How does the commercial inform, inspire, and change the creative of an experience?

Understanding how feasibility and creativity can work better together puts us in a stronger position to build sustainable experiences that last longer – and make more money.

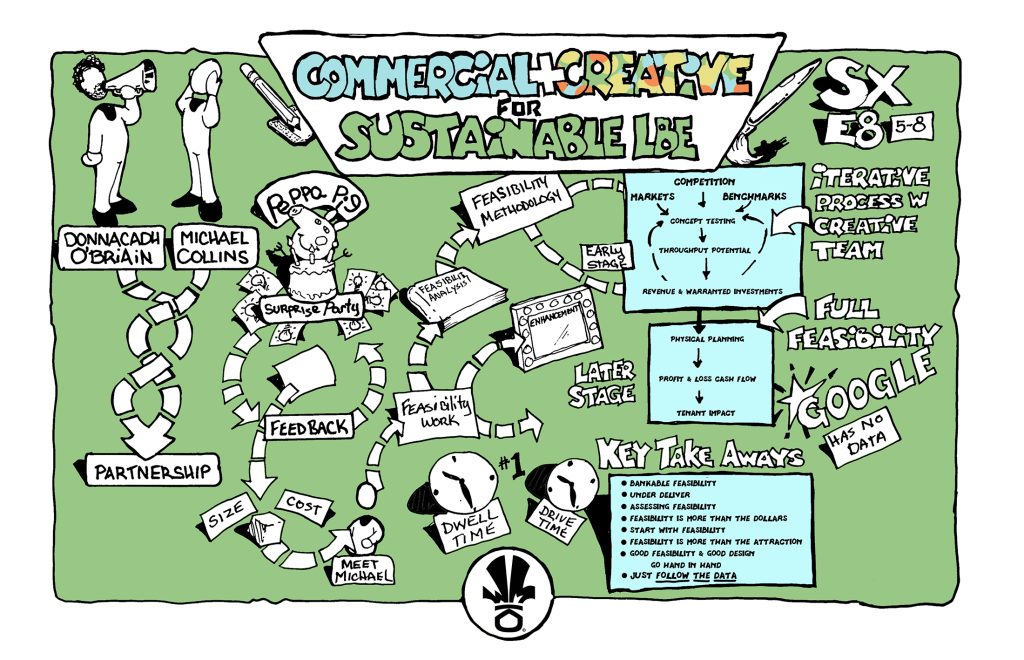

So we brought together Donnacadh O’Briain, Creative Director & Story Architect (The Creative), and Michael Collins, Senior Partner at Leisure Development Partners (The Commercial) for a frank discussion on the tensions between the two in LBE and the attractions industry, plus how you can navigate them in your next experience.

The pair recently worked together on Peppa Pig: Surprise Party, a new immersive experience aimed at families that is still in development by The Everywhere Group, the company behind immersive productions of Peaky Blinders, Doctor Who and Gatsby.

O’Briain and Collins share how the collaboration came to be, what the feasibility process for an experience might look like, and the main tensions to watch out for when embarking on the journey, so you might better understand it when starting out on your next experience.

The Creative Process Before A Feasibility Study

To set the scene for what the process for Peppa Pig: Surprise Party looked like before Leisure Development Partners got involved, O’Briain broke it down into a few steps.

- Creative prompt. At this stage very little was known, from the number of actors to the exact square footage, except some reasoned estimates. O’Briain and the show’s creative director began meeting to try and figure out what the show might look like.

- First draft. A couple of pages of creative ideas, not really thinking about the numbers.

- Visiting the license holder. They then went to Hasbro to test their ideas for scenes, setups, characters and journey, getting feedback to guide the next steps.

- Second draft. They began building the show on paper, from which characters would be there, which rooms would be used, what children would do in the space, how parents would be integrated, and so on. After presenting this, they began working with a designer to put some pictures together.

- Present to producers. At this point they were told to reduce the scale by 25% and the actors to 6 people.

- Third draft.

- Feedback. At this stage they were told to bring down the space and cast size once again as well as the audience size, as well as figure out how to squeeze extra numbers in at peak times by playing with a wave structure and adding actors for those times.

At this point they were still looking at venues and a new design team was brought in. The Everywhere Group were looking to move away from a single director model, more associated with traditional theatre, and towards a design company model, more associated with attractions. The new design team wanted to work with Leisure Development Partners (LDP), which is where Collins came in to engage on a new creative process.

Great Feasibility Enables Great Creative

“I want to dissipate that there needs to be tension between creative and commercial: it should be collaborative. My job isn’t to pour cold water on brilliant ideas or crush dreams – it’s to optimise and make sure things work. We want to make sure the attraction will please people for years to come.” – Michael Collins

LDP’s work is on bankable analysis. This can mean hardcore ROI to take to investors or banks, or giving certainty to stakeholders, whether that means the team or the venue, that an experience will work and continue to work. LDP tracks the accuracy of what they do through metrics like attendance and ticket sales, with 90% of projects falling within the projected attendance range. Those that don’t have often spent no money on marketing or slashed their budget by a huge amount. Everything is driven by benchmarking and data.

The company covers not only specialty attractions or theme parks, but also water parks, brand centres, museums, heritage assets like St Paul’s Cathedral or the Eiffel Tower, movie studios, FECs, brand experiences, licensing IP for a permanent experience, pop-up facilities and events and so on.

Common Misconceptions About Feasibility

Collins outlined some classic misunderstandings that arise when talking about feasibility.

- Build it and they will come. You need to look at actual markets and opportunities, and help scale projects to those markets.

- My experience represents everyone else’s. People tend to think about what they paid last time they went to an experience, rather than about affordability for the market. Different people have different access to cash, so you must remove subjectivity and look at how people really behave.

- People in my country or city behave differently. There are regional differences, but people do behave in relatively similar ways – so we can learn from one market and apply to another.

- I’m not really concerned about ROI, so feasibility doesn’t matter. Feasibility isn’t just about money, it’s about marrying what you’re doing to consumer demand. It’s about providing the right footprint, capacity, and programming – not in terms of the story, but in the demographics and demand. Take dwell time, for example – it’s useful for the creative team to know early on whether it’s best to go for a batched model or an open-world experience based on how long people will stay, how they will engage, and how much money they’ll spend on F&B and merchandise while there.

The Disney-Approved Feasibility Methodology

In the 1950s, economist Harrison Buzz Price invented a methodology for Disney that LDP still uses today – with the advantage of great data, opposed to the blank database Buzz Price was working with. What’s required to give an understanding of a real business isn’t guesswork, but a methodology that relies on benchmarking and that works.

This methodology covers two main areas of analysis:

- What should you build (physical planning analysis – marrying up from the markets to work out how many people are we designing for on a typical day and what capacity do we need for them?)

- How will it perform (attendance and financial forecasting – how many tickets will you sell and what does that mean for revenue and operating profit?)

The first part is what creatives are typically looking to get hold of, as it gives them footprints, budgets, and an idea of how many people they’re looking to design for.

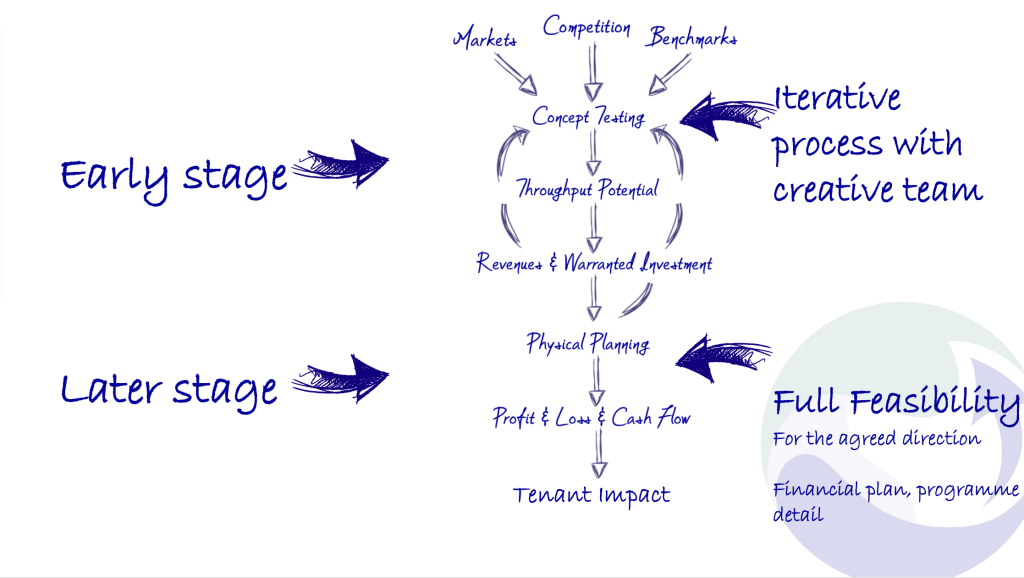

The Typical Feasibility Process

This process starts with three areas of research: markets, competition, and benchmarks.

These all feed into concept testing, looking at throughput and ticket sales, where feasibility really needs to bounce back and forth with creative, and should be anything but tense. Profit and ROI aren’t everything – the impact could also be in creating economic impact, jobs, driving tourism, and so on. Ultimately this surplus drives the reinvestment and keeps the experience alive.

This is the part when the process tends to highlight things that aren’t perfect – e.g. CapEx is too high, demographics aren’t quite right, or ambitions are too modest. These learnings cause a bit of rethinking and optimisation to figure out how to to grab people’s attention for longer and allow for a bolder ticket price. This pre-feasibility stage might be 3-5 weeks, or 3-5 months, depending on the project.

When it came to Peppa Pig: Surprise Party, this stage highlighted that in order to access the footfall needed for the venue, they would need to pull in audiences from a wider area. This meant they needed a longer dwell time than initially thought, so the focus was on making the experience something they would want to stay in for longer rather than a batched, 60-minute run time.

“We re-envisaged how the experience physically worked, how the audience went in, how they moved around, how the story moved around them. We then went back to LDP, but also to the licensor – so there was an interesting process of back and forth in getting that right.” – Donnacadh O’Briain

People Are Predictable: Why Benchmarking Works

People always think their city or market is different, and assume that their experience will break all the rules. But this always turns out to be wrong: people are predictable and behave in similar ways.

Take drive-time catchments. People don’t like driving for longer than the experience they will have, so getting people from a secondary market to visit likely won’t result in huge numbers. By making the experience longer, you can also push the ticket price and give people better money value for time.

“There are patterns in the data that we look at, and those patterns are really valuable when trying to assess the realistic expectation for feasibility.” – Michael Collins

Benchmarking is the key to good forecasting. The kind of benchmarks that go into a typical feasibility study include:

- Market penetration

- Peak on site

- Length of stay

- Sponsorship

- Utilities

- Hourly capacity

- Per capita spends

- Reinvestment

- Insurance

- Marketing

- Staff metrics

- Repairs

- Yield

- Attendance

- Seasonality

- Per capita spend

- And so on!

There’s no published data for any of the businesses we’re talking about: LBE, theme parks, etc. LDP gathers and hoards all this data by talking to people. Most people don’t know the answers to these KPIs, but we can tease it out and tell them how they’re performing compared to their peers.

Examples Of Benchmarking In Key Performance Indicators

Attendance: LDP looks at market penetration rates – the proportion of their available market that visits annually – and uses that to forecast.

Pricing, yield and spend: when people do their business plan, they think about what someone will spend on an experience at peak time. They don’t think about off-peak times, or concessions, and everything else that chips away at the average ticket price. LDP benchmarks and looks closely at yields. 50-60% yield is not atypical for LBE, but can be difficult to swallow for producers.

Design & master planning: you need to understand and design for the average busy day. Not for the absolute peak, as you’ll put in too much capital, or for a day where there’s no atmosphere and you’re the only customer. It’s about finding the balance and thinking about things like how many parking spaces you’ll need, how people will get there, how many seats you need in your restaurant, whether it should be table service or kiosk, etc.

The WXO Take-Out

Collins left us with a few key takeaways:

- Bankable feasibility can’t be conducted by generalist consultants with no data or industry experience.

- There’s a tried and tested way of assessing feasibility for attractions that works.

- Feasibility isn’t just about money: it’s about demographics, CapEx, scale, capacity and so on. The job of the commercial isn’t always to reduce those things – they can also spot opportunities to be bolder.

- There are many things that people spend on in an experience that we can look at – hotel beds, meals, retail, etc. We should also work out how much of this spend can be captured by the people originating the idea.

- Even if you don’t need ROI, you still need feasibility to scale your experience correctly so it’s not too packed or completely empty.

Naive optimism may be an essential part of being human, and most things may fail. However, the power of the feasibility study is in focusing us on the opportunities available, and helping to avoid as many of the pitfalls as possible.

So next time you’re designing an experience, ask yourself:

- What market are you designing for? Is your current experience taking into account what it will take to attract that market?

- What benchmarking data could you draw on to inform your creative?

- What does your current feasibility process look like? Could it be improved?

Want to come to live Campfires and join fellow expert experience creators from 39+ different countries as we lead the Experience Revolution forward? Apply to join the WXO today.