Could it be magic… or experience design?

Dive into an exploration of how magic theory intersects with experiential design in a lecture presented by Curtis Hickman, the driving force behind The Void‘s standout experiences and the author of the critically acclaimed book, ‘Hyper-reality: The Art of Designing Impossible Experiences‘.

Hickman’s grounding in magic design and illusion started at the age of 13, when he met a magician called Danny Haney who became his mentor, introducing him to classical books on magic that helped him understand not only how a trick happens, but the “why”. Specialising in mystery and miracle, Hickman’s passion for the craft found a new home in visual effects and VR because of its ability to transcend the limitations of reality.

This foundation became a big part of The Void, the deeply immersive VR experiences Hickman created under the umbrella of “hyper reality”. His background in digital and practical illusion design led to the development of the fundamental technologies behind these experiences. He was the executive Creative Director of nearly every Void experience, including “Star Wars: Secrets of the Empire” and “Ghostbusters: Dimensions”.

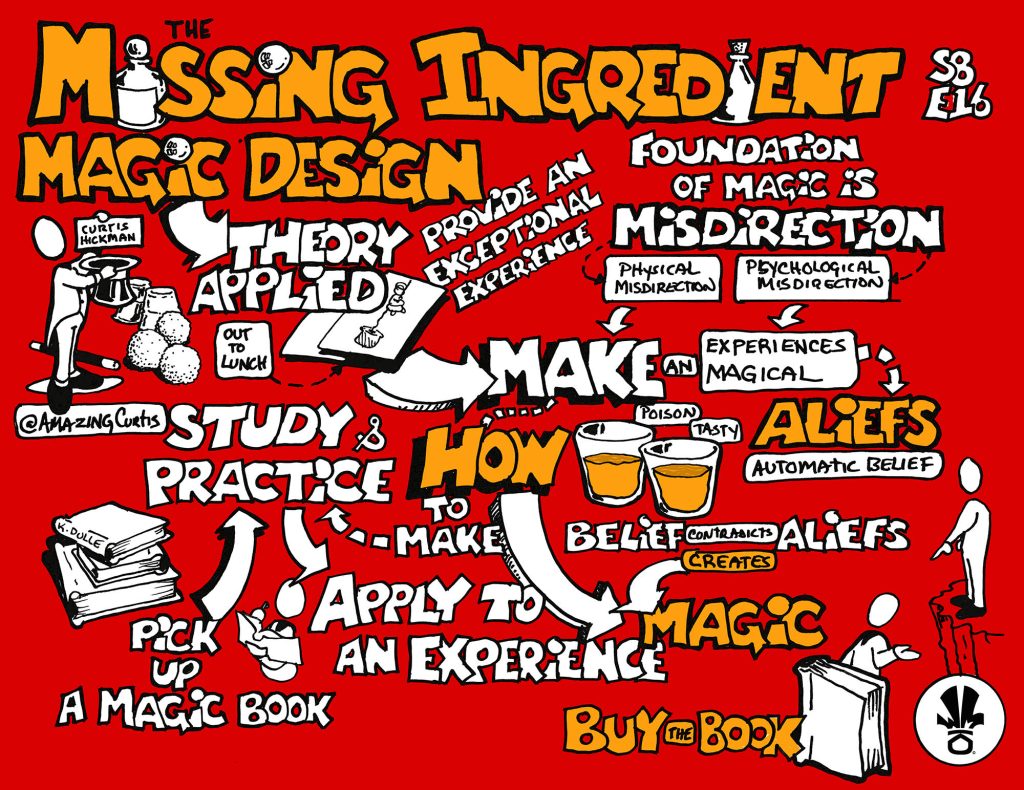

This session will shed light on the principles of blending magic with design, supported by real-world examples. Drawing from a wealth of firsthand experience and previously undisclosed insights, you’ll leave equipped with a nuanced understanding at the forefront of innovative experience design. You’ll learn:

- Why misdirection is the foundation of magic design

- How to use concordance and “aliefs” to create exceptional moments

- How to apply magic principles to your next experience

Ready to add some abracadabra to your experiences?

All Experience Is A Narrative Event

Hickman was inspired by former Disney Imagineer Joe Rohde’s thoughts on the concept of experiences:

“Experience is a record of relationships. Relationships between things that happen in the world, your body’s reception of the impulses created by that thing that happened, and the formation in your brain of the story you tell yourself about what happened. Since the last part of that sequence is the main part you are aware of, that means experience is a narrative event. It is what we tell ourselves happened.

Our brain is a predictive organ. In order to save on reaction time and the expenditure of energy, it creates models and scripts, which are used to anticipate what’s going to happen, so that we can react and survive. This means that in many cases, the brain model circumvents any actual experience of the real world at all.

You could go out to dinner, sit at a table for an hour, walk away, and five minutes later be unable to describe a drinking glass you used for the entire evening. Because you never really experienced the glass at all, only a reasonably usable behavioural model called ‘restaurant drinking glass’. So! If you expect to create a memorable experience, you must at the same time provide an exceptional experience.”

Joe Rohde

The core of experience design lies in this concept: how do we get people to create meaningful stories that they’re going to remember? Hickman believes a great tool to make exceptional experiences is magic.

Take that drinking glass. People might remember it if it was a fancy glass with frosting and embellishments. But what if it had some magical properties? What if it refilled itself throughout the evening? Or changed colours or shape? Or disappeared or reappeared or went through the table? What if the glass had magical properties that you interacted with as part of the evening? Suddenly that glass goes from being something that you forget to something that you tell people about for the rest of your life.

You have to figure out what the story of your experience is. Maybe you don’t want the experience to be all about your drinking glass. This is, of course, just an example of how you can take something that people would immediately forget and turn it into something that they will tell their grandkids about someday.

“There are magical performances that I did decades ago where people will talk to me about how they became a story that they would tell other people. I love that, because great experiences aren’t about necessarily telling stories to guests, but having guests live stories that they then get to tell others.”

Curtis Hickman

The Foundation Of Magic & The Art Of Misdirection

While there might be some debate among magicians as to the foundation of magic, for Hickman it’s simple: the answer is misdirection. However, he believes that the way the everyday person thinks about misdirection isn’t the same as the way magicians think about it. It’s not about yelling “look over there!” or disappearing assistants in a big puff of smoke. Misdirection is not about directing wrongly or distracting.

A magician would define misdirection as that which directs the audience towards the effect and away from the method. This misdirection breaks down into two categories:

- Physical misdirection: controls how information is received.

- Psychological misdirection: controls how that information is processed or perceived.

Take a magician floating a ball on stage. When you see this, you think “there must be something holding it up”. So the magician takes a ring and passes it over the ball to prove there isn’t. This is where you run into magic: the moment where you can’t understand how the trick is working against everything you understand about gravity, physics and reality, creating a moment of astonishment.

This also correlates with Joe Rohde, who breaks experience down into the same two elements:

- The inputs you receive from an experience.

- The story you tell yourself about those inputs.

Magic is inherently exceptional because it’s an exception to the usual order of events, and so it’s something that you can remember because you witnessed it. In really good magic design, you won’t only have witnessed it, but felt like you were part of making it happen.

Based on these principles of misdirection, you can ask yourself:

- What am I trying to convey? What’s the effect I’m trying to achieve?

- How can I take people away from the method of how I achieve that, and point them toward the effect itself? How do I use physical and psychological misdirection to push the effect of my experience forward, and hopefully make that concept feel more incredible, exceptional, memorable, and a story worth telling?

How To Create Concordance

A lot of people perceive magic in a glitzy, Vegas kind of way: playing cards, capes and other cheesy forms of presentation. But we can take the old theories of magic and apply them to experiences to make them feel magical without literally using tricks or gimmicks.

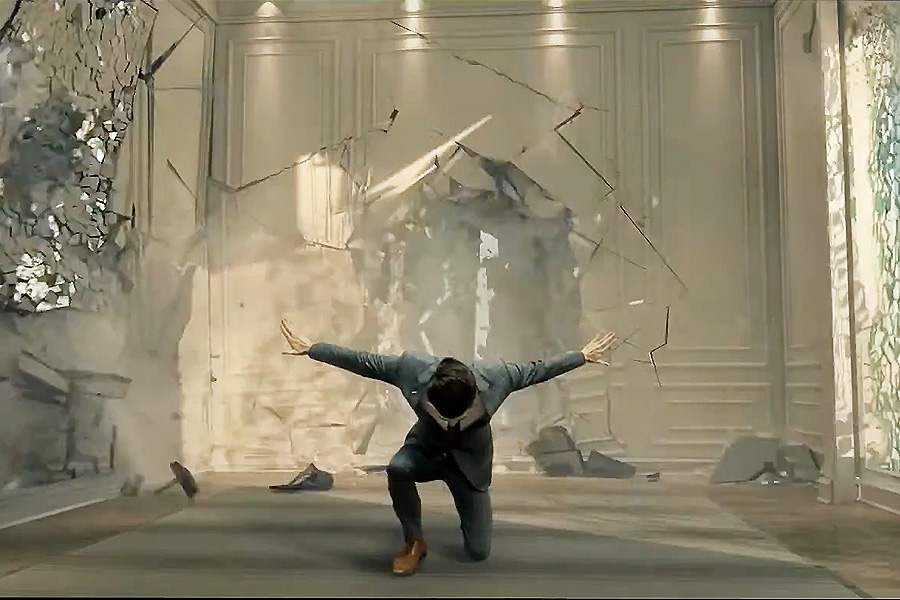

TV host Jimmy Fallon attended The Void’s Ghostbusters: Dimensions experience, and later talked about it on The Tonight Show. Fallon describes his experience the same way someone might describe a magic trick: “unbelievable” and “incredible”. He describes the experiential moments – those little stories that he had throughout the experience – and they become a memory of an impossible event that he lived in the Void.

Hickman and his team did everything they could to try and make that impossible moment as real as possible through VR and sensory effects, to create arguments in the mind that what guests were seeing and doing was really happening. In other words, they treated everything like a magic trick.

This concept is called “concordance”: that if all your senses are agreeing with each other that something is happening, you’re going to believe it. And not only believe it, but alieve it.

Taking Advantage Of Aliefs

An “alief” is a concept defined term coined by Professor Tamar Gendler. It states that people have beliefs, the things they believe in actively, and then they have aliefs, which are things that they believe in automatically.

An example of aliefs is if you have two cups of juice, one labelled “poison” and the other labelled “delicious juice”. Unsurprisingly, people will drink the delicious juice. But if you have them make the juice and put it into the same two glasses, they’re still far more likely to drink the one that says delicious juice, even if they know they are both juice. This is because they have an alief system that says drinking poison is bad. It’s good that we have this belief system, as it helps protect us. But if we know about these automatic beliefs, we can also take advantage of them.

Going to the movies is another example of this concept of suspending your disbelief. There’s an active suspension of disbelief where people can understand that something isn’t realistic, but let it go. But there’s also the automatic suspension of disbelief, where you’ll feel scared if something frightening happens on screen, or you’ll feel for the characters.

In a final example, a group of scientists took a block of fudge and put it into a dog-poo shaped mould or a fudge square. People were told they were both fudge, but would choose the one that looked like a square. But if they had to eat the other one, and they knew it was fudge, it was still an extremely uncomfortable process for them because there’s something inside that tells us this is a terrible idea.

You can take this concept and create belief-discordant aliefs: the idea that when you have a belief and an alief and they contradict each other, you can create a magical moment. A good example of this is the example of heights. In The Void, Hickman often used heights as a way to quickly immerse people into an experience. People would try and get used to the rules of this new digital world, so Hickman would get them to physically interact with things in order for their alief system to reattach itself and say that things that are digital here are also physical.

“People very quickly got comfortable with the idea of leaning on digital walls, which in a normal virtual game is a really bad idea. But in The Void, they would get used to it and their alief system would connect to it. And then they’d step out onto the edge of a cliff that’s very narrow and had a huge drop off. And they’d get scared. It created a great vista, but it also created this tense moment.

They couldn’t help it: this fear of falling to your death is an alief system that is embedded into us. Even people that are seasoned at VR are still not comfortable with heights in VR. So now I’ve skipped over the part where I have to get them to believe that they’re in a virtual world, because they alieve it.”

Curtis Hickman

This is a belief-discordant alief because you know that you’re perfectly safe, but you also feel like you are not. And that is fun, as per the old Imagineering philosophy that danger minus the threat of death equals fun.

People think that playing with aliefs just means subverting expectations. An example of a belief-discordant alief would be dropping something to the floor and watching it fall, then picking it up and dropping it a second time and it floats. This subverts your expectations and goes contrary to your alief system, creating a magical moment. However, not all subversion of expectations is good. When you start breaking contracts with your audience, or start pulling them out of the experience, you can damage it.

Top Tips For Magic Design Novices

Understanding how to apply magic to the design of your experiences starts with study, and learning the “why” of magic. Hickman recommends the following books:

- Experiencing The Impossible, Gustav Kuhn

- Designing Miracles, Darwin Ortiz

- Strong Magic, Darwin Ortiz

- Hyper-Reality, Curtis Hickman

But once you’ve learned some magic theory, how do you get it out into the real world?

Hickman suggests getting a beginner’s book on magic or going on YouTube and learning some tricks, especially beginner’s magic. Then try and take the principles of that trick and apply it to an experience, whether theoretical or one you’re already working on.

Take the “Out To Lunch” principle, an old classic in magic that was marketed back in 1947. An initialled business card with a picture on it (originally a boy climbing a rope) disappears and in his place is a sign saying “Out To Lunch”, still with the original initials. The principle is very simple: it’s got a covering on it that gets taken off when the person takes the card, and they don’t realise they’ve actually signed a card that’s been previously marked.

So what could we do with this? Hickman suggests some examples:

- In a game of “murder in the dark”, participants sign a card and fold it, and when they open their card the murderers have a skull on it.

- At a seance, people sign a card or their ticket and later on, there’s some ghost writing on it.

- A spy moment in an escape room, where there’s a code at the top of a card and when people pull it out to punch in the number for the safe, it’s got extra writing on it. You could even make it so that the code doesn’t work, and they need to flicker a lighter underneath it that erases the ink and reveals the real code.

Magic doesn’t have to be an expensive, custom-built illusion: it can be cheap and done in the hands of your guests. It’s about getting into the habit of looking at effects and thinking “how might I be able to use this to create a magical moment in my experience?”

The WXO Take-Out

The world of magic can seem impenetrable, difficult and bombastic – but Hickman proves that with a beginner’s book of tricks, some practice and a little imagination, you don’t have to be a professional magician to apply magical principles to an experience to make it more surprising, memorable and exceptional.

Even if you don’t translate specific tricks into your experiences, looking at magic design can help you understand story and structure and use misdirection and aliefs to see your experiences through a different lens.

So next time you’re designing an experience, ask yourself:

- What am I trying to get people to believe in this experience?

- What aliefs are they coming to my experience with – and how can I take advantage of those aliefs to heighten their experience within the world that I’ve made?

- What impossible things can I do that they’re going to remember and tell people about afterwards?

Want to come to live Campfires and join fellow expert experience creators from 39+ different countries as we lead the Experience Revolution forward? Find out more here.