Do you think that:

- You’re prone to sickness? Or resilient?

- You’re genetically averse to exercise? Or naturally fit and healthy?

- Stress is debilitating? Or enhancing?

- Exercising willpower is depleting? Or strengthening?

- Ageing is a time of vulnerability and decline? Or growth and wisdom?

All these beliefs could be true to a certain extent. But whatever belief you hold will likely become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The reason for this is down to what scientists call “the expectation effect”: the brain’s power to create self-fulfilling prophecies out of our beliefs through changes to our perception, behaviour and physiology (and often all three at the same time).

And this is the message of a new book based on peer-reviewed research, The Expectation Effect: How Your Mindset Can Transform Your Life by award-winning science writer David Robson, a specialist in neuroscience, psychology and medicine.

It’s not up for debate that the expectation effect exists – but its ability to shape outcomes in our lives is probably more powerful than we realise. So it stands to reason that as experience designers, by understanding the profound impact expectation has on experience, we can then seek to craft our customers’ / guests’ / visitors’ / employees’ / audience’s expectations in a way that results in more fulfilling and successful experiences.

Discover how the expectation effect could make you drink vinegar-infused beer, see ducks where others see rabbits, or even get hitched – and how you might be able to harness its power in your own experiences.

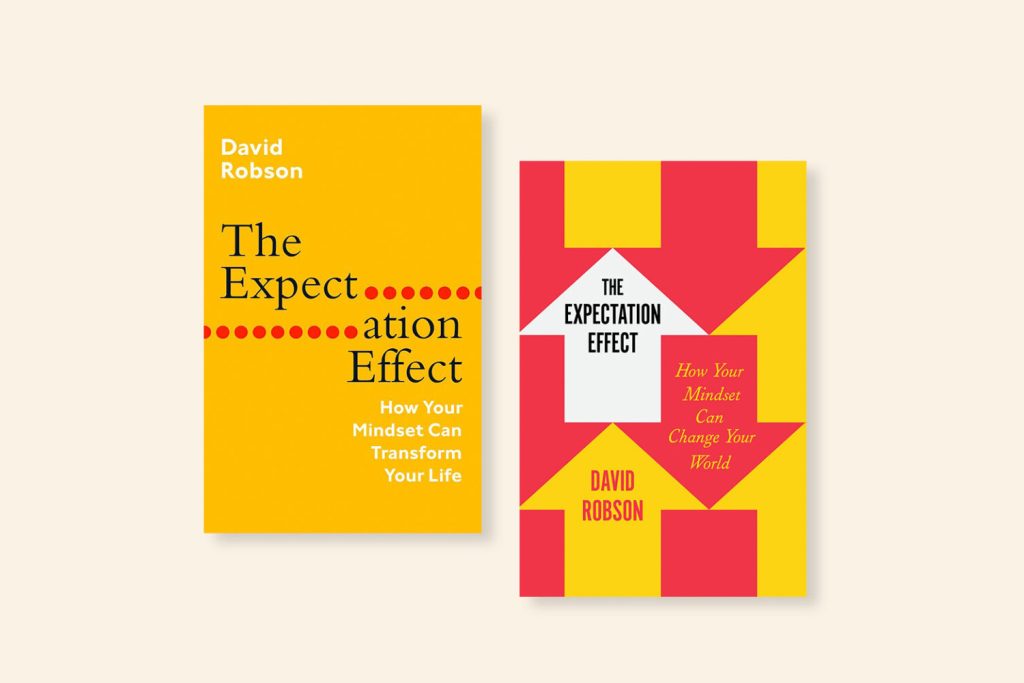

Your Brain Is A Prediction Machine

To understand why the expectation effect filters everything we perceive, we must first understand that our brains act as prediction machines. They are constantly building simulations of the world around us based on context and our previous experiences.

Our brain takes the data hitting our ears, eyes, skin, taste buds and sensors in our nose and makes sense of it by refining it, simplifying it and filling in the gaps. The expectations that come through this prediction machine change what we perceive.

“Seeing isn’t believing. Believing is seeing.”

David Robson

If you want to experience the prediction machine for yourself, look at this picture:

Do you see an ultrasound scan? An Edvard Munch astronaut? Some other kind of Rorschach nightmare?

Most people won’t be able to make sense of the information presented to them here on first glance. But now take a look at this picture:

Now when you scroll back up to the first picture, you should be able to see the adorable dog in the baseball cap. And now that you’ve seen it, you’ll never be able to unsee it – based on your updated expectations, the prediction machine will fill in the previous gaps in your perception.

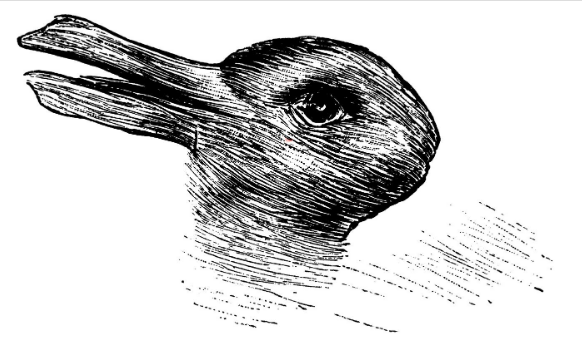

Expectation Shapes Perception, Or How To Tell A Duck From A Rabbit

Look at this famous picture:

You’ll probably either see a duck or a rabbit the first time you see it, and both once you’re told what to look for. But when researchers stood outside Zurich Zoo and asked people what they saw, once at Easter and once in October, they discovered something surprising.

During Easter bunny season, the vast majority of people saw a rabbit – especially children. But in October, they were much more likely to see a bird.

This is because all kinds of minimal cues can shape the prediction machine and what we perceive, right down to the season. This tendency for our expectations to shape our perceptions is really important. In a game of tennis, for example, two players might both be 100% convinced that a ball has either fallen in or out of the court, but no perception is truly 100% accurate: it’s 100% subjective. The same goes for paranormal sightings.

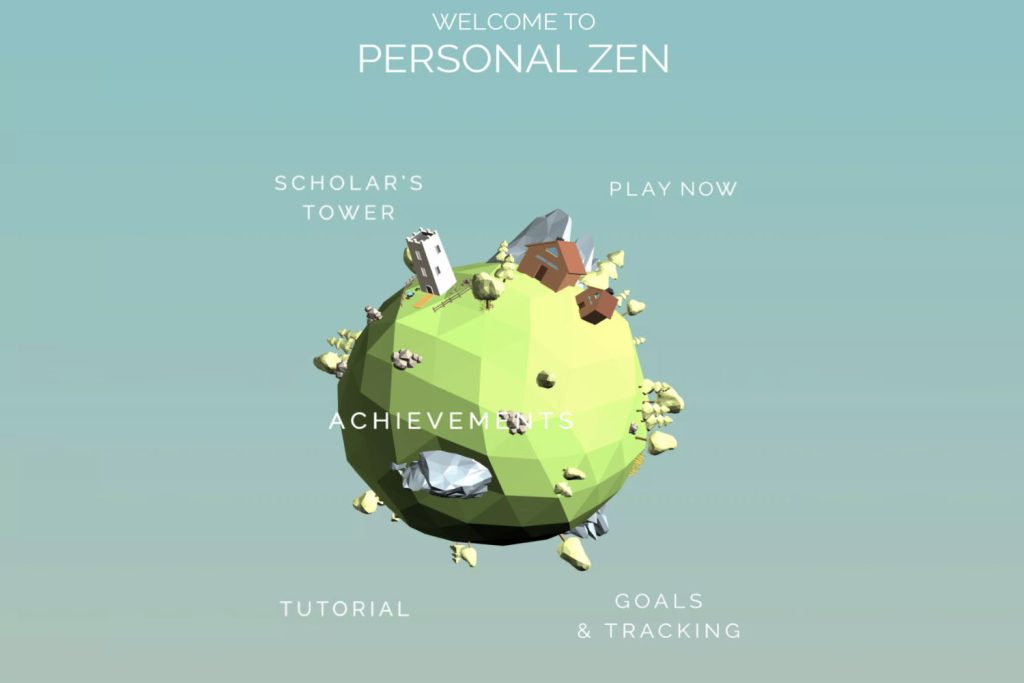

This can also have profound impacts on our understanding of mental health and mood. When people are feeling down, it changes their perception of the faces around them – they are far more likely to see hostile faces, which turns into a vicious cycle that can be very difficult to break.

The good news is that it is possible to recalibrate the attention biases in our brain using simple tricks. A computer game called Personal Zen asks you to pick out the smiling faces on a screen rather than the angry faces, and has been proven to improve the mood of players. So next time you’re feeling glum on your way to work, try counting the smiling faces you see – it might just reset how you feel.

A Beer By Any Other Name Would Taste As Sweet…?

Research shows that our expectations can be tweaked by very simple things, such as names. During an experiment at MIT, researchers went around pubs and bars and asked people to try a new beer called MIT Brew. This was actually a normal beer with one secret ingredient: a few drops of vinegar.

Those who were told this found the beer pretty disgusting – only 20% said they preferred it to a standard pint. But when they weren’t given this information and only had the fancy brand name to go on, 80% said they preferred it.

Similarly, the smell of vomit and parmesan come from the same molecule. The only difference is in how we label it. (Enjoy your next cacio e pepe, by the way.)

Elements like price can also change our sensory perceptions. People in an experiment were given a pair of the same sunglasses. Some were told they were Ray-Bans, and the others that they were a mid-market brand. Those who thought they had the more expensive pair of sunglasses actually performed better in a sight test, making fewer overall mistakes and completing it in 60% of the time.

Marketing Doesn’t Just Change Perception, It Changes Physiology

You’re probably familiar with the placebo effect, which shows that expectations can bring about biological changes, such as blood pressure, inflammation, how quickly you recover from a cold, whether you suffer from periodic headaches, or the level of pain you experience from an injury. Opiods are also much more effective if you’re told they’re expensive and come from a familiar brand, such as Nurofen.

The expectation effect can also alter how we respond to exercising. A study at Stanford University gave people a genetic test before they did an endurance test, looking for the presence of a gene that has an effect on how well we endure exercise. Although the gene test was real, participants were given sham feedback about the results before they took the endurance test.

The feedback totally changed their expectations of the exercise, and therefore also determined things like how effective their lungs were, their endurance, and the release of endorphins afterwards. In fact, it emerged that having positive expectations had more of an effect than possessing the gene itself.

“This is important when talking about experiences, as if we come to an activity with negative expectations about our performance, we’re less likely to experience that high afterwards.”

David Robson

When it comes to food and dieting, our hunger sensors are very unreliable. People with memory loss have been shown to be able to eat a full meal twice in a row without noticing any difference in satiety – something that shouldn’t happen if how full we feel is down to our hunger sensors alone.

Whether we adopt a mindset of indulgence or deprivation is far more likely to affect how full we feel after eating. Another study gave people the same milkshake to drink on two separate occasions. One label emphasised sensory pleasure and indulgence, whereas the other label marketed it as a guilt-free slimming shake.

The participants’ levels of ghrelin – the “hunger hormone” that drops when we’ve eaten a meal – were measured before, during and after they had the milkshake. The levels dropped in those who had the more indulgent milkshake, whereas for those who had the guilt-free label, there was barely any change.

When it comes to dieting, a deprivation mindset that focuses on low calories is probably counterproductive, as you’re more likely to be hungry and snack later in the day. And this sense of indulgence doesn’t just apply to eating, but to everything we do – if we can make going to the gym feel like a real treat rather than a punishment, it’ll be more beneficial for us.

Anticipation is an important part of this, too. Visualising what you’re going to eat in advance can make the actual experience of it even more pleasurable. Perhaps this could also apply to experiences. If we asked people to visualise them in advance, would they get more from it?

Reframe Your Feelings, Reframe Your Responses

Being able to recognise and reframe our feelings can also change our physical experiences. When we experience something new, unfamiliar and important, the signs of physiological arousal are very similar whether we feel excited or anxious about it: we get breathless, sweaty and feel high levels of cortisol pumping through our system. (For more on this, see the concept of “metacognition” put forward by The Uncertainty Experts, who will also be hosting our first Campfire of season 4.)

Likewise, frustration can feel really unpleasant until we see it as a challenge to be overcome and a sign of growth – this might go some way to explaining why Wordle has gone viral. (We could see this as evidence of the importance of flow experiences, where accomplishing something difficult and worthwhile is one of the eight key qualities that define them.)

For the biggest hint that our feelings can be shaped by our expectations, in a study by dating website OK Cupid the site gave couples sham feedback about their compatibility. Those who were told they were unusually compatible were more likely to marry, perhaps because their perceived compatibility made them more likely to persevere and compromise with their partner. And when it comes to ageing, those who believe that it’s a time of growth and wisdom are likely to live 7½ years longer than those who see it as a time of disability and decline.

The Danger Of Over-Promising And Under-Delivering

“What happens when you use the science of expectation and then the reality doesn’t match up?”

Denise Cannon

It seems obvious that we should pump up people’s expectations of an experience in order to improve their experience of it. But could overpromising on expectations backfire if losses tend to loom larger than gains, as we learned in Campfires 48 & 49?

According to Robson, the problem is that people’s starting perceptions are often far lower than they should be. A lot of stress is caused by perceptions that are objectively untrue. So our intervention shouldn’t be to create false positive expectations, but to account for these overly negative expectations, bring them up to a level that counteracts them, and encourage them not to have those perceptions.

If we take an experience like the adult jungle gym Go Ape, some people are going to feel high physiological arousal. If we can convince them that feeling is due to excitement rather than anxiety, they’re far more likely to get more pleasure out of the experience and learn and grow from it. Similarly, if you were designing an escape room, you could try to tell participants that that’s actually the interest of the experience and that it’s an opportunity for growth that they’ll value for months or years to come.

Cannon wondered if the role of the experience designer is to find moments in an experience where there might be an opportunity to feel either anxiety or excitement, such as queueing, and shift the balance.

“The perception of control is really important – letting people feel it’s their choice to be there and even giving them the opportunity to step out if they want to.”

David Robson

Could a level of anxiety be useful in a narrative-driven experience, however?

“I’m not sure we want to completely eradicate anxiety, especially in an experience context, because narrative and story are very important for recall. By flatlining or not having any downs, we risk reducing the impact we’re trying to create.”

Daniel Hettwer

The secret isn’t in eradicating anxiety, but reframing it.

“You want to explain your narrative so they can see that even if they do feel anxious, that might be an opportunity to grow.”

David Robson

(Also see Campfire 25: Beyond The Peak-End Rule, where lecturer Wim Stjibosch explains the importance of painting with a broad palette of “emotional colours”, both positive and negative.)

When using “verbal garnishes”, we still need to be aware of the qualitative aspects of an experience so we avoid cognitive dissonance. As Ron Graham said, “perceptual readiness” is what we want to aim for.

“Expectations can’t work miracles. You can’t turn a plate of lettuce into an amazing banquet – there’s a limit to what you can achieve. It’s about counteracting overly negative expectations – or making sure that people do appreciate positive attributes that perhaps wouldn’t be obvious to them – by changing their expectations, but always making sure that you’re being honest and not getting them to engage in wishful thinking that’s only going to lead to disappointment.”

David Robson

The Danger Of Under-Promising And Overdelivering

We’ve all heard the cliché “under-promise and over-deliver”, particularly in the world of consulting. This might feel like the safer option, and as we’ve heard, we shouldn’t inflate expectations beyond an achievable reality. But could under-promising be just as risky as over-promising?

“Oliver Burkemann wrote about the expectation effect and said that although being a pessimist might mean you’re never disappointed, if perception is shaping your experiences, you might miss out. We should watch out for defensive pessimism!”

David Robson

Perhaps we should prime them to have an open mind where great thing might happen, rather than to have very low expectations in the first place.

Our Campfire also wondered if there are opportunities in negative expectations. Doug Steel was reminded of the success of Banksy’s Dismaland, and Lori Buscaglia had worked on a project where the negative expectation of not being able to get into a popular team’s basketball game was counteracted by creating a new kind of fan experience for those who couldn’t attend.

“I think it’s brilliant to take something we’re familiar with and show us the ugly truth or a different perspective. People come to it expecting to be challenged.”

Steinn

Deliver Expectations, Then Build From There

Perhaps we can use expectations to lead people into an experience with an open mind, before we move them through different zones from comfort, to fear, to learning, and eventually to growth.

“At the beginning of my experiences I usually give them what they’re expecting, so they lower their internal barriers, feel safe and heard, and have an open mindset where they’re more courageous. By the end, they’re doing things they absolutely thought they wouldn’t do.”

Pigalle Tavakkoli

The WXO Take-Out

Once we understand the science of the expectation effect, we can use it to change the experiences that people have.

- Price and branding can influence perception and physiology, from how tasty a glass of wine is to how effective a painkiller is.

- Expectations of luxury can enhance an experience. By adopting a mindset of indulgence, we get more out of an activity.

- Verbal garnishes can transform what someone sees and tastes. Remember that MIT Brew beer, or vomit vs parmesan.

- Many emotions are ambiguous – and we can help people to reinterpret them by encouraging them to frame them in a way that helps them to learn and grow from an experience, rather than remaining stuck in the fear zone.

Want to be part of the most inspiring experience conversations in the world? Apply to become a member of the World Experience Organization here – to come to Campfires, become a better experience designer, and be listed in the WXO Black Book.