In 2021, creative director David Bassuk received a very mysterious email: “Would you be interested in helping create an alternate reality game for the United Nations Assistance Mission in Iraq (UNAMI)?”

Although the invitation itself seemed like an invitation to an Alternate Reality Game, he connected anyway.

Since then, Bassuk has been working as a senior advisor to the UNAMI team in Iraq. He teaches pervasive game design and transmedia storytelling to a group of university students and postgraduates from six cities in Iraq: Erbil, Sulaymaniyah (including Halabja), Dohuk, Najaf, Basra, and Dhi Qar.

Bassuk has been producing and teaching transmedia for pretty much as long as it has existed, starting his first course in 2008 as part of a career that spans immersive theatre, LARP, immersive technology and AI.

He’s a professor at Purchase College, State University of New York, where he teaches courses including Transmedia & Performance, Immersive Storyworlds, and Immersive Narrative & Interactive Media. He’s also Creative Director of White Horse Immersive in China, known for two major projects: the immersive activation Monsters in the Forbidden City, and The Wishing God.

In May 2022, he led a five-day workshop course in the city of Erbil in Kurdistan, northern Iraq. The task was to generate an immersive creative narrative and game design specific to each city, and the goal was to design projects for young people across the country to support, educate, and motivate teachers and students on climate change issues.

When the games launched in the six cities, six coordinators led their teams in festivals, which gave rise to a combined national hackathon event in Baghdad. The games and festivals generated over 100 proposals that were narrowed down to a final 20 teams participating in the week-long hackathon, where they presented their proposals to supporting government officers, NGOs, and the environmental science community.

The 2022 program’s success has led to increased support, enabling UNAMI to expand to nine cities this year and incorporate an additional larger youth action group.

Bassuk tells us what he learned from the project about working in different cultures to your own, leading cross-cultural teams, and how we might use this example of transmedia storytelling to create experiences with real-world impact of our own.

Storytelling Versus Story-Living

The UN places Iraq among the top five countries impacted by climate change most worldwide, with increasing loss of arable land due to sanitisation, less rainfall, prolonged heat waves, and an onslaught of dust storms.

This affects young people in particular, who feel a deep sense of pessimism about the future of their country.

For this project, Bassuk taught a team of young Kurds and Arabs who had been brought together by the UN to become a collaborative working community. They spanned very separate cultures and design principles, but together sought to answer the questions:

- How might using games lead to an increased participation by young people in Iraq?

- How might young Kurds and Arabs learn to create a new partnership through play?”

“It’s storytelling versus story-living. The story of climate change is many stories at once.”

David Bassuk

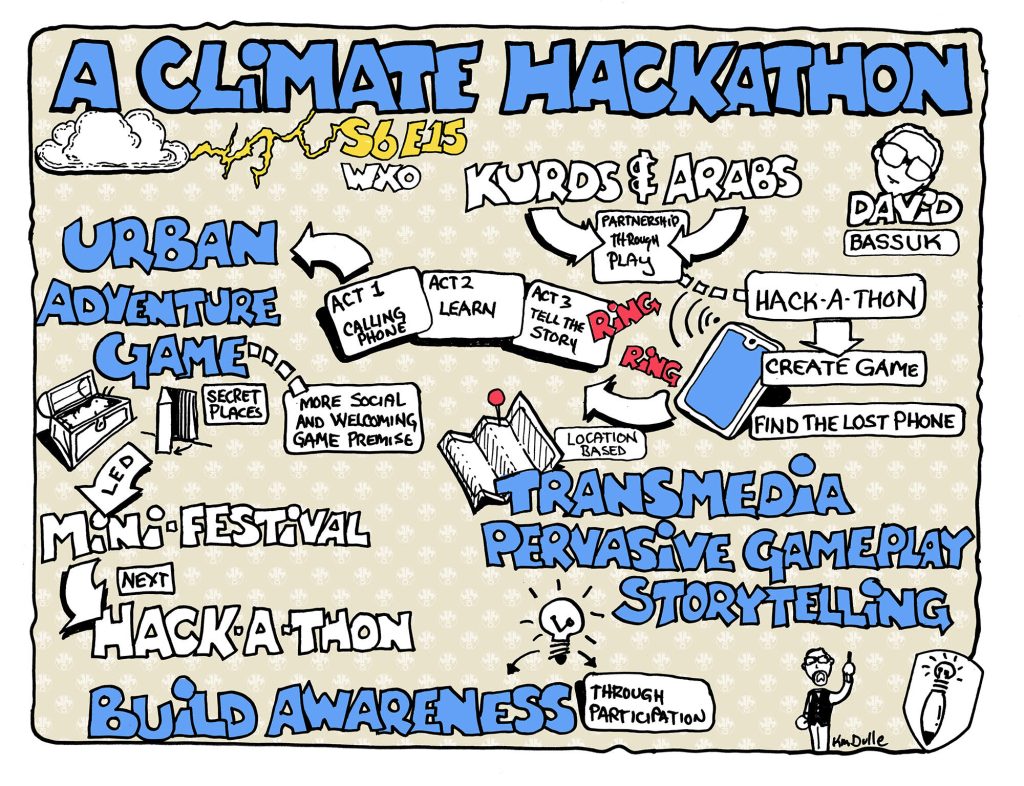

The initial phase of the project in 2021 saw Bassuk meet with two Kurdish writers to plan the narrative for a prototype climate-themed augmented reality game (ARG). They had a premise for a game and a hackathon: a collider to get ideas and proposals.

The premise for the ARG was “A Time-Travelling iPhone”. A visitor to Erbil loses their phone and it’s answered in 1974, starting a dialogue about changes to nature and the climate. The game involved political and social history, but also pulled in a parallel environmental history.

The game was run in three cities and was moderately successful, but faced problems of participation, especially for young women. More successful in Erbil. Despite this, UN advisors thought it was successful enough to merit more time and funding, and the second phase of the project began. A hackathon was also run in December, where contestants submitted proposals on climate and water scarcity to build awareness and motivation for the young.

The “Game, Festival, Hackathon” Framework

Building on these earlier experiments, in 2022 Bassuk ran a series of online and in-person meetings with UNAMI leaders, the six city coordinators, and the eight 2021 hackathon finalists. This included a seminar in Erbil consisting of a workshop on transmedia, pervasive gameplay, and location-based storytelling. The goals were to use a youth approach to pursue public awareness, get representatives to talk about water scarcity and climate change, and get concerns widely known with educators of all levels.

Together they innovated the concept to launch a more social and welcoming game premise: the Urban Adventure Game. It consisted of treasure hunts and secret designed spaces, run by six coordinators in the six cities. This was much more social, creating connections between schoolmates and different clubs. You’re more able to transcend the individual in a communal experience, and feel more able to effect change.

“Games are a fun tool and useful for social engagement. Parts of the UN are interested in doing this.”

David Bassuk

Or as Julia Eisenlöffel puts it, games create a “safe space” of having rules to follow, but also the freedom to have fun.

“It creates a beautiful container. The more you interact with other people, the more you value and appreciate them and create a feeling of belonging.”

Julia Eisenlöffel

In particular, Bassuk remembers a pivotal day when he started listening to how the young people involved felt like they couldn’t do what was being asked of them with regards to creating a positive message around climate change.

“They didn’t want to think about the climate – it wasn’t something to gather young people around, and sounded heavy and educational. Working for young people is more motivating for them – it’s about building a future and society based on love and friendship, not about these years but those years coming. This reframing helped.”

David Bassuk

The creation of the game then led them to think about what might make people participate. The idea for a mini-festival arose from the discussion: it was social, physical, and had food and drink. The gratitude sparked by these festivals also meant that people were willing to listen more to the core message: enthusiasm led to awareness.

This chain makes us think of the 4-step process for generating electricity at Anfield football grounds, and the ritual chain to transform spectators into superfans. By creating a series of thresholds to cross, people were drawn in deeper.

This game design formula could be differently designed to be unique to each city. Even though the festivals were very different, they all happened on the same day to maximise visibility and awareness and generate proposals for the hackathon, the ultimate end of the chain. The goal was awareness through participation, generating enthusiasm and motivation.

“The more you allow people to innovate, the more you get buy-in and better ideas.”

David Bassuk

This game-festival-hackathon model was very successful, and in 2023 the plan is to repeat the online classes, two-week teaching seminar, games and festivals, and finally the hackathon model.

The Importance Of Leaning Into Your Differences

Working with a collaborative team of Kurdish, Arabic and English speakers, in a community far away from home, presented several challenges – and opportunities to learn – for Bassuk.

Firstly, and perhaps most obviously, were challenges of translation. This involved not only being patient while translating between languages, but also paying attention to everything from body language to tone of voice.

“It became an important part of my work and between the Arabs and Kurds to be generous with each other.”

David Bassuk

To help the groups understand each other as well as the power of transmedia storytelling, as an early exercise Bassuk asked them to think about a room of memories of their childhood, filled with the music and things they liked to do or play that potentially aren’t available to them now. He then asked them to make a museum of memories of their region and present them to each other.

The final part of the task was to design an opening-day festival for the museum with a three-day lead-up consisting of media, parties, games, and day and night events.

“That’s the beginning of understanding transmedia. It was something they could unroll over the course of two months, and offered multiple entry points into the storytelling.”

David Bassuk

This also gave the separate regions an opportunity to show pride and belonging in their culture, and then come together to work on climate change and see their commonalities. A third step could be to look at their differences again, but appreciate or learn from them instead. Solving problems helps to create community.

“This is an example of the simple power of getting people into a room together. You don’t need to talk about cultural differences, pain or trauma – you just need to create a safe container where they can be trusting and let that play out. Once you take them out of that container, how do you hold that and keep that coming?”

Ricky Thomas

Co-creation at the beginning of a project is a key tool for finding out what Pigalle Tavakkoli calls “those things you don’t know you don’t know”. Having a clear onboarding process inviting everyone to share their mission, vision and goals is also important.

“I’ve done a number of consulting projects, and I always start with a student mindset: enthusiastic and there to learn about their culture.”

Scott Levkoff

Whether we’re working in a completely different culture or our own, this attitude is still relevant in each of the experiences we create. You never know quite where someone is coming from, and creating a shared language is crucial to achieve your aims – see How To Bring Different Worlds Together for more tips on how to design and build experiences in interdisciplinary teams.

The WXO Take-Out

The beauty of transmedia storytelling is that it’s not about telling people what to do: it’s about trying to figure out what people want and giving them multiple ways in.

“We don’t want to put things in order in the transmedia sphere – it’s a storysphere, and has multiple entry points. It’s not about the story I want to tell you, but about the story that comes out of the process.”

Klaus Paulsen

Bassuk’s project, where different cultures and perspectives came together to try and tell the complicated, multidimensional story of climate change, was a fantasic opportunity to use transmedia and immersive storytelling tools to have a real impact.

“Erbil is ready to become a modern city. Kurdistan is poised to either tip backwards or forwards. It was an extraordinary, immersive experience to make a project like this, and an education in the best way to lean into differences.”

David Bassuk

So next time you’re creating an experience, ask yourself:

- How might you use the “games, festival, hackathon” model in your own experience?

- What multiple entry points could you use as a way into your experience?

- How will you onboard people into your experience without knowing their whole story?

To see the full line-up for the WXO Campfires Season 6, click here.

To apply to join the WXO and attend future Campfires, click here.