familiar with games like this. They were also leaders: people who are used to directing others, and not always the people who roll up their sleeves. The group was relatively old (40+), experienced, loyal, mainly men, and with a technical background.

The players participated in a two-day session. This game is one part of the first day in the afternoon. In the morning they have already had an intensive program, both physically and mentally). These were all things to take into account when designing the gameplay.

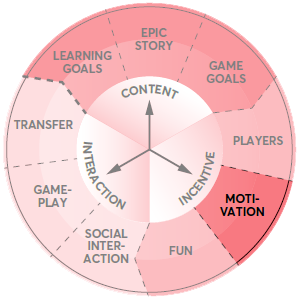

Phase 5: Motivation

The fantastic location, epic story and game goals are all ingredients that contribute greatly to the fun of the game. Another ingredient is the game materials: a large treasure map for each team (A0), an old case file, 32 Wanted posters in the village, and a specially designed map tool.

Beautiful, well-kept, high-quality game materials ensure that players are motivated to start playing. Game designer Jesse Schell calls this “The Lens of the Toy: Do players want to play your game, even if they don’t know the rules?”.

Phase 6: Fun

The actors have been briefed to adopt a flexible attitude when it comes to pricing their information. For example, Jim Pedler can sell his ‘Maptool’ (an old tool you need to read the map) for 5 gold coins, but also for 4 if you happen to be the first team of the day, or for 6 if business is very good and demand is getting higher. (Or if you are too brazen as a team or try to bribe Jim!)

This interaction with actors, thrill of spending money and negotiating with other teams contribute a lot to the strongest motivators in any game: Relatedness, Autonomy, Mastery and Purpose.

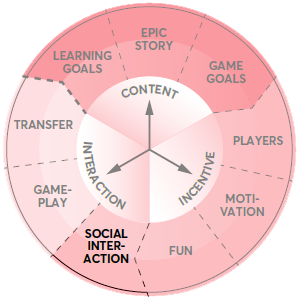

Phase 7: Social Interaction

We used live actors where you could get, or rather buy, information. Each team has a budget of 10 gold coins. (Note: these are also ‘real’ coins; We once minted 2500 brass Living Story coins, which we have used for various games for years. This is also a conscious design choice: the physical feel of a pouch of coins is different from that of plastic carnival coins).

The economy of the game is balanced in such a way that you don’t have enough money to buy all the information from the actors within just your own team.

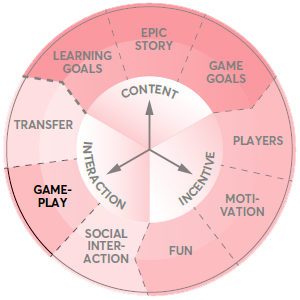

Phase 8: Gameplay

Players were welcomed by Blazin’M, the ranch owner. He tells them about the marauding gangs and orders them to come up with the exact location of the stolen good within the next hour. The teams receive the materials (files, map, money) and can start immediately.

Among other things, they have to find out which 4 bandits were part of the gang that robbed the 15 villages in 1872. For this they have to look for Wanted posters that hang throughout the village. Each contains a name, a photo, various characteristics and a reward offered.

In addition, they can go to Rosie in the saloon – she seems to know old cowboy songs that tell about events in the Wild West…

They can also spend their money on buying a ‘map tool’ from Jim Pelder, or have their picture taken at Red Garter, the only way to gain access to the dark building Red uses for his photography, and where one of the robbers would have left his name.

Through a combination of good searching, smart combining, deducing, collaborating, negotiating, weighing interests and taking action, teams can find an exact location on the map. Teams that pay close attention – or think a little outside the box – can pick up extra information along the way, which allows them to collect even more specific information about the final location.

Phase 9: Transfer

At the end of the game, all teams hand in their search warrant. In this case, 6 of the 15 teams had the correct answer. This is an ideal result for the intended purpose – and an outcome designed that way. If all teams had the correct answer, they would feel little need for critical reflection: after all, they all did a fantastic job. If none of the teams won, then the game is just worthless, and it is certainly not the fault of the players.

If 6 of the teams have the correct answer, it means that you could have won the game if you had done the right things: after all, each team played under exactly the same conditions and with the same materials. That also means that the difference between winning and losing teams is in the way those teams played.

In the reflection immediately after the game, we looked back at the behaviour of teams during the game. Why were which choices made? And by whom? With the Transfer we also always look specifically at the learning objectives, in this case Accountability, Collaboration and Empowerment.

We also used a gamification element: each player received their own deck of playing cards. They could score their own behaviour by placing a numbered playing card (2 to 10) face down on three posters with the fields Accountability, Collaboration and Empowerment, where 2 was a low score and 10 was excellent. Picture cards were not allowed, and nor was – to the regret of some teams – the Joker card. Cards were then turned over, scores compared and a substantive discussion followed about the difference in scores, the interpretation of the values and the terms, the distance between the actual and the desired behaviour, and the parallels and relevance in daily practice.

For more case studies and learning frameworks from the Experience Economy, check our Case Studies page here.