What might you see if you experienced life with your eyes wide shut?

We’re very excited about the potential of “functional experiences”: those that use sensory stimulation – or deprivation – to access dream, hypnagogic or even psychedelic states.

By doing so, they might help us to rewire our minds and emerge as stronger, better people: the ultimate realisation of what Joe Pine calls the transformation economy, or “New You” business.

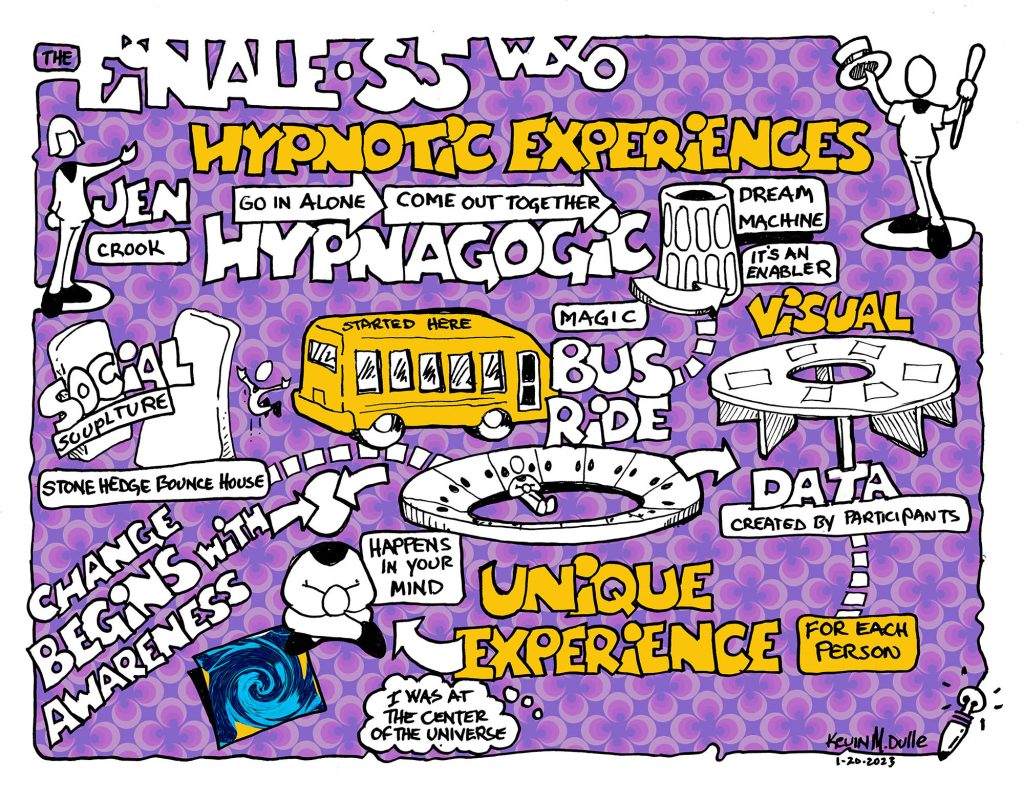

The “eyes-closed experience” is one branch of functional experience that plays with sensory stimulation and deprivation all at once. So for our Season 5 finale, we welcomed an absolute firecracker of a Campfire examining a groundbreaking eyes-closed experience that’s also an ongoing experiment into the very nature of perception…

Jennifer Crook is the Director of Collective Art, the creators of Dreamachine: an immersive eyes-closed artwork which blends neuroscience, architecture, music and technology to explore the mysteries of consciousness in what could be the most remarkable social project of its kind. Participants enter a specially designed circular room and have white light shone into their closed eyes to a soundtrack by musician Jon Hopkins, inducing intense visual hallucinations.

Collective Art’s focus is to create meaningful, shared experiences that are completely collaborative – between their team, but also with their audiences. Crook’s particular experience in producing major participatory pieces – including turning London’s Piccadilly Circus into an actual circus, making a lifesize bouncy replica of Stonehenge with artist Jeremy Deller, and transporting 210 tonnes of Ice to the streets of London with artist Olafur Eliasson – centres around creating a new experience that invites audiences into something they wouldn’t usually witness.

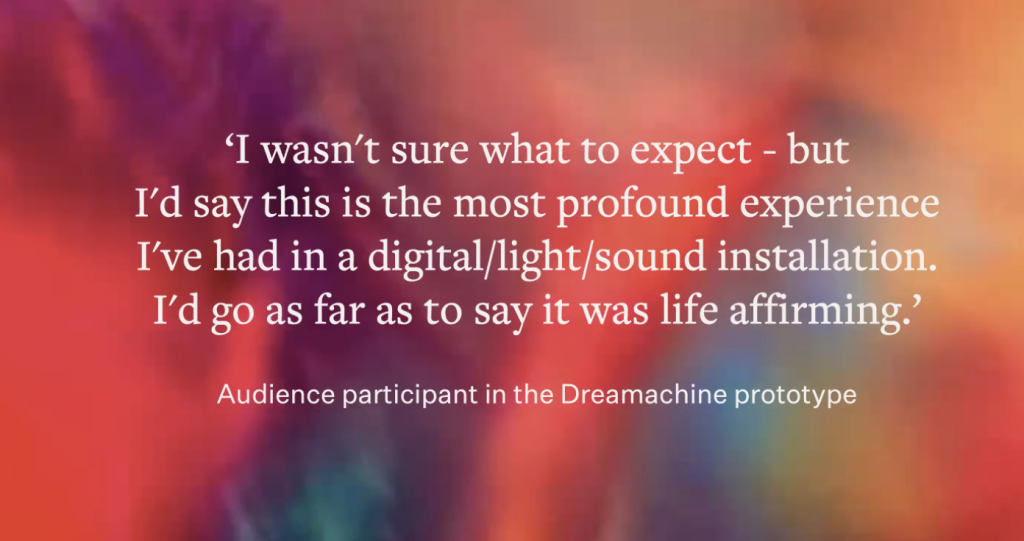

Dreamachine certainly falls into this category, with those who have experienced it describing it as both “a relaxing escape from the everyday” and “a meeting of myself at the end of the world”. Partially sighted participants even reported a spectrum of colour they’d previously thought impossible.

The project has also led to a “Perception Census”, the biggest citizen science program looking at perceptual diversity ever undertaken. So far 50,000 participants have taken part to help explorethe mysteries of the mind and the phenomenon of consciousness.

On one of our most revelatory and spark-inducing Campfires yet, Crook took us on a journey through the development of the Dreamachine. We heard about what she learned in the princess about building powerful collective experiences that create a contemporary sense of ritual, blurring the boundaries between science and art, and designing temporary experiences with a lasting impact.

Ready for a trip into the depths of perception?

Beat Poets & Transcendental Beats: The Roots Of The Dreamachine

From the start, Dreamachine was pitched as an interdisciplinary programme of art, science and technology.

“At the beginning we didn’t know where we were going, but the things we learned gave it meaning and impact.”

Jennifer Crook

However, the origins of the Dreamachine stirred all the way back in 1959. Brion Gysin, a Beat generation writer and friend of William Burroughs, fell asleep against a bus window while travelling through Marseilles. As he drifted off, Gysin entered another realm he described as a transcendental space, out of time and place. This “kaleidoscopic world” stopped the minute he opened his eyes.

Gysin initially thought he’d been blessed with a supernatural encounter, only later learning that he’d experienced the neurological effect of light coming through to your brain. Alpha frequency entrains your brain to that frequency, but because it doesn’t know the stimulus, your brain creates an extraordinary response that neuroscientists still can’t explain.

Determined to bring this revelation to the masses, Gysin created the first Dreamachine: a flickering light device made up of a record player and lightbulb designed to be experienced through closed eyes. The gaps in the Dreamachine were cut at the same alpha frequency that creates the effect in the brain, and was designed so that anyone could replicate it. Gysin prophesied that it would replace TV sets in homes everywhere, and died still raving about his discovery.

Forty years later, Crook came across the magazine Flickers of the Dreamachine, while rifling through a charity shop. She cut out the pattern in the back, made her own version, and had the same revelation: how was this possible? She was obsessed with it throughout her teens, but eventually forgot about it.

Years later still in 2014, Crook was at the back of the room for a Jon Hopkins gig in London’s Royal Festival Hall. Hopkins’ music veers from gentle and melodic to full-on transcendental rave and trance. The concert was seated, and for the first half nobody moved. But in the second half, a man stood up and started dancing. Stewards told him not to, but two minutes later he stood up again – and this time, the whole audience in unison began dancing and running to the front.

“It felt like a moment where something collective had happened and energy had been released. I wondered: what had felt so powerful, and how could I experience it again? How could you generate, deepen, and acknowledge that such an experience can happen?”

Jennifer Crook

How Do You Create A Communal Experience?

It was this experience that made Crook realise the untapped potential of the Dreamachine. She decided to take the phenomenon and use it as a basis for a shared experience, moving from an object to a space.

“We wanted to create a communal experience at heart – one of those moments that lifts you out of the everyday and affects the way you think and your emotions.”

Jennifer Crook

When UNBOXED – a festival celebrating creativity in the UK – put out a call for creative ideas from an interdisciplinary team to co-design and create something that involves millions of people in a shared experience, it seemed like the perfect fit.

Crook gathered a collaborative team consisting of the art collective Assemble, the musician Jon Hopkins, neuroscientist Anil Seth from the Centre for Consciousness Science at Sussex University, creative technology studio HOLITION, and several other scientists, philosophers, sound designers and engineers.

Together, they designed their own version of the Dreamachine that toured the UK. The experience took the following form:

- First, participants are welcomed into the space. They are encouraged to leave the outer world behind, with their phones locked away and time built in to settle into the space. The choice of venues for the Dreamachine was also significant – in Belfast, for example, the deconsecrated Carlyle Memorial Church was imbued with a new sense of transcendance.

- Next, the audience enters the Dreamachine, which is set up like a campfire, or secular temple. They are given breathing exercises and time to settle in before they are invited to lose themselves in the “sonic palace” and “technicolour world” of the Dreamachine. On the surface, all that happens is that a white light is shone into their eyes. But what happens on the inside is remarkable.

- Finally, they emerge into a reflection area. This is the moment where people start to connect and come back together. They can participate in a range of activities to deepen and integrate the experience, such as drawing, writing, reading and talking. There is also a data visualisation collating people’s experiences which is played back in this space.

The drawing table was especially popular, gathering over 20,000 contributions – you can view them on the Dreamachine website here. Despite being wildly different, patterns and similarities began to emerge, and two PhD students are currently analysing the results to draw out scientific data they would never have had access to before.

“The Dreamachine explores the parallel track of inner and outer really deeply. The vivid, incredible, colourful world being generated behind your eyes invites some interesting philosophical questions of what it is to see.”

Jennifer Crook

How To Build A Cross-Disciplinary Team

To achieve such a complex and collaborative project, how did Crook assemble the right people?

The team behind the Dreamachine was handpicked and took 7 years to build. It was an unusual offer for people to sign up for something where they had no idea if it was fundable, where it would take them, or if it would even work. Plus, there was the challenge of getting scientists, archaeologists, musicians and designers all speaking the same language. (For more tips on how to do this, check out Campfire 23: How To Bring Different Worlds Together.)

“Subjective experience is what brought all these collaborators together, whether through research or direct experience.”

Jennifer Crook

To make it work, Crook recommends two things:

- Start with a campfire. The Dreamachine prototype was built in the depths of lockdown, with bean bags and gaffa tape, in the basement of Somerset House. At that point not many people had experienced the phenomenon, so it was important to gather collectively and get a glimpse of what was actually possible. Some members of the team felt like they had left their body, giving them the confidence from the get-go that if they could produce that response with such lo-fi materials, what could they do in a year?

- Remove all labels. Everyone’s subjective experience was valid. A big learning from working with an interdisciplinary team who are titans in their field was that no-one is an expert in this specific thing, so they needed not to waste time on definitions and leave their expertise (and ego!) at the door. Scientists had to think like artists, and artists like scientists. Their mission was not to become the show, but to enhance the audience journey, even if that meant hiding tech rather than showcasing it, or being careful that it didn’t feel like a lab experiment.

“The democracy of bringing everyone together is the thing that brought us together. We described ourselves as a weird cult – it felt like we were on a mission.”

Jennifer Crook

Your Audience = Active Citizens

The entire Dreamachine experience is invisible and generated in the minds of the audience. This meant that the team couldn’t see if it was working – they could only bring people in, ask questions, and hope that they were the right ones and that they understood the answers.

As part of this active collaboration with the audience, the Dreamachine team brought people into their prototypes really early on – even before they were ready to. They made five different prototypes of varying scales and developed them with over 2,200 people in extensive focus groups, including those who were blind, deaf, partially sighted, and had conditions like anxiety and ADHD. Some participants claimed to have seen colour for the first time – something they didn’t know was possible previously.

Including such a range of participants led them to develop two different experiences: the primary one and Deep Listening, which is without the flickering lights and has a gentle, ambient lightscape. People had visual experiences without the lights, showing that your senses can work together in really unusual ways in different environments. This reminds us of Beth Rypkema’s work on accessible experience design, in which she teaches that we shouldn’t design for disability afterwards, but allow for it at the beginning and see where it leads us.

To be really committed to the process of participatory design, your audience have to be active citizens rather than witnesses who come in after the effect.

“We told people as little as we could get away with. We brought people in from the nearby park, and wouldn’t say anything about what we were doing! It gave us raw experience with no priming or expectation, so we knew everything they said was genuine.”

Jennifer Crook

By putting every element of the experience through a focus group, it helped the Dreamachine team to understand what people needed to feel safe: a crucial part of gaining their trust. By asking really open and focused questions and taking the audience on the journey with them, they were able to help form a language to speak about the project.

“Every contact leaves a trace. Every aspect of the experience affects the overall integrity.”

Jennifer Crook

All these little touches add up and affect how transformational the experience can be if you get them right. To aid this process the team developed the idea of “the guardian”, borrowed from Burning Man festival: understated spiritual guides who hold the space for people going through different experiences. These people were the anchors before and after audiences emerged from the Dreamachine – “A lighthouse in unfamiliar waters.”

All 92 guardians were trained in disability and mental health awareness. They saw everything: tears of joy and sadness, minds and hearts opened, special and vulnerable moments. Someone could share a profound experience with a stranger in a public space, building a culture of generosity and trust and allowing for reflection between staff and audience. One person in Woolwich came 27 times as it had a profound effect on his mental health. Sussex University is now doing a study into how the Dreamachine might be used as an intervention for mental health conditions.

Leave Space For The Unexpected

Gathering feedback during the prototyping stage informed the design process and “landed what this project could be”. The team created space for the audience to leave reflections beyond what they could design for, inviting people in to share what they wanted to.

“We could design it to within an inch of its life, but everything on the other side was completely out of our control.”

Jennifer Crook

At the start of the project, this was a scary prospect. They couldn’t even describe what the effects of the experiment would be and didn’t have any photographs – so it was quite a gamble to take it to every capital city in the UK. However, the team realised that they needed to lean into this uncertainty.

“The mystery became part of the invitation. The opposite to what we feared happened: it sold out as people heard about it through word of mouth.”

Jennifer Crook

Change Begins With Awareness

When we’re producing temporary experiences like Dreamachine, how can we claim that they lead to permanent change? It’s a challenging thing both to say and to believe.

Crook believes that the kind of insights produced by Dreamachine, where people share their personal experience, have a lot of integrity and really count.

“The quiet, personal and profound to one person can often get lost in the metrics, scale and spectacle. But the small and intimate is something we need to hang on to. It can be transformative.

Gysin’s experience on the bus, or mine at a Jon Hopkins gig, can spark so much and transform the way you act. We can’t necessarily design for it or expect it, but it’s totally possible to achieve it.”

Jennifer Crook

The WXO Take-Out

We think there’s so much to be learned from the work that Crook and her cross-disciplinary team did with Dreamachine. A few particular things that stand out:

- The idea of what Laura Hess calls “holistic immersive”: the opportunity to iterate and prototype in a way that would benefit both the audience and the experience. These opportunities are still rare, so a case study like Dreamachine is a valuable model in how to do it.

- The upending of what we think we know about the beginning, middle and end of an experience. Normally we guide people through the narrative of the Hero’s Journey, but here there’s almost no beginning and no end, just constant iteration and reflection.

- The value of “small awe”. We often speak about the tremendous amazement of nature and how it makes us feel small – but the kind of awe we experience at Dreamachine makes us go inward and see how vast this internal landscape can be.

- That metrics have their place, but what we can’t measure is equally important.

So next time you’re designing an experience, ask yourself:

- In a large-scale collective experience, how can you design for the individual?

- How do you embed audience research into your R&D process to deepen the impact of a temporary experience?

- How can different disciplines work together to create something far more than the sum of their parts?

To see the full line-up for the WXO Campfires Season 6, click here.

To apply to join the WXO and attend future Campfires, click here.