A train that leaves bang on time. A roast dinner on Sundays. The contents of your Christmas list. We all love getting exactly what we want, right?

And when it comes to experiences, there’s also nothing wrong with delivering on our audience’s expectations. An experience can be entertaining, satisfying and fun, without pushing the boundaries of what people want.

However… what if you could go one step further – and as well as giving your audience what they want, you could inject their experience with a secret kernel of meaning? Something provoking and unexpected, which not only challenges their idea of what the experience should be and makes it far more memorable – but also changes their very sense of self?

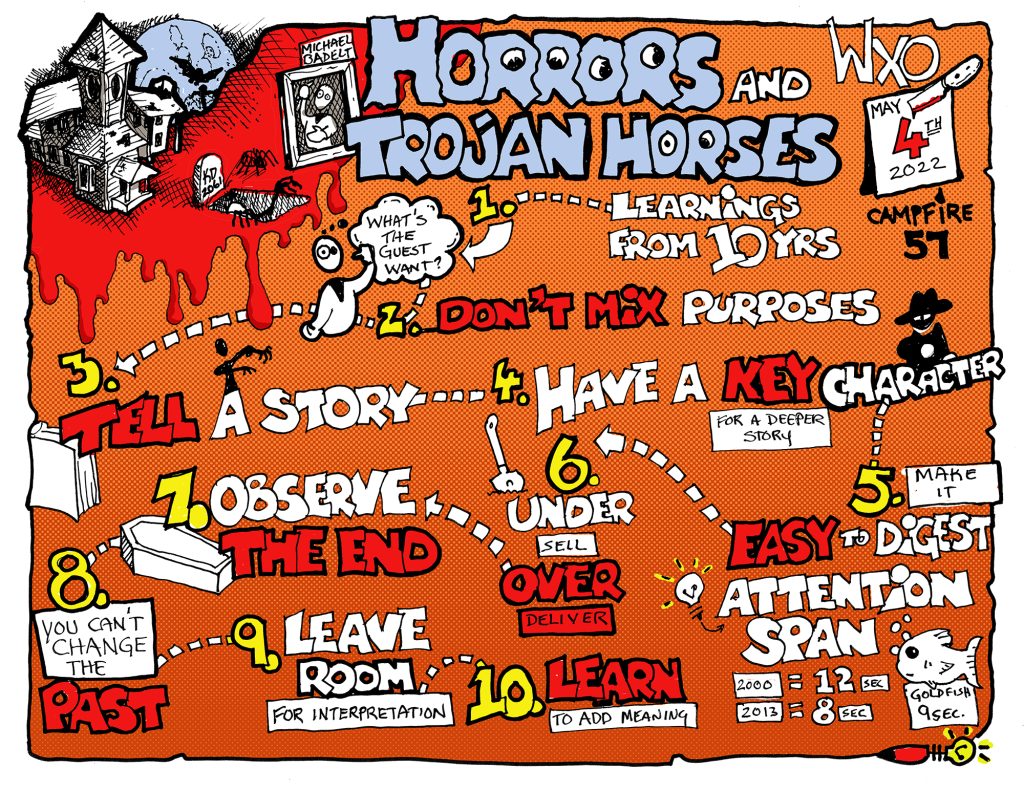

Frankfurt-based horror attractions designer Michael Badelt, who has 22 years’ experience in the theme park industry, believes that there’s a huge amount of untapped potential to infuse experiences with an underlying narrative or meaning for your audience to discover – a technique he calls the Trojan Horse.

“When it comes to making an attraction scary, the parameters of the experience often depend on the creator’s understanding of what their target audience might want. Sadly, this leads to designers underestimating their audience – resulting in a fun experience that lives up to expectations, but doesn’t have much depth.”

Michael Badelt

Instead, through a test-and-iterate approach to a live horror experience he created in a German theme park, Badelt has developed a framework for delivering both cheap thrills and deep transformation.

And whether you’re designing haunted houses, theme parks, or something entirely different, we think his method for delivering meaningful thoughts that will *haunt* audiences long beyond your experience ends is *frighteningly* relevant to all experience designers looking to tantalise, tease and transform.

Selling Drugs And Stereotypes

When you think of Halloween horrors, what comes to mind?

Is it a haunted house? A creepy character pouncing on you from the shadows? Or perhaps a melting Scream mask (how 90s of you)?

If so, you’re probably not alone. They’re all iconic trademarks of Halloween attractions, alongside chainsaws, corny jokes and a dash of political incorrectness.

These stereotypes aren’t necessarily a bad thing. They’re part of the expectation, both for the designer and for the guest. They also allow us to create a rush of hormones like dopamine or adrenaline – Badelt once attended a horror attraction seminar with the title “I’m selling drugs”, inspired by the chemicals that such cheap thrills can produce.

However, when we rely solely on stereotypes, the content we produce can feel quite shallow. All of which led Badelt to wonder: is this all there is?

Close Encounters Of The Guest Kind

To confound our guests’ expectations, we first have to understand what they are. Guests will have a set of “active wants” – things they are seeking from your experience – as well as “don’t wants”.

In the haunted house space, for example, the “wants” might include jump scares, laughs and cool costumes; whereas the “don’t wants” might include waiting in line, making a fool of themselves, or having to do a lot of thinking or make complicated decisions.

We also need to consider the context our relationship with our guests exists within. The battle for their attention is real.

In 2000, the average human attention span was 12 seconds. By 2012, this had shrunk to 8 seconds. By comparison, the attention span of a goldfish is 9 seconds. (Want to regain control of your own attention span? Check out Campfire 51: Indistractable! With Nir Eyal.)

Based on these factors and his experience of designing attractions, Badelt made the following assumptions about guests’ behaviour:

- People are bored much more easily with long-form entertainment than they were 20 years ago

- “Active thinking“ and use of “common sense“ are seemingly being discouraged by society and lawmakers

- Society appears to have become more and more superficial

- People want easy to digest and easy answers, while claiming to be interested in the whole story

- People get angry when being forcefully separated from their phones for a prolonged period of time

- People often assume you don’t care and are only interested in making money

These assumptions might seem sad – but they’re the reality of the environment we’re working within. So how can we create experiences that work within these confines, while still challenging guests and giving them more than they expected?

The Making Of A Trojan Horse

Around a decade ago, haunted attractions started to diversify, experimenting with different approaches like theatrical storytelling, blacklight and extreme violence.

Amid this landscape, German theme park Fort Fun Adventure Land challenged Badelt to come up with a new horror attraction, which he named Fort Fear Horror Land. The attraction evolved over time, as Badelt tested, experimented and tweaked based on learnings from the audience.

Evolution 1: Badelt and the event’s design team started by developing a backstory and a properly designed and motivated main character. They even turned the story into a novel that you could buy online as a kind of Easter egg.

Evolution 2: The second step was to experiment by adding a layer to an existing attraction by sending in guests alone and into pitch black, with just a torch for company. The twist was that the torch was remotely controlled by Badelt’s team, who could make it flicker, vibrate, change colour or switch off. The result was that guests would feel the attraction rather than just see it, entertaining without traumatising.

Evolution 3: Badelt amped up the stakes by creating a full alone-in-the-dark attraction that used mind tricks to create suspense – after all, the greatest tool for an experience designer is guests’ imaginations. Each scene was designed to trigger at least 3 common phobias, and staff were trained to carefully touch guests to guide them through the experience.

This phase of the experiment was successful – it sold out and the premium ticket prices weren’t an issue, as the experience had a high perceived value. The reaction of guests was also largely positive, ranging from giggles to sheer terror to discussions about the meaning of life.

However, it also threw up some problems. Badelt had accidentally created a serial exposure therapy experience, where they needed to give guests a safe word in case it became too much. The narrative was picked up, but the storyline wasn’t. And the experience was so extreme, it hit a dead end: there were limited opportunities to amplify it, particularly in the setting of a family theme park.

Evolution 4: Badelt decided that the path forward would be to go backwards by dialling things down a notch. The experience would become less extreme and more family-friendly; the storytelling would become more focused; and there would be greater guest interaction.

He and the event’s design team came up with the concept of “The Hotel”, set in the American West in the 1900s. In this first iteration, they designed an evolving story with interactive branches, including social topics like vanity and honesty in the narrative, and added escape-room elements.

Unfortunately, they discovered that people who have been promised a haunted attraction don’t like to solve puzzles, as the mindset is different.

In an escape room: “I need to solve puzzles and they’ll scare me to distract me.”

In a haunted attraction: “I will be scared and they’ll distract me with puzzles.”

Evolution 5 (The Trojan Horse): To counter this, Badelt removed the majority of the puzzles and changed the marketing from “haunted house with escape-room elements” to “haunted immersive experience”.

He also added another ingredient that turned out to be the key to the experience’s success: during one part of the story, guests were split up and given something to eat or drink. They later found out that the cook may have poisoned it, and were given a moral choice whether to do the same for the guests who came behind them. The script for the finale then changed based on the choice they made.

This tweak ended up being the thing that made the attraction really click. Guests would leave the experience and start applauding. They engaged in intense debate with each other about whether they had made the right choice. And most importantly, they took more away with them than they had bargained for, learning something about themselves in the process.

Question Your Guest Assumptions

Through this gradual process of listening to feedback and evolving his experience accordingly, Badelt learned that his original assumptions about guest behaviour weren’t entirely accurate.

He’d assumed that theme park audiences weren’t open to narratives with deeper meaning. However, it turned out that in fact they were – as long as they had been primed to receive them with the right marketing, weren’t being existentially threatened, and the time had been taken to build a level of trust so they were in a state of open-mindedness.

The assumption that guests, with their sub-goldfish attention spans, wouldn’t get anything that lasted longer than a few seconds was also proved wrong. If you tell them how long it will take, remove distractions and make it personal, you can hold their attention for a much longer period.

How Do You Build A Trojan Horse?

From all of this experimentation, Badelt was able to identify some key actions that helped create a Trojan Horse experience. Although these are specific to the attractions world, we think they could be used across a number of sectors. He:

- Listened to guest feedback, camping out at the exit to overhear unfiltered conversations as well as asking them what they thought.

- Promised a light, story-based, immersive experience that was non-threatening.

- Gained trust through the way the actors engaged with guests.

- Pulled the audience into the story and underlying narrative.

- Gave them a sudden confrontation with a moral choice that was retroactive, emotional and based on reciprocity.

- Delivered on the promise to entertain…

- …but over-delivered in meaning.

From doing this, he was able to define a Trojan Horse as “a key element of an experience, elevating it to something meaningful.”

Used correctly, a Trojan Horse:

- unlike its origin story, should only be used with positive intentions

- quietly enriches an experience rather than being on the poster. If it were, the targeted audience would be very different and have different expectations

- has room for interpretation and intentionally leaves questions unanswered

- does not take the moral high ground. Instead, it leaves it to the guest to decide

Think of Meow Wolf, and the way it’s quietly able to engage those who think they don’t like art in participating in an art experience. Or Punchdrunk, who use fear, thrill, uncertainty and anxiety to create an unforgettable experience. Or how audio description in galleries can be used not only to enrich the experience for the visually impaired, but also increase the attention span of sighted people.

Why Moral Dilemmas Make Us Feel Alive

Perhaps one of the reasons that posing a moral dilemma is so crucial is because when we’re asked a question that has no clear answer, wherever we land is a reflection of our own character. By being forced to work out what we think about the question, we also have to work out what we think about ourselves.

“Sometimes we are unaware of our own position and true opinion of something, so moral dilemmas engage us in an inward dive that is very captivating, engaging, and in a way transformative.”

Lina Edris

Harsh Manrao suggested a framework for creating situations that lead to moral dilemmas, based on the following three principles:

- Violating the principle of reciprocity, i.e. doing something to someone else that I wouldn’t want done to me.

- Incentivising for the greater good, i.e. doing something bad, but which might have a positive effect for the majority.

- Asking them to do something they wouldn’t want to tell their mother, i.e. doing something that feels good but would make me look bad if people knew about it – such as evading taxes or gossiping – and therefore comes with a thrill attached.

“Once you have this framework, it’s very simple to ask: what kind of dilemma do I want to create? And the choices themselves become binary, because there are set rules around what people would do.”

Harsh Manrao

At Ghost Town Live at Knotts Berry Farm, for example, theme park guests are given a series of moral dilemmas to make throughout the day. They are asked who they want to be the mayor – the existing mayor (good), or the head of the bandits (bad)? Children are made assistant sheriffs and given the choice to arrest someone or not. And guests can choose to convey messages between star-crossed lovers or not.

“It’s an incredible moral choice and such a complex storyline. There are so many ways to tell a story and invite your guests to participate. And as there are no universal morals, these are passionate decisions.”

Cynthia Vergon

Being Given Permission To Fail

Having a partner who is willing to let you iterate and problem solve in the way that Fort Fun Adventure Park did with Badelt is crucial in identifying what the Trojan Horse in your experience could be. This was certainly Justin Stucey’s experience when working on Meow Wolf’s Convergence Station.

“What I think is really awesome is that you had a partner that was willing to go on this journey with you to test, evaluate, refine, and commit and build your audience and program. In the case of Meow Wolf, we were problem solving every day – but as a result, we ended up presenting questions in a way that they were not perceived as problems.”

Justin Stucey

At the WXO, we absolutely believe in the power of partnership to solve problems, which is why we’re dedicated to finding ways that experience designers from different sectors around the world can connect, collaborate, and give each other the space to experiment and identify new solutions. (See Campfire 55: 3 Passion Projects for an example of this supportive network in action.)

The WXO Take-Out

Badelt’s horrifying case study is a masterclass in how in order to create transformation, you can’t make it happen: you can only create the conditions that allow for it to happen.

“Experiences are co-created. You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make it drink. All we can do is create the stage and the suggestions for the experience to happen, so we’re not so much designing transformation, as we are designing for transformation.”

James Wallman

(For more on designing for transformation, don’t miss Campfire 58: The “New You” Business With Joe Pine.)

When it comes to designing your next experience, consider:

- What assumptions are you making about your guests? How could you challenge or test them?

- What emotion or transformation do you want to design for?

- Where could you insert a moral dilemma into your experience?

Want to be part of the most inspiring experience conversations in the world? Apply to become a member of the World Experience Organization here – to come to Campfires, become a better experience designer, and be listed in the WXO Black Book.