Bert Smit is a Principal Lecturer at Breda University of Applied Sciences. He specializes in designing and design evaluation of customer experiences, combining insights from social science with methodology from design science.

Here he explains how whether you’re designing a zoo, a hospital, an office or any other kind of experience, the same methodologies apply.

It was when the silverback gorilla looked me in the eyes that I realised that we weren’t just designing a new attraction for our guests and a workplace for some of my colleagues, but also a home for his rather large family of 20 gorillas.

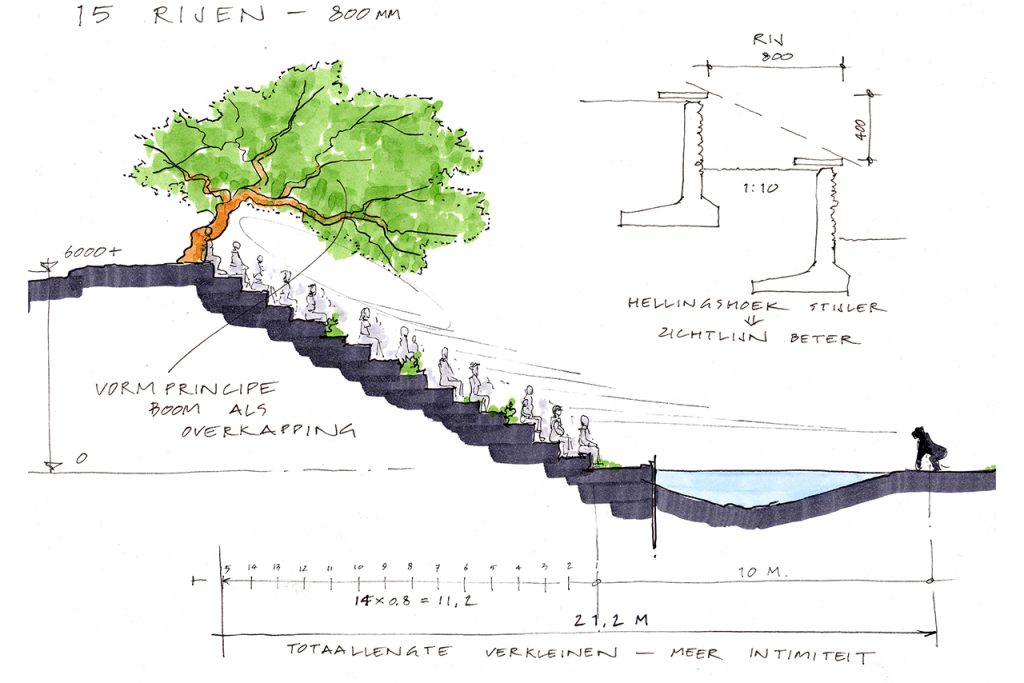

I was part of a multidisciplinary team developing a new master plan for Apenheul Primate Park in The Netherlands in 2005. The existing outdoor gorilla exhibit of roughly one hectare (2.5 acres) was being upgraded with a new indoor facility, which would be the home of the gorilla family and several other species, as well as a key element in our storytelling around conservation education. The estimated investment of 5 million euros would hopefully turn it into one of the key attractions in the zoo.

It wasn’t until much later that I understood the experience we were hoping to design to get our conservation message across would never be the same for all our guests, but would depend on the personal, social and temporal aspects of visiting the zoo and each specific exhibit. And even longer to understand that what we’d learned from the project applied to not only zoos, but anywhere you’re designing for an experience.

Designing For Different Purposes

“Sometimes relatively small investments had a big impact, whereas some major investments never resonated in the way we expected. “

Bert Smit, Principal Lecturer, Breda University of Applied Sciences

It took months of observations and small interviews to understand what functions the zoo was providing to our guests that made them decide to spend their scarce time and money with us.

We came to understand that for a lot of guests, our amazing animals were no more than an excuse for spending quality time with their family, whereas for others the zoo served as nature education to their children, or an ideal environment to test technical skills developed in a photography course (but preferably without kids running around).

We already understood intuitively that the quality of life of our animals positively contributes to the experience of our guests and the job satisfaction of our staff. However, we also knew that investment in animal exhibits needed to be balanced with safety requirements and limitations of budget and space.

In the end, it was the unpredictability of the return on experience (ROX) of our investment that made me go back to academia. Key indicators for this ROX were:

- Average length of stay (the longer the stay, the higher the revenue in catering and merchandising)

- Visitor return rate

- Time in between zoo visits

- NPS

- Changed consumer behaviour

Sometimes relatively small investments had a big impact, whereas some major investments never resonated in the way we expected.

The Relative Stress Of Rollercoasters And Hugh Grant

“How do you interpret stress or anxiety on a rollercoaster vs during a hospital visit? Is it a bad thing that my wife sobs when Bridget Jones gets dumped by Hugh Grant (again) while I am bored to bits?”

Bert Smit, Principal Lecturer, Breda University of Applied Sciences

Now I’m based at Breda University of Applied Sciences, where we (among others) explore how we can design for experiences with different stakeholders, and how we can measure and benchmark their experience quality. You may have noticed that I’m not talking about “designing experiences” but “designing for experiences” This choice of wording is deliberate. It’s the result of a debate I have been having with other experience enthusiasts for a while now.

Some of my academic colleagues measure neurological activity, stress levels and emotional responses to test a particular experience – but how do you interpret stress or anxiety on a rollercoaster vs during a hospital visit? Is it a bad thing that my wife sobs when Bridget Jones gets dumped by Hugh Grant (again) while I am bored to bits? To interpret this kind of data you need a lot of contextual and personal information. In most cases there are simply too many internal and external variables at play to make sense of biometric data. As a result, I cannot predict exactly what the strength of the neurological responses of each individual will be to what I design.

In my view, the visitor evaluation of the experience they had and the memory the visitor creates and recalls are more important indicators of successful design. Moreover, these are things I can set design objectives for. For instance, a design objective could be “visitors should remember our restaurant as the best place for a romantic dinner”, “guests should feel inspired during their stay at our hotel” or “after visiting us, guests should understand that humans are destroying the habitat of gorillas in pursuit of rare minerals”. I can even specify these types of objectives for different groups of users that visit a particular place for different reasons, allowing further customisation of the experience by developing personas of a diversity of different users.

The Universal Contexts Of Experiences

“Any experience is formed by the physical context, social context and personal context in which it takes place.”

Bert Smit, Principal Lecturer, Breda University of Applied Sciences

Since my switch to academia I’ve been involved in designing for experiences in the most hospitable hospital of the Netherlands, head offices of several financial institutions and tourism destinations such as Rotterdam. This is where I discovered that similar principles apply to many different places.

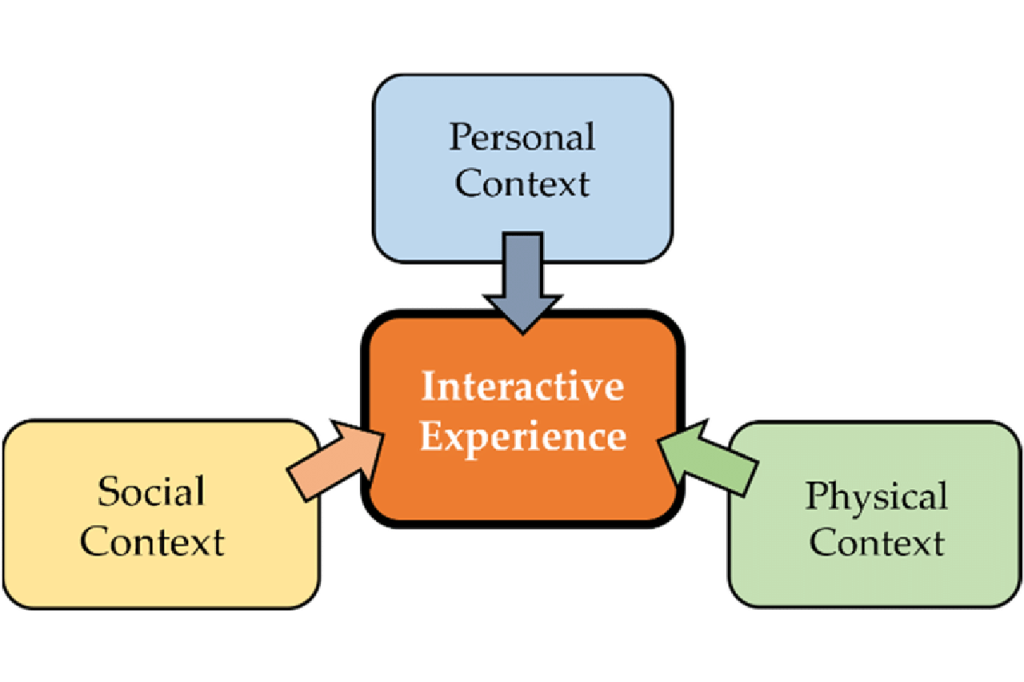

How are they similar, exactly? To date I haven’t come across a better or simpler framework that explains this than the interactive experience model by Falk & Dierking (1992). Although originally developed to explain learning in museums, the framework can be extended to almost any other place, as it simply explains that any experience is formed by the physical context, social context and personal context in which it takes place.

Physical Context

As a designer I can influence almost anything in the physical context – for instance what you see, hear or smell. In the zoo for instance, landscaping design made it possible to hide almost all fences and gates, which in combination with soundscaping created a very immersive experience. Similarly, attractive workplace design can have a major impact on corporate culture, productivity and talent retention.

Social Context

As a designer you can also to some extent determine the social context in terms of who and how many people you see and the type of audience you would like to attract or deter. The hospital we worked with, for instance, provided possibilities for having family dinners in a living room setting with a la carte meals, which made the hospital stay for patients much more bearable, leading to quicker recovery.

In office design, deliberate choices can be made with respect to which colleagues you share a space with, how and where you have lunch, etc. When I visit the zoo with just my kids I have different needs than when I bring my granny or my students. In my design I can make deliberate choices with respect to facilitating these needs.

Personal Context

What I cannot influence directly as a designer is the personal context in terms of preferences, values, taste and previous experiences. I wasn’t bored the first time I watched Bridget Jones. My wife gets nauseous on roller coasters while I have a blast. A persons’ needs and wishes are situational (mood and biological state), but also result from their identity and personality. That is why the same experience will not result in the same neurological response in different people. What we can do, however, is be explicit about who might like the experience we design – and who might not – in our marketing.

User-Centred Vs Human-Centred Design

“Don’t expect an NPS score above 15…[if you try to] please 100% of the guests by focusing on elements of the experience that are important to the average guest, but not every guest.”

Bert Smit, Principal Lecturer, Breda University of Applied Sciences

This way of thinking is essential in user-centred and human-centred design methods. User-centred design focuses on technical aspects of design of different (individual) users, for instance in developing games and cars. Human-centred design goes beyond that by also incorporating social and organisational aspects in the design, for instance the role of employees, impact on society, and interactions between people that are part of the experience.

By contrast, I see a lot of companies in the Experience Economy focusing on user-centred design, standardising their operating procedures to serve the average guest with a particular set of demographic characteristics. Most of the 4-star hotels of major brands are designed this way. That is why most guests cannot tell whether they are in a Hilton or Hyatt when asked. This is not necessarily a bad approach, but don’t expect an NPS score above 15, as this type of design tries to please 100% of the guests by focusing on elements of the experience that are important to the average guest but not every guest.

Escape The Commoditization Trap

Pine & Gilmore already pointed out 25 years ago by walking a mile in the shoes of your guests and appreciating their differences. That’s when you find out why they choose to spend their time with you and what they hope to get out of it. It’s when you realise that some people in the hospital are stressed because they wanted to be in time for visiting hour to see granny, but couldn’t find a parking spot. Or when you realise your guest didn’t come to your restaurant for food, but because she is falling in love with the other person at the table.

A Touch Of Animal Magic

“The experience industry needs to be aware of and embrace the differences of its guests and staff in designing for their experiences within the boundaries and purpose of their company.”

Bert Smit, Principal Lecturer, Breda University of Applied Sciences

So to get back to the workplace needs of gorillas and pandas. If they are to be happy and healthy as individuals and families, we need to facilitate their natural behaviour as much as possible through customised design within the financial, legal and physical boundaries of the zoo.

Gorillas live in big groups, where the silverback is in charge as long as the women allow him to be. They move around looking for food most of the day and build a nest every night in a high place. Pandas are solitary animals most of the time, except for the couple of days a year a female is fertile. They are strict vegetarians but don’t move a lot if they don’t have to.

Similarly, the experience industry needs to be aware of and embrace the differences of its guests and staff in designing for their experiences within the boundaries and purpose of their company. They are not all the same either, but they did have something in mind when they choose to go out and seek your experience.

To get more insights from experts in the Experience Economy – and to be the first to know about our membership programme, events and more – apply to join the WXO community now.