If the pandemic proved anything, it’s that we’re all irreversibly connected. We’ve been living in an increasingly global society for some time – but with remote working, virtual communities and digital entertainment all exploding in the last 18 months, the physical boundaries that keep us apart seem less constraining than ever.

So what does this mean for experience designers? If your audience is online, are they always global? When you’re designing for an IRL experience – whether you’re in Las Vegas, Paris, Dubai or Hong Kong – who are you designing for? International visitors? The locals? Perhaps the locals are from somewhere else anyway, or several somewhere elses. Should that impact how you design? And if so, how?

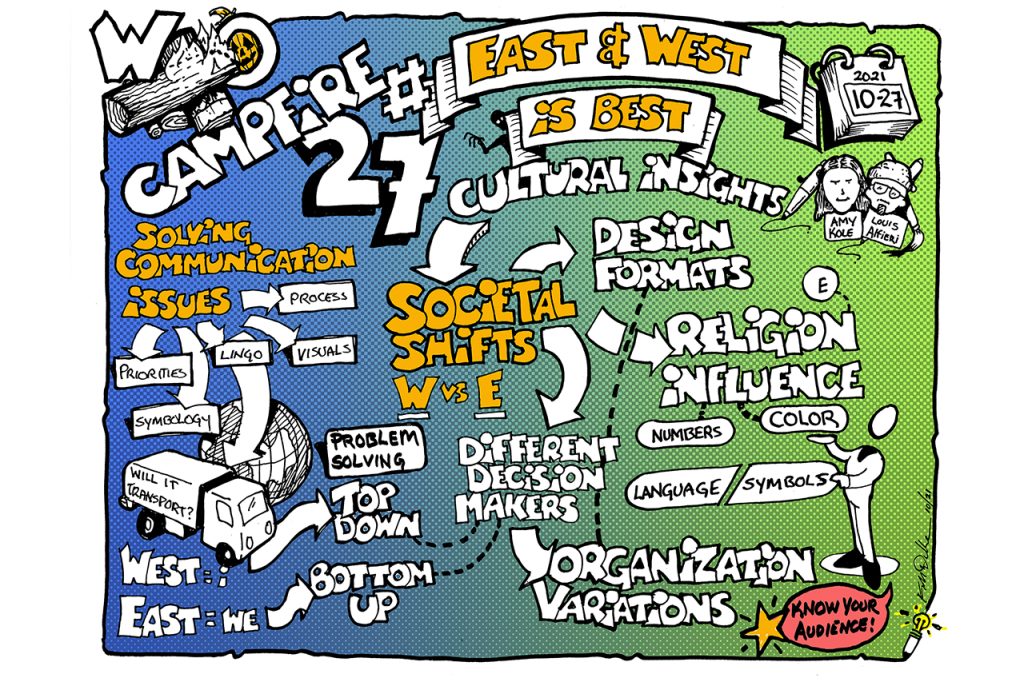

To untangle these questions, both fascinating and ever more relevant in our connected world, we invited Louis Alfieri and Amy Kole to present their ideas in a Firestarter talk on the topic “East And West Is Best: How To Use Cultural Insights To Expand Our Creativity & Build Better Experiences For Today’s Global Audience”.

Having started out as a sculptor and illustrator, Alfieri has now been an experience designer for 30 years, working across the globe but with an emphasis on Asia and large-scale mixed-use developments, entertainment destinations, theme parks, brands, and cultural projects.

He started the transformational experience company Raven Sun Creative in 2011. Narrative writer Amy Kole is one of the global experience experts Raven Sun works with. She has worked on themed attractions for Universal Studios Japan and is now based in Florida, where she writes mobile game scripts, does high-level concept development for theme park attractions, and generates informative content for clients such as Honda and Instacart.

Before the Campfire, participants were asked to consider:

- What cultural experiences and interactions have you had that have influenced how you develop and create content for your audience?

- Have you lived or worked internationally, and what was your biggest personal moment of illumination from that experience?

- What cultural experiences touched you that you want to share with the group?

- What can you adopt and adapt from that experience that will create more meaningful experiences for the global audience?

Here are a few of the answers they shared.

Whizz Bang, Can’t Concentrate, Man

Lighting designer Koert Vermuelen shared a cultural difference he’d noticed while working on shows in China and the Middle East: a much shortened attention span.

“If the men in the Chinese audience weren’t captured for 15 seconds, they were already on their phones scrolling. I saw the same in the Middle East. In Europe, it’s still a mark of respect that when you come into a theater, you put your phone on silent or put it away.”

Koert Vermuelen, lighting designer

We might be in an attention economy, but what happens when our average concentration is vastly different between demographics? In this case, Vermuelen realised that the solution was to provide regular attention-grabbing moments to keep audiences engaged.

“Every two minutes you had to give them something to keep them captured. It really influenced the design I did for a future show, which I exploded by two or three times with lighting and special effects compared to what I would have done for a European show.”

Koert Vermuelen, lighting designer

A Common Language For Uncommon People

Visual thinkologist Kevin Dulle insisted on the importance of a common language to aid communication.

“You bring your own inherent thinking, not realising that there might be different ways of communicating. A good example we were presented with in Asia is the idea of priorities: what they think is important may be different to how you function.

The use of lingo is also important. What you say may mean something completely different to someone else. So it’s always best to get your ground rules down first.”

Kevin Dulle, visual thinkologist

(For more on the importance of a common language – and tips on how to create one – check out Campfire 23: How To Bring Different Worlds Together. Dulle is also working with experience design professor Bob Rossman on a common language dictionary for the Experience Economy, which we’ll be bringing you more on soon.)

Experience producer Heather Gallagher suggested another solution to the challenge of communication: where verbal communication might fail, a picture’s worth 1,000 words. Plus, there’s something even better that unites us: emotion.

“Art, imagery and visual communication transcend language. The other thing is that you can still have a shared emotional experience. There are only so many basic human dramas and narratives. There’s revenge, there’s love. If you keep it light on narrative and get people into those basic stories they’re familiar with, that is universal.”

Heather Gallagher, experience producer

(For more on the idea of basic stories and narratives, watch out for our upcoming Campfire with cognitive and evolutionary psychologist Manvir Singh.)

Visual communication alone does have its limitations, however. Experience strategist Arjan Schimmel pointed out that different cultures can also experience visuals differently, in the same way as they do words.

“Words can have a different meaning in different places – a Brit can experience the word ‘interesting’ very differently to an American. But people also see things through a different lens.

I worked with Philips in Europe to make its packaging look very stylish by giving it quite simple colours and tones. But in Asia that was considered cheap-looking; it has to have bright colors to give a luxurious feel, which in Europe might be considered garish. So it’s always good to test things with people from different cultures before you actually put them in experiences.”

Arjan Schimmel, experience strategist

This is why design trends are so important, according to interior and experiential designer Vanine Narjaryan.

“You need to understand the trends, not the transcendental.”

Vanine Narjaryan, interior & experiential designer

Experience Design: The Next Great Art Form

Alfieri began the Firestarter by playing a Bruce Lee video underscoring the need for “emotional punch” in an experience. As Lee says, “Think, don’t feel”.

Whatever culture we come from, there are similarities between us as human beings. So we should look for “species-level patterns of behaviour” that transcend cultural barriers.

For Alfieri, experience design is the art of discerning these universal languages – and that’s why it needs to be taken as seriously as other art forms, like photography or architecture.

“There’s an element of magic to what we do as experience creators. We use storytelling to transcend communication and be transformed as individuals. Music and culture are both universal languages of mankind that we use to communicate what we do.

Experience design isn’t yet as well recognised as photography or architecture, but my hope is that we as a group are helping to build that art form to gain that kind of recognition around the world.”

Louis Alfieri, experience designer

East Vs West: The Fundamental Differences

Using Yang Liu’s book East Meets West as a baseline, Alfieri illuminated some of the key differences between Western and Eastern culture, from how we solve problems and network to the way that confrontation is avoided at all costs in Eastern cultures.

The Seven Samurai vs The Magnificent Seven

One of the most obvious differences between Western and Eastern cultures is the preference for individualism in the former and collectivism in the latter. And perhaps the perfect example of this is in comparing the movies The Seven Samurai and The Magnificent Seven.

Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa made The Seven Samurai in 1954, which later inspired many Western movies including Star Wars and, you guessed it, 1960’s The Magnificent Seven. But where in the Hollywood version they are individuals, in Kurosawa’s telling they see themselves as an integral part of the town they decide to defend.

“In The Seven Samurai, the villagers seek protection and participation from the samurai, who are of a different class. However, they see themselves as having a social responsibility to help the community out.

In The Magnificent Seven, you have seven individuals who for various reasons make sacrifices ability to help the town, but they never see themselves as a collective part of it. They see themselves as individual mercenaries that are each dealing with their own individual problem within the context of the story.”

Louis Alfieri, experience designer

Kishotenketsu Vs The Hero’s Journey

In Western culture, much of our understanding of storytelling comes from the Greek three-act structure and The Hero’s Journey, as articulated by Joseph Campbell. From Hollywood movies to written books, this origin story is the one that dominates the way we tell stories.

Conversely, if we look at Kishotenketsu, a Japanese storytelling structure most commonly associated with Eastern stories, it’s a four-act structure that has a different ascent and function.

The differences between these modes of storytelling mean that Western and Eastern audiences are accustomed to different things. In Western culture, we’re accustomed to a happy ending – but in Asia, the end of a story is often sad or challenging. This represents an opportunity to create different types of projects, but it’s also a challenge.

“If you’re a Westerner crafting stories in another culture, should you adapt your storytelling to enrich your narrative opportunities? In Asia you’re not limited to ending on a happy note; you can create a ride, attraction, experience or show that ends in a way that you would never be allowed to do in the US or Europe.”

Louis Alfieri, experience designer

Alfieri added that while there may be different ways to articulate the peaks in your narrative, the peak-end rule is still relevant across cultures. Ultimately, we’re taking people on the same journey, wherever they’re from.

“As experience designers we’re engaging the consumer in a journey. They are coming to us and being transformed as a part of our experience and exiting that in a different frame of mind. We enter the experience as who we are. And often we leave it as who we want to be.”

Louis Alfieri, experience designer

Communities Vs Nuclear Families

Cultural differences don’t only apply to the way we think, but to the way our audience is structured. If we think in numbers, in the West we typically design experiences around two to four people, a standard nuclear family unit.

But in the East, and particularly China, three is the fundamental family unit, increasing to seven if you include two sets of grandparents. In the East people are also likely to travel in larger family or community groups, so you might be looking at a number closer to 20, or even 60.

“So you’re looking at jumping from seven people to 20 or 60 people that you’re organising a story for. Not only does this affect us creatively in terms of narrative structure, but spatially how does that relationship work when you are creating a moving system, or a seating pattern?”

Louis Alfieri, experience designer

Queues Vs Chaos

Even something as seemingly unrelated as population density can have an effect on consumer behaviour and how we design experiences.

If we compare Japan, China and the United States, Japan by gross land area is about the same size as California. However only 25% of that land is habitable – yet Japan has two thirds of the population of the United States living in it.

China is roughly the same size as the United States, but has four times the number of people. New York and Los Angeles are the only cities in the US that have over 10 million people – but Tokyo has roughly 24 million, and in the future Beijing and Shanghai will have 70 million.

Alfieri explained how these differences affect behaviour.

“The influence is things that we wouldn’t necessarily think about, such as why people queue a certain way. How they organize spatially. How sound is attenuated. Because of the incredible density in a very small area, the Japanese are very structured and organised as a community. Your intent is to not affect others; you do not want confrontation.”

Louis Alfieri, experience designer

Alfieri gave an example of his and Kole’s work on a Christmas tree in Universal Studios Japan back in 2006.

“There was a three-hour line to stand up and take a picture of the Christmas tree that went in a circle around the entire theme park. There was one person at the end of that line with a little sign that said ‘end of the line’. There was no queue line, no rope, no tape, no anything. All of these tens of thousands of people lined up for three hours to stand and get one picture in front of a Christmas tree. It’s unheard of in the United States. It would be mayhem.”

Louis Alfieri, experience designer

The way these large numbers move is also significant, with festivals forming the equivalent of great human migrations. Take China’s Spring Festival, for example, the largest migration of humans on the planet.

“More than 400 million people travel from the cities out to the rural areas to see their family at the same time. So we’re looking at mass volumes and locations where people are going to have experiences in sheer, incredible numbers and transportation that dwarf anything people understand in the West.”

Louis Alfieri, experience designer

It’s All About The Numbers

Numerology and auspicious days also play a huge role in Eastern cultures. In Western culture, 13 or 666 are perhaps the two numbers we bristle at – but in Eastern numerology, numbers have great significance on a daily basis. Four is associated with death, eight with wealth and fortune, and nine with permanence, for example.

“Every time we release an idea or innovation on our website in China, we consult with an auspicious days company to identify what numbers we should use.”

Louis Alfieri, experience designer

Kole gave a few examples of how this might work while organising real-life experiences.

“If you’re designing a Halloween event in Japan and you suggest using the number four, you’ll get a bad reaction. You don’t want to invite something negative, whereas designing a Halloween event in America, you’ll see 13s and 666s everywhere. There is less of this stigma behind what these numbers mean.

You don’t realise it as a Westerner, but in the East these numerical messages are everywhere. And they’re throughout history. So when you think about the number nine, you don’t realise that when you go to the Forbidden City that color and number are present on every building, sending messages to the entire community. The number nine is about permanence and duration, so all of the doors in the Forbidden City are multiples of nine.

Those levels of significance are throughout Asian history and culture, so our opportunity when we’re designing experiences is to take those lessons and apply them to whatever we’re doing.”

Amy Kole, narrative writer

Educating Experiential Consumers

Sometimes, culture clashes can lead to awkwardness – take etiquette issues around bathroom culture, for example. Westerners might not be used to floor toilets, and people coming from rural areas of Asia might not have seen a toilet facility before.

Disney World dealt with the issue of people going to the bathroom in their parks by coming up with the idea of being a “star guest”, educating people about how they should behave without confronting or embarrassing them.

All of our customers are different. So we need to design so that whatever their level of sophistication, they can learn the rules and operate with no awkwardness.

The Best Of East Meets West Co-Creations

At The WXO, we’re really interested in what we can achieve through co-creation – our CEO James Wallman and immervive Van Gogh experience creator Arnold Van Der Water and Alfieri recently spoke about this in Barcelona at IAAPA.

So, with all of this in mind, what are some actual examples of brands and projects doing East-West co-creation really well and connecting on a creative and visual level?

- Minecraft: a gaming experience where players from the East and West join together on creative development online and in real time.

- TikTok: a social media platform that originated in the East and has been embraced and is in rapidly expanding in the West.

- The Museum of Other Realities: a VR museum where creators in the East and West create exhibits and interactions in real time, online. (Best viewed via your favourite VR headset, of course.)

- TeamLab and Sketch Aquarium: TeamLab is a Japanese art collective that has been developing a range of incredible experiences that they’re now exporting all over the world. Superblue in Miami was created by them, and they’ve been instrumental in creating a non-linear art immersion experience called Sketch Aquarium that is non-narrative based, where you can interact around the world and in real time.

- Lionsgate’s Dorian: Lionsgate has just announced the ability to open the Dorian storytelling platform to create completely user-generated content (UGC). This is an opportunity where Lionsgate is allowing their brand to allow anyone in the world to create a game experience or narrative through their IP on this platform, but which they have no control of.

- Ocean Flower Island: Alfieri was the executive consultant for the Ocean Flower project, a very large-scale mixed-use integrated project about four times the size of the Dubai Palm. It’s on the north shore of Hainan Island, and consists of 25,000 residential units, 18 museums, three theme parks, and 24 resort areas, all meant to be a global destination for all people that are participating in coming and engaging across all narratives.

- Nike: Nike is a brand that has really understood its ability to communicate as a platform with the world. Nike doesn’t tell you they’re making shoes and t-shirts. They are a platform for you to create the greatest sense of yourself. And that is a universal archetype that touches people all around the world. Alfieri gave an example of a running track where you compete with yourself, based in the Philippines.

- Dubai: one of the greatest examples of multicultural storytelling and brand development that’s ever been articulated in history. You have a country that in 1990 was virtually empty and in 2018 is one of the leading destinations in the world, centered between the East and West. They’ve taken a conservative Muslim nation and created an oasis for Muslim people to feel free and comfortable, and also for Westerners to come join the experience too. They’ve reconceived the notion of the city state as a global lifestyle and aspirational brand.

- Moment Factory: a multimedia studio that has been delivering a number of experiential installations around the world.

- Burning Man: a festival that is now located in more than 15 countries and has a digital version of itself that’s available around the world.

- Puy du Fou: a theme park that has now expanded as an experiential destination beyond France. They’re in Spain and are opening in China, the US and South America shortly.

- Van Gogh – The Immersive Experience: a travelling immersive art exhibit that many other museums are now looking to as they start to integrate culture into what they do, both IRL and digitally.

Less think, more feel

Alfieri’s final call to action – recalling the Bruce Lee scene we saw at the beginning – was for ”less think, more feel”.

“We have the ability to make a difference in the world. We want people to have a good time. We want things to be less think and more feel.”

Louis Alfieri, experience designer

The Sparks

After Alfieri and Kole’s presentation concluded, our Campfire had the chance to share some of their own thoughts.

Director Tom Vannucci added that people are not only different in different countries or continents, but in different cities, towns and states. He gave the example of working in Tennessee, where more “whizz bangs” were needed than for a New York or LA audience.

“I did a project in Pigeon Forge, Tennessee. Those of us who came up through Disney or Universal followed the template of creating a show product that’s about 20-35 minutes long, because it’s all about seeing how many people we can get through. But in Tennessee that was wrong, because their value proposition is the longer the show, the more value they’re getting for their dollar.

Our challenge is, how do we respect those cultural differences, but still do what we do?”

Tom Vannucci, director

Sai Aditya agreed that we have to educate experiential consumers, whoever and wherever they are.

“As experience designers, we have these blind spots. As a designer and a creative person, you might be really fuelled up about something – there’s going to be gamification! There’s going to be transmedia! – and you suddenly realise that the other person is eating all of this for the first time. And I think the point is to drip-feed it slowly and train the audience.”

Sai Aditya

WXO Founder James Wallman was reminded of our discussion back in Campfire 7: Is It Possible To Design For Transformation?, where we talked about guiding people into an experience.

Vermeulen and Vannucci both pointed out that however much you try to accommodate local tastes, it’s important to stay true to what your vision.

“We must give ourselves permission to be the experts, otherwise they wouldn’t hire us.”

Tom Vannucci, director

Still, as he highlighted, there’s a difference between design and art. Design is a functional tool, and art is a vocabulary.

“It’s your art, or your vocabulary, that you’re going to bring to the design process. But sometimes we just need a really good interpreter. And that interpreter for the vocabulary is where we get challenged – and we have to, because sometimes our vocabulary doesn’t translate. So then how do we come back with different vocabulary to still maintain the creative intent to keep our art?”

Tom Vannucci, director

Whatever the challenges, however, designing for and communicating with a global audience can work. As Wallman said, look at Netflix and the way it’s turned local productions into global phenomena: Spain’s Money Heist, France’s Lupin, and South Korea’s Squid Game.

The WXO Take-Out

Even though they might be challenging to think about, cultural differences can also be a stimulus for creativity – and an opportunity to do things differently, or in a way you might never have been allowed to in a different cultural context. And in an increasingly digital world where digital means global, you don’t have the luxury of ignoring them.

So when designing an experience, ask yourself:

- Why does my experience have to finish this way?

- What are the other possible narrative endings?

- How might I design differently for different demographic groups?

- How might I design for peak periods?

- What alternative meanings in verbal and visual language might I be missing? How can I both avoid (if negative) and use (if positive) these?

- How do I balance designing for the needs of the audience with maintaining the integrity of my art form?

And if you’re struggling with these questions, or working in a city or country or with a company or audience that you don’t know so well, the WXO can help you to create an experiential support group. Let us know, and we’ll find another WXO Co-Founder or Founding Member who has worked there and can help you figure it out. Contact us for more details.

Interested in taking part in discussions about experiences and the Experience Economy? Apply to become a member of the WXO here – to come to Campfires, become a better experience designer, and be listed in the WXO Black Book.