Aga Szóstek, PhD, is a Co-Founder of the WXO, a strategic experience designer, and author of The Umami Strategy: Stand Out By Mixing Business With Experience Design. She has previously written about Why Brands Should Ask Their Customers To Break Up With Them and led a workshop for Campfire 22: New Metrics For A New Economy.

Here she discusses why the stages of economic progression as defined by Pine & Gilmore shouldn’t stop at human transformation, but should transcend it to “regenerative socialisation”, a way of living that puts the Earth first and humanity as part of its ecosystem, not superior to it.

- We are already moving from the era of consumerism to that of experientialism.

- The experiences of the future will not only aim to be fun or pleasurable, but truly transformational.

- However, why should the stages of economic progression end here? What is the point of human transformation on its own?

- Szóstek argues that it’s time to enter the era of “regenerative socialisation”: a way in which humans relearn how to be a meaningful part of Earth’s ecosystem, rather than its most destructive force.

Oceans are a crucial part of our ecosystem that produce oxygen. Yet we treat them as a free food resource that can be exploited without as much as a “how do you do”. Animals create a complex system that enables our planet to function in a fairly homeostatic state. Yet we don’t even blink when another animal species disappears.

There’s almost no point in talking about the Amazonian forest, or any other forest for that matter. As humans, we seem to see all of what nature offers not as a gift to be revered, but as something we have a right to use as we please. It would be hard to find a better summary than the old saying “sawing a branch on which we sit”.

The Pitfalls Of Consumerism And Rise Of Experientialism

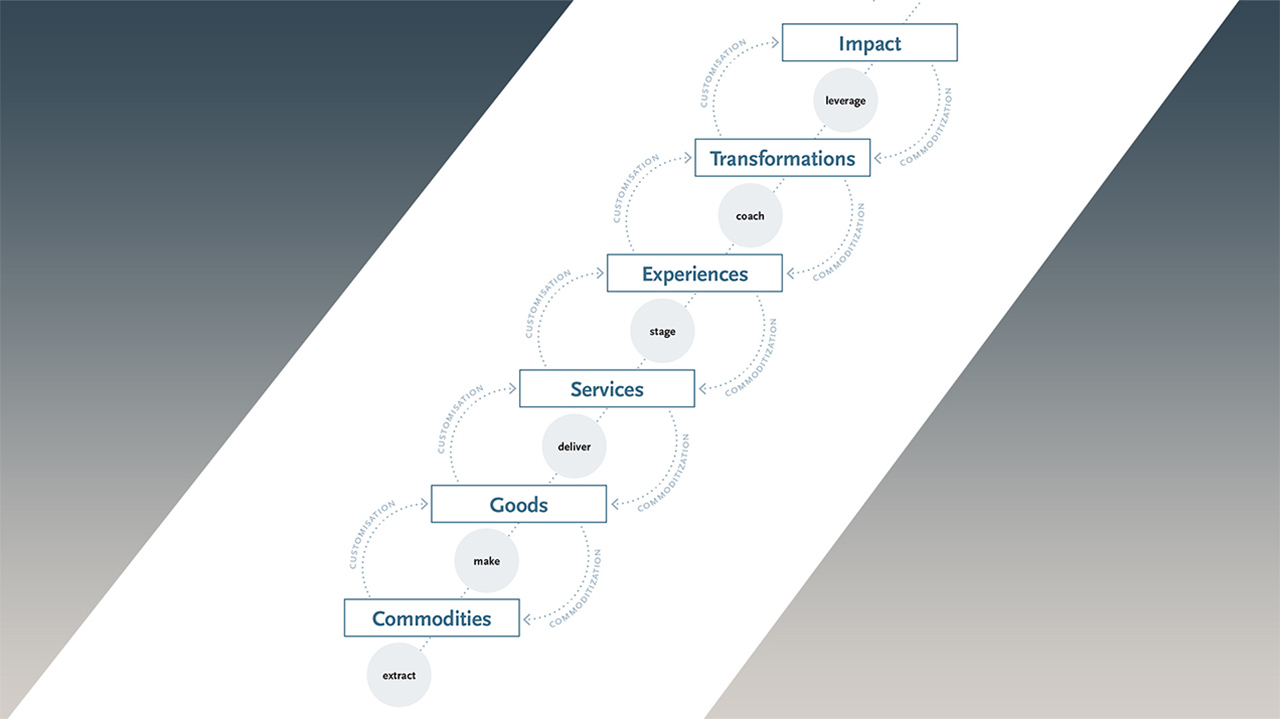

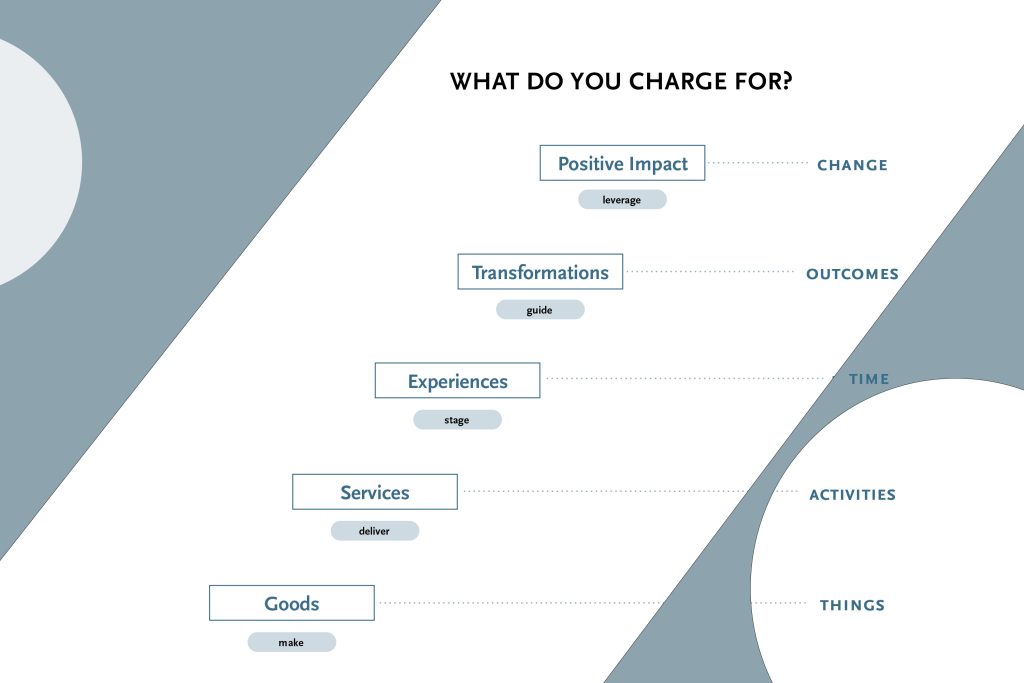

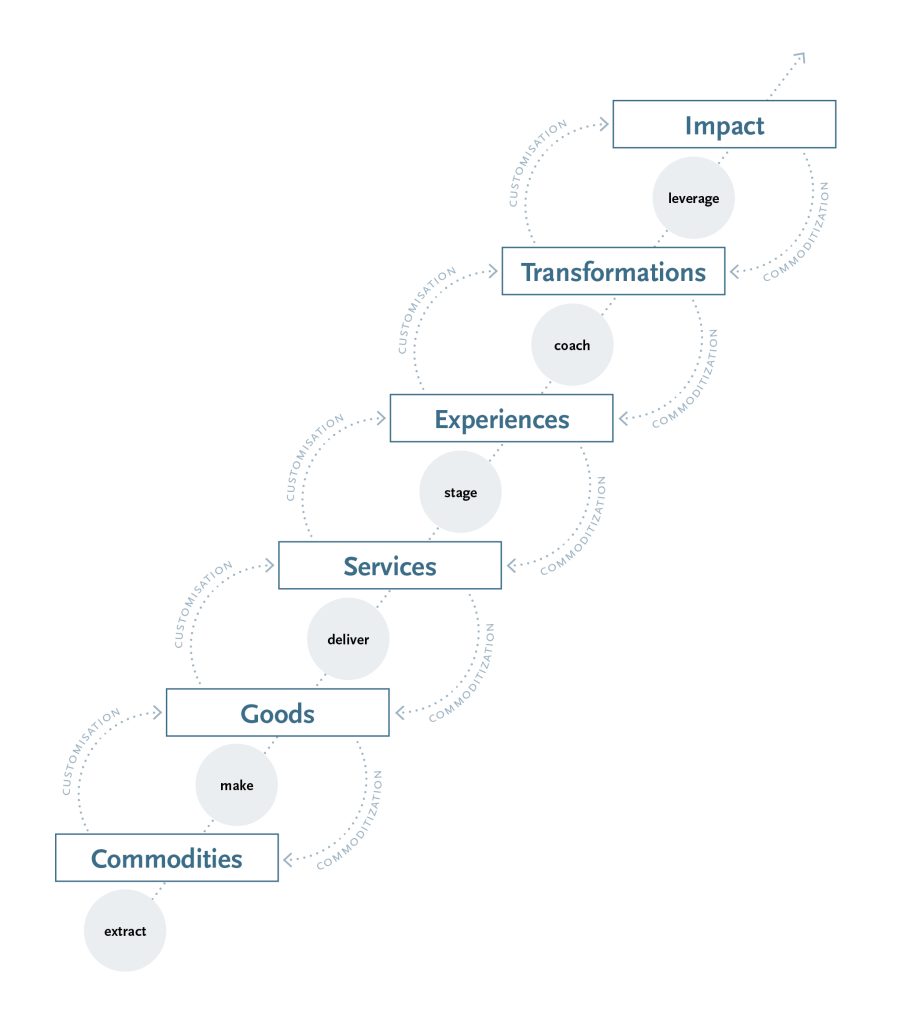

Back in 1993, Joe Pine and Jim Gilmore had an incredible insight into what the progression of our economies was likely to look like. They observed that as the world of humans evolved, we moved from extracting commodities to selling goods, offering services and, fairly recently, entering the space of staging experiences as a way to create a competitive advantage in the market. These steps are rooted in the consumerist economy that has bloomed since the end of the Second World War.

However, more and more people and organizations realise that consumerism is a slippery slope for humanity in a not-so-long-any-more timeframe. With the dawning of the era of experientalism (as James Wallman, WXO CEO and the author of Stuffocation and Time, And How To Spend It, calls it), we are hopefully on the brink of the first turn of the tide.

Well-designed experiences are not only more appreciated and longer remembered, but also, hopefully, less taxing on the environment. They already aim to be fun but, as Pine and Gilmore’s model predicts, more and more of them will aim to become meaningful and even transformational.

Why Stop At Transformation?

Mat Duerden, the co-author of Designing Experiences, talks about small and capital “T” transformations. Small transformations are the little changes we face that alter the way we see the world. We may not see them happening to us at a given moment, but over time they make us alter our perspectives, opinions and attitudes.

There are also capital “T” transformational events – situations that dramatically alter the ways in which we see the world or ourselves. They can happen to us or can impact us indirectly, but their sheer power of influence is noticeable and significant. They make us into new, hopefully better versions of ourselves. We transform to live more meaningful, more fulfilled lives. We transform to be better partners, parents, leaders, citizens. We transform to be the people we dream to be. Products, services and experiences can help and guide us on that path. But to what end?

“We transform to be better partners, parents, leaders, citizens. We transform to be the people we dream to be. Products, services and experiences can help and guide us on that path. But to what end?”

Aga Szóstek

I’ve always felt that transformation cannot be the end of the economic progression model: that there is more on our human “event horizon” (as articulated in Design to Change by Roel Frissen, Ruud Janssen and Dennis Luijer). As I kept working in the field of experience and transformational design, I kept facing a question: what for? What is the underlying purpose of the experiences we stage? Should there be one? What is the transformation we hope to guide? Should it be guided towards a specific direction?

I am certain that many experiences are, and should be, designed for pleasure and fun. I am also convinced that a multitude of transformative designs are right to aim to aid people in leading a more fulfilled life. Many of these designs are focused on an individual living through and changing things about and around themselves.

Leveraging Impact From Transformation

But I believe there is more. I believe that there is a seventh stage of the economic progression model, and it is contributing to leveraging the impact that stems from our transformational process.

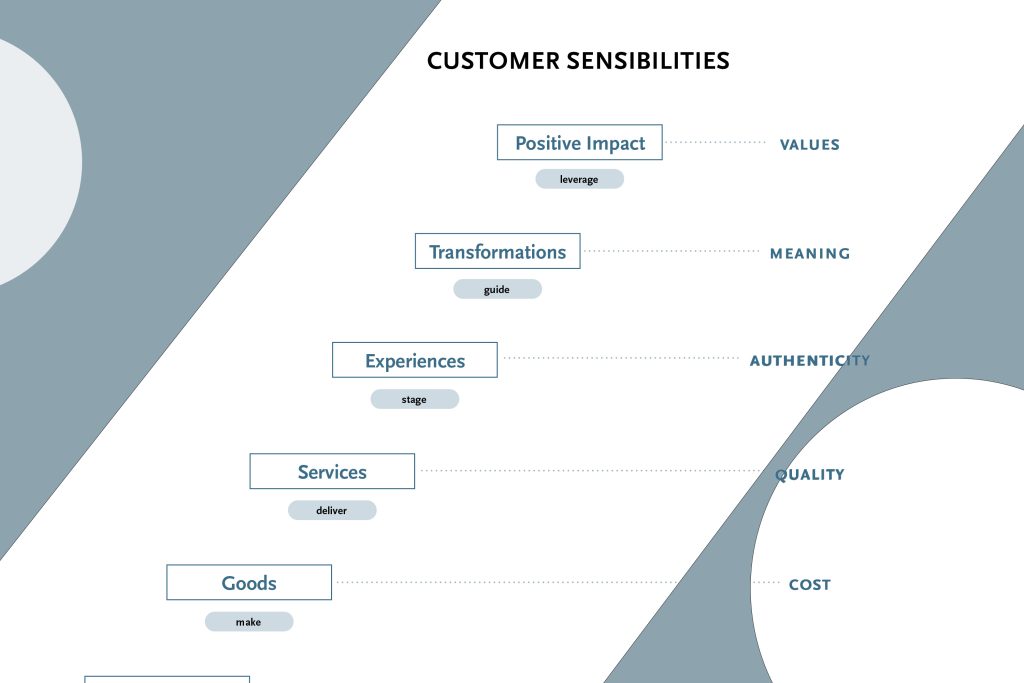

Leveraging impact means that as transformed people, we decide to consistently choose products, services, experiences and transformations that align with our direction of change, be it our values, ideas or the image of the world as we would like to have it.

So, while Pine and Gilmore talk about time well saved, time well spent and time well invested for services, experiences and transformations respectfully, I would add time well leveraged as a representation of leveraging impact.

In the Aristotelian framework it can be seen as turning from the hedonistic approach to life represented by commodities, goods, services, experiences and to an extent transformations into a eudaemonic approach to life, where we see our actions as actions not only for our own comfort, joy or development, but also as means to positively impact the world we live in. As a consequence, we decide to choose offerings that help us have such eudaimonic impact. In terms of customer sensibilities, it means that our consumer choices are based on our values rather than just personal meaning.

Much like experiences and transformations, positive impact can be seen as a complex economic offering. Commodities, goods and services are building blocks that can stand on their own – they don’t need an extra “flavor” (to use my umami metaphor) to exist in the world.

When it comes to experiences and transformations, these are higher-order elements – an experience and transformation can’t really exist without goods and services. There can be a set of goods and services that “replicate” what transformation or experience offers – but without the crucial ingredient, which is a conscious focus on experience or transformation, they are just a bunch of goods and services stuck together.

As Lance A. Bettencourt, B. Joseph Pine II, James H. Gilmore, and David W. Norton mention in the recent HBR article The “New You” Business, you can have all the elements of a transformational fitness club put together – the space, the subscription, the trainers, the dietician, etc – but without conscious design, it’s not going to be a transformational experience offering (although, surely, many people can undergo a transformation there based on their introspective need to change their lifestyle or lose weight).

The impact I am talking about is a set of goods, services, experiences and transformations that have a higher purpose, and that higher purpose becomes a reason to buy. It is an economic shift. It is something that people are willing to pay for and “vote for with their money”, which in terms of economic progression is a willingness to pay more for seeing the actual impact on the world as they like it to be. It may seem intangible, but so are transformations. The main difference is the shift from individual to collective benefits, as aptly put in the most recent “Meaningful Brands Report” (2021) by Havas.

Introducing Regenerative Socialisation

Such process could be called a regenerative socialisation of companies and brands. As consumers, we would only choose the offerings that contribute to the change we want to see in the world (and I don’t mean some CSR activities run on the side of the main business, but instead a truly impactful way of corporate being, very much like Patagonia does). It may be a surprising phrase, so let me explain what I mean by it.

According to Ian Robertson (Sociology, 1977), there are four types of socialisation known in human societies: primary socialisation, anticipatory socialisation, resocialisation and developmental socialisation.

Primary socialisation is a process of teaching children the rules and norms of the society they find themselves living in. It includes the teaching of language and cogitative skills, the internalisation of cultural norms and values, establishment of emotional ties, and the appreciation of other roles and perspectives.

Sometimes, however, we may find ourselves planning to join groups whose norms we may not know: for example, we may plan to move to another country, or join a new organisation or social circle. In anticipation of that, we may learn the norms and rules of that new group so we are better able to fit in.

Contrary, we may also find ourselves having to unlearn certain norms and rules in order, for example, to rejoin our former social group. If you’ve ever moved back to your country after living abroad for some time, you might have experienced this.

Finally, developmental socialisation. As Robertson states, “It builds on already acquired skills and knowledge as the adult progresses through new situations such as marriage or a new job. These require new expectations, obligations, and roles. New learning is added to and blended with old in relatively smooth and continuous process of development”.

“What if human development is not the ultimate answer? What if the economic progression should not end on our species, but transcend it?”

Aga Szóstek

These types of socializations all refer to human’s ability to change and progress. But what if it’s not enough? What if human development is not the ultimate answer? What if the economic progression should not end on our species, but transcend it? What if we need a new type of socialisation, regenerative socialiation — a way in which humans relearn how to be a meaningful part of Earth’s ecosystem, rather than its most destructive force? Could this become the seventh stage of economic progression, going beyond leveraging impact?

A Posthumanist Future: Sci-Fi Or Reality?

In the philosophical movement called posthumanism, a lot is being told about dethroning people as the superior species and finally admitting that without the objects we use, we are not able to do much.

What is missing from this movement, though, is the realisation that we are not only incapacitated without objects (analogue and digital) that help us to perform most actions in the world, but also unable to live without the natural ecosystem that surrounds us. We are only beginning to learn about the role of the oceans and the life in them in the process of Earth’s oxygenation.

Yet, we see them as a free resource we can exploit at little cost. The same applies to the soil, the forests, and the natural world that surrounds us. And yet we somehow assume that we are, as humans, better than it, not quite pondering the consequences that are in it for us if we take a step too far and grab too much.

In the last books of the great series Foundation (Foundation’s Edge and Foundation and Earth), Isaac Asimov raises the question that we should start asking ourselves right now: is humanistic individualism better than ecosystemic interdependence? The main character in these last two books, the Terminus councilman Golan Trevize, is known for being able to make correct decisions under extreme uncertainty. Unwillingly and rather unconsciously, he is sent to the planet of Gaia to decide which of the two systems should prevail in the Galaxy.

He makes a decision he is deeply unhappy about and in deep personal disagreement with. He chooses the Gaia way, which basically means that all decisions are made for the good of the planet: not just one species, the humans. So he sets out to travel the galaxy to find Earth, and confirm or reject his gut feeling. He travels through the planets colonialized by humans in the early era of galactic expansion and sees the long-term consequences of what individualism might lead to. I wonder what would have been the next book in this series if Asimov had a chance to write it.

“Are we willing to see humans as a part of the ecosystem rather than a user (and often abuser) of it? Being an optimist, I hope the former happens rather than the latter – and if so, the 6th step of economic progression will become crucial to inflict the change that will be necessary.”

Aga Szóstek

Obviously I realise this is fiction, and as fiction it is a creation of human imagination. However, many science fiction writers of their times had sort of prophetic abilities, thinking of Verne to start with. And I believe we might, sooner rather than later, face a challenge much like Trevise did. Are we willing to see humans as a part of the ecosystem rather than a user (and often abuser) of it?

Being an optimist, I hope the former happens rather than the latter – and if so, the 6th step of economic progression will become crucial to inflict the change that will be necessary. It will be a way to use our personal transformation to redesign our world in ways that are collaborative and respectful to the place that supports us, and which we hope will support humans in the decades and centuries to come.

To get more insights from experts in the Experience Economy like Szóstek – and to be the first to know about our membership programme, events and more – apply to join The WXO here.