How can science inform the design of your experience’s technology and story?

We’re really excited about the growing wave of neuroscience-inspired, “functional” experiences – see Dreamachine, The Hum, and The Uncertainty Experts, for starters.

And Theater of the Mind, the neuroscience-themed immersive experience from Talking Heads frontman David Byrne, stands at the crest of this wave.

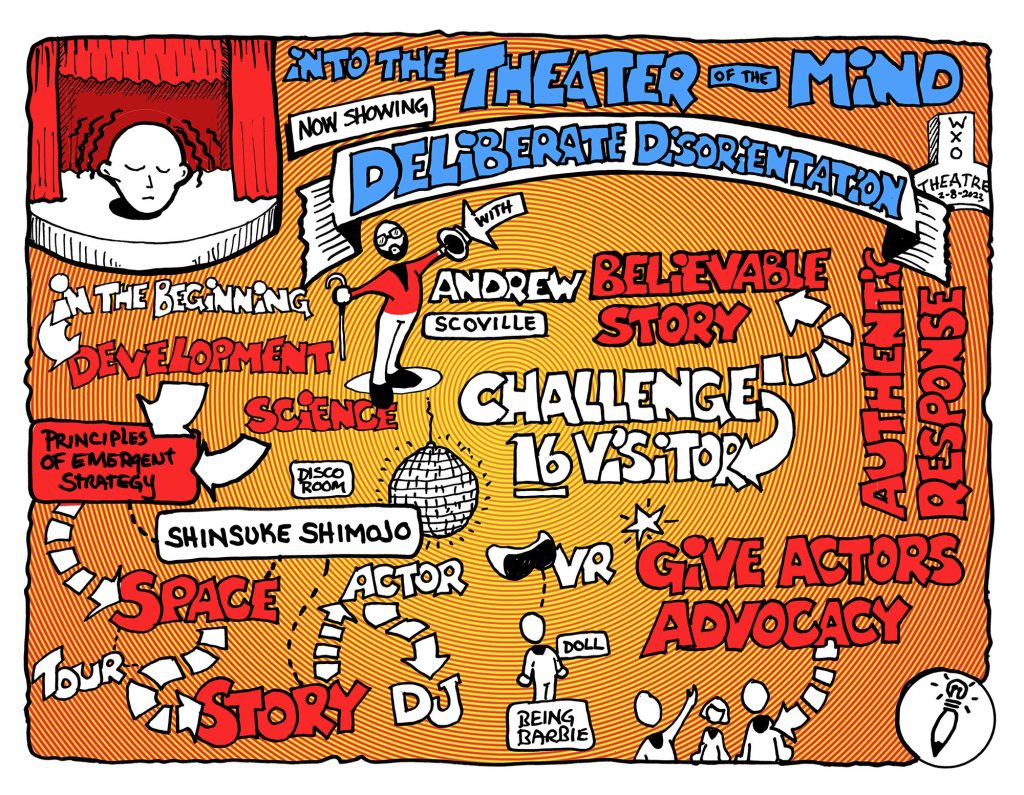

A playful intersection of art and science based on lab research, the (now closed) experience invited participants to explore a 15,000-square-foot immersive art installation, engage in a narrative, and take part in multisensory experiments that encourage them to interrogate their identity and understanding of the world, and question their beliefs and memories.

The scientific phenomena explored in the show weren’t layered onto the story: they laid the groundwork for the different environments, technology design, and story of the show. Every 15 minutes, 16 audience members departed for a 70-minute tour of different environments including a funeral chapel, disco, backyard, attic and oversized kitchen. Each location was rooted in one or more science phenomena or neuroscience studies and was interactive and experiential.

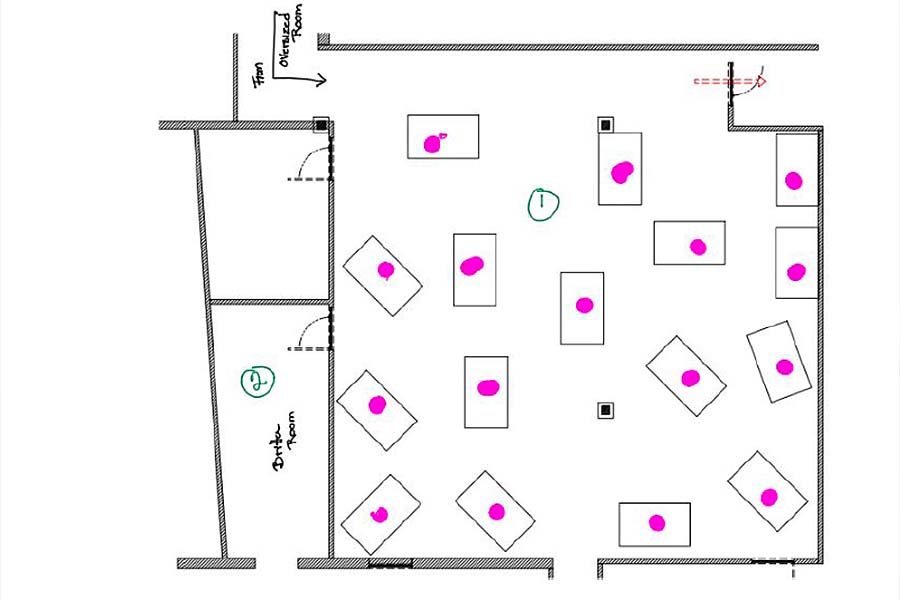

Take a look at the flow here:

Across the lifespan of the experience, over 42,000 audience members went through the show, which had more than 2,700 performances.

We invited Theater of the Mind’s Director, Andrew Scoville, to reveal how these different threads came together – and how they were organised to rehearse actors into the show. Read on to discover his generous insights into the experience development principles he lives by, the reality of organising and launching a complex show like this, and how to make the science resonate on an emotional level.

8 Principles For Developing Immersive Experiences

When articulating how he intends to be in relationship to his work and collaborators, Scoville likes to refer to the principles of emergent strategy set out by Adrienne Maree Brown, namely:

- Small is good, small is all. The large is a reflection of the small.

- Change is constant. Be like water.

- There is always enough time for the right work.

- There is a conversation in the room that only these people at this moment can have. Find it.

- Never a failure, always a lesson.

- Trust the people. If you trust them, they become trustworthy.

- Less prep, more presence.

- What you pay attention to grows.

These principles are particularly useful in immersive work, as they speak to the ideas of process, layering, and speaking about what you need that are central to these kinds of experiences.

They’re also valuable in challenging moments of collaboration, when people are trying to achieve something monumental and all-encompassing and they might not meet their own expectations.

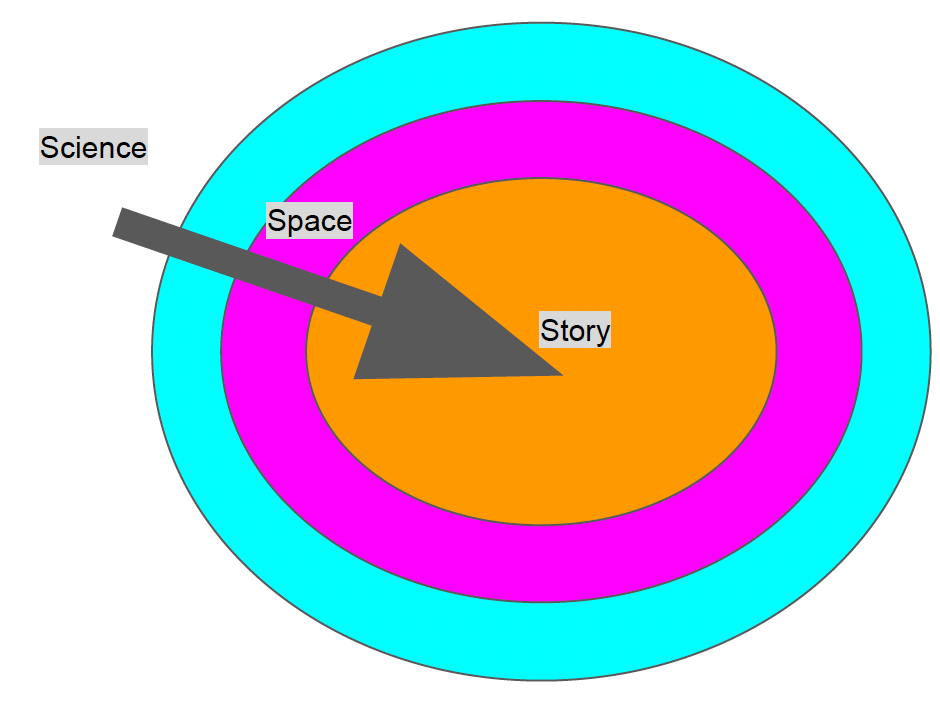

Start With The Science: Build From The Outside In

Theater of the Mind was an unusual case in that the team started with the science they wanted to experiment with, used the space to figure out the experience, and then came to the story last. This might not always be the most appropriate flow for an experience, but as scientific phenomena were the backbone of this experience, this structure worked well.

“Things got mix-y and swirly as we went on, like a soup.”

Andrew Scoville

The objective of Theater of the Mind was to create the conditions for an emotional response to real science phenomena to move the project from clinical to personal. They therefore didn’t want the audience to feel like they were participating in some kind of experiment, and believed that the science would resonate more if there was a deep emotional connection.

The parallel threads or journeys involved in this were:

- Story: looking back, I’m not who I thought I was.

- Science: dismantling preconceived sense of self

- Space: confronting an ever-changing reality and returning to a childlike state

How The Space Dictates The Story: The Disco

To shed some (very shiny) light on how this experience structure unfolded in reality, Scoville broke down one of the “rooms” within Theater of the Mind: the Disco.

The objective of this room was to play with the scientific phenomenon of motion-induced blindness, or the idea that our eye favours things in motion. The inspiration was a scientific paper called “Self and world: large-scale installations at science museums” by Shinsuke Shimojo, which offered suggestions on how to generate higher emotional impact. This was key to the project, as the brief was to focus on insights that would be experientially impactful.

The science produced a set of circumstances or non-negotiables – the most Scoville has ever dealt with as a director. The space had to contain:

- A mirror ball, like that found in a disco

- Relationship between two parties and rough distances

- Rotation of disco ball

- Light positioning

- 15-20 seconds for the effect to take place

- The impact may be enhanced by scaling up, and using a human body as a target would have a more robust response

The room could be no other size, shape or colour, down to the glossiness of the paint. Any alterations would impact the scientific integrity that was at the forefront. This left the least amount of room for interpretation.

The result was an octagonal room with “the greatest prop ever created in the history of American theatre”, the disco donut, at its core. When the disco ball rotates around a pole and people stand around it in columns (the observers) or in corners) the subjects, and when the observers stare straight ahead with the subjects in the periphery, the subjects disappear.

The number of 16 participants was specific to this effect. The role of the actor was also determined by the space – some triggers were automated (such as the sound starting up when the door opened), but others were triggered by the actor (such as showing people to their positions or starting a song).

Using Technology To Enhance The Science: The Attic

In another of the experience’s rooms, the Attic, the team wanted to test the theory put forward in the paper “Being Barbie: The Size of One’s Own Body Determines the Perceived Size of the World”. The paper explains the scientific theory of embodiment, or the feeling that you are in a body which is not your own.

The insights from the paper helped to determine the following elements of the experience:

- VR as a delivery mechanism. The space had originally been a plain white room, but was changed into an attic to help move it from a clinical to an emotional space.

- Ownership of a doll body. Audience became more attached when they had a relationship with the actor/doll, so the audience embodied a younger version of the actor (or Guide) taking them through the experience.

The final setup consisted of 16 armchairs spread throughout the space, loaded with computers to run a VR system. The chairs also had a small fan built in to replicate a sense of air brushing past them and some faint scent.

“We worked with a scent specialist specifically for the smell of grass, in our attempt to poke at the feeling of ownership. It worked for me the first time, but the other times you’re unpacking it. We primed people to tune in to that part of their experience to get them to start thinking about it, so the grass could be more effective.

While it didn’t necessarily smell like ‘real’ grass, the whole show has a later of artifice that’s a bit uncanny. At this point, you’re hopefully enough removed from reality that your disbelief has been suspended to the point where it’s delightful rather than cynical.”

Andrew Scoville

When people put on the VR headset, they would stare at a doll’s body that looks like the actor, and because of the changed sense of scale and the non-visual stimuli such as scent, they would feel ownership of the body.

Working With Actors To Bridge The Gap Between Science & Story

The key to bringing the idea that you can emotionally connect to the science home in a robust way came when actors were brought in to collaborate and bridge the gap between science, space and story.

There were 14 unique actors at Theater of the Mind, all playing the same role of the Guide. They worked entirely on set – both a blessing and a challenge! – and the show was fully baked and tech-ed up at the point that they were brought in. There was also the challenge of synthesising years of development into a digestible form that the actors could work with.

The 5 Phases Of Onboarding Actors

To get the actors up to speed within the launch timescales, Scoville developed a pyramid of phases that outlines what the priority was at which step of the process.

“When you have something fully built, it’s hard to not be able to deliver it the next day. You can’t just go from 0-100.”

Andrew Scoville

The 5 phases looked like this:

Phase 1: Learning. Going through the script as a group, working through triggers, and highlighting acting beats and tech.

Phase 2: Round Robin. Navigating through space and story beats, thinking about transitions and stamina, articulating their needs.

Phase 3: Stumble. Running through without an audience, but with tech.

Phase 4: Test Audience. Crowd control and the complexity of moving 16 people from one room to another and getting them in specific positions and to time.

Phase 5: Show time. Interacting with an audience and authentically responding.

Theater of the Mind has around one week for the Learning component, including staging throughout the show, one week for the Round Robin and Stumble stages, one week of Test Audience, and one week to do previews.

Scoville also articulated the actors’ jobs by breaking them into 4 chunks:

- Storytelling: Building a case, sharing memories with friends, journey of the guide.

- Facilitation: Effectively executing the scientific phenomena and the joy in sharing it.

- Crowd control: Moving people through spaces.

- Authentic response: Taking in and responding to what comes at you and actually listening once you’ve mastered the basics.

The role of the actors also included partnering with technology (such as hinges, door start timers, switches and buttons, and cues) and being mindful of time – for example slowing down or speeding up a performance when it’s time to move on.

Mapping The Story Onto The Space

To help articulate to the actors how their performance should change as they journeyed from room to room, Scoville mapped the dramaturgy of the experience onto the physical layout. It didn’t follow a strict three-act structure, but rather a version of the Hero’s Journey as it felt the most accessible.

Waking up in a coffin at the beginning of the experience was the call to action, entering the next room through a bookcase became crossing the threshold, and facing the self and letting go took place in the final few rooms. The impact of this whole journey was essential in order to trigger a sense of catharsis at the end.

“I normally wouldn’t suggest to an actor what they should be thinking, but it was important for this experience to deliver consistency between the story beats and the connection to the science. The Guide became an idea that we were building and articulating together, while the actors also kept individual things for themselves that would become ‘My Guide’.”

Andrew Scoville.

There had to be space for the actors to bring themselves to the role of the Guide. Those who were most successful in the role were probably 80% themselves and 20% the character. This meant that when auditioning for actors, the primary skill set Scoville was looking for was a combination of an innate sense of humour, someone who keeps people wanting to lean in and talk to them, and an ability to move people around the space.

The WXO Take-Out

We tend to think about how we might bring science into our experiences. For Scoville, this is the wrong approach.

“Instead, ask what is required for the science to occur? And what are the possibilities within that immense, detailed set of requirements?”

Andrew Scoville

Start with the science, use the space to figure out the experience, then ultimately come to the story. The science will also resonate more if there’s a deep emotional connection.

So next time you’re designing an experience and want to use science to create impact, ask yourself:

- How do scientific studies and experimentation offer unique opportunities for interactive experiences?

- How can certain technologies that are used to run a show also impact the story?

- What are some unique ways to organize complex projects when it’s time to rehearse with actors?

To see the full line-up for the WXO Campfires Season 6, click here.

To apply to join the WXO and attend future Campfires, click here.