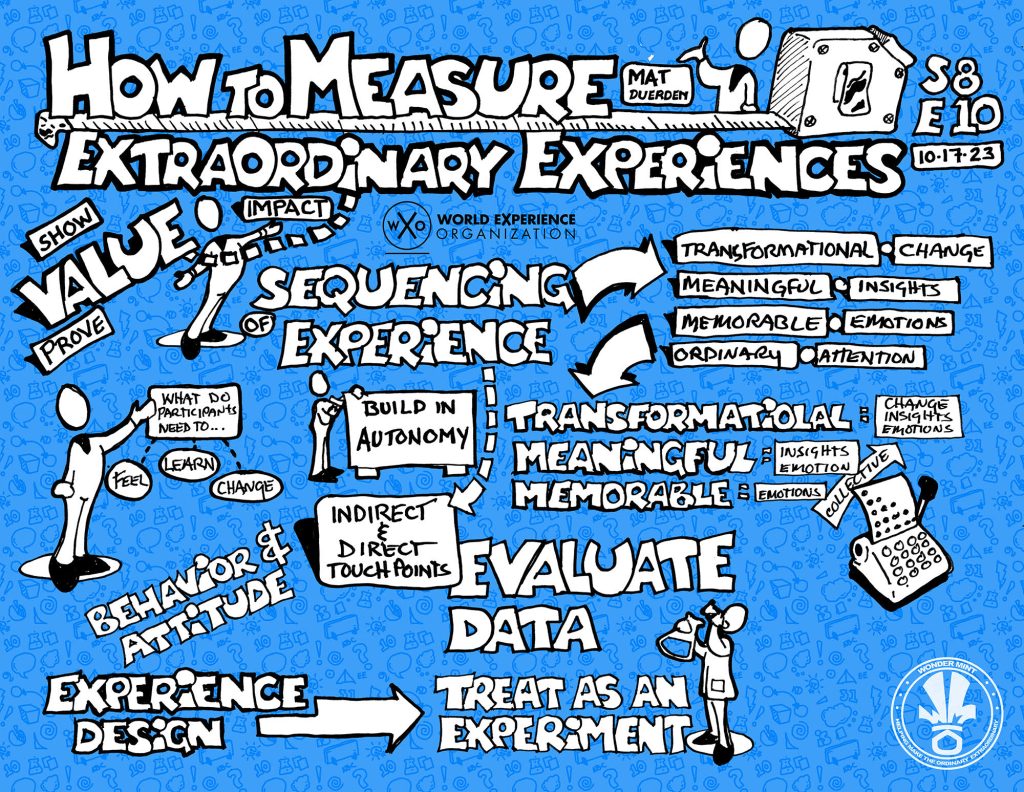

How do you measure if an experience is truly extraordinary?

Mat Duerden, Associate Professor, Department of Experience Design and Management, Brigham Young University, has been working on a project that tests how extraordinary experiences measure in the real world. It gives experience designers a good sense of how participants are perceiving their experience in terms of it being ordinary, memorable, meaningful, or transformative – and it’s only three questions long, with data to show that it correlates with NPS.

In this Campfire he gives us an exclusive insight into the process, revealing:

- How to design experiences that intentionally balance the ratio of ordinary and extraordinary touchpoints.

- How to design and sequence ordinary and extraordinary touchpoints across the anticipation, participation, and reflection phases of an experience.

- Tools to measure participants’ perceptions of ordinary and extraordinary experiences.

We believe that having a clear measurement system and/or certification for experiences is crucial to drive the Experience Economy onwards, both in terms of demonstrating the impact of our work to clients and being able to design better experiences for customers. Here’s what we learned from Duerden’s ideas.

The Impact Of Prior Knowledge On Immersive Experiences

Duerden’s family has a whitewater rafting company, so he grew up guiding multi-day wilderness trips in Idaho.

“I would see people change in terms of behaviour, and the way that relationships were formed among groups that didn’t know each other beforehand. I wanted to know: what was it about this experience that was leading these changes, so we could make it even better and grow our business?”

Mat Duerden

Later on these questions stayed with him. What is it about certain experiences that impact people? How do we break them apart to understand how they work – and then use these insights to build more and better experiences in all kinds of different contexts?

He had a chance to put some of these questions to the test in his dissertation project, where he worked with a nonprofit that provided international immersion experiences to 12 to 16-year-old children all over the world. For a trip to the rainforest and the Andes, there was a preparatory curriculum where kids would learn about topics related to deforestation and different cultures in the classroom in order to get them ready to travel. They would then travel and have these really immersive experiences.

Duerden wanted to know: what’s the unique contribution of having this indirect learning experience sitting in a classroom, and then actually being in the rainforest? He looked at this both qualitatively and quantitatively to try to understand the impact of these experiences on environmental knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour, coming away with two main learnings:

- The importance of sequencing. Going to the rainforest and talking about deforestation, ecology, and all of the topics associated with such an amazingly biodiverse space is potentially transformative. But it’s much more likely to impact attitudes and behaviour if people are primed with the right knowledge before they come. The children who scored in a threshold level were better prepared to come to the rainforest and have it impact them.

When we want to design for transformation, we need to think about how we sequence experiences. What do people need to know and be able to do, so when they come to the experience they can be most impacted? It’s really hard to change behaviour by just telling people information, but if it’s not coupled with direct experience, it doesn’t really move the dial. But we can also provide immersive, amazing experiences, and if people aren’t prepared for them, it can also not move the dial. - The role of autonomy in experiences. The children felt more connected to nature when they were in the Andes, which was a surprise in terms of ecological diversity and the topics they were focused on. Duerden thought the rainforest would be the place where they really saw movement on the measures they were collecting.

One of the things that came out in interviews is that when they were in the rainforest, they were constantly telling the kids what they could and couldn’t do to stay safe – so there were lots of parameters for how they could experience it. In the Andes, there was a little bit more freedom. From a self-determination theory, we therefore know that building autonomy in experiences is really important.

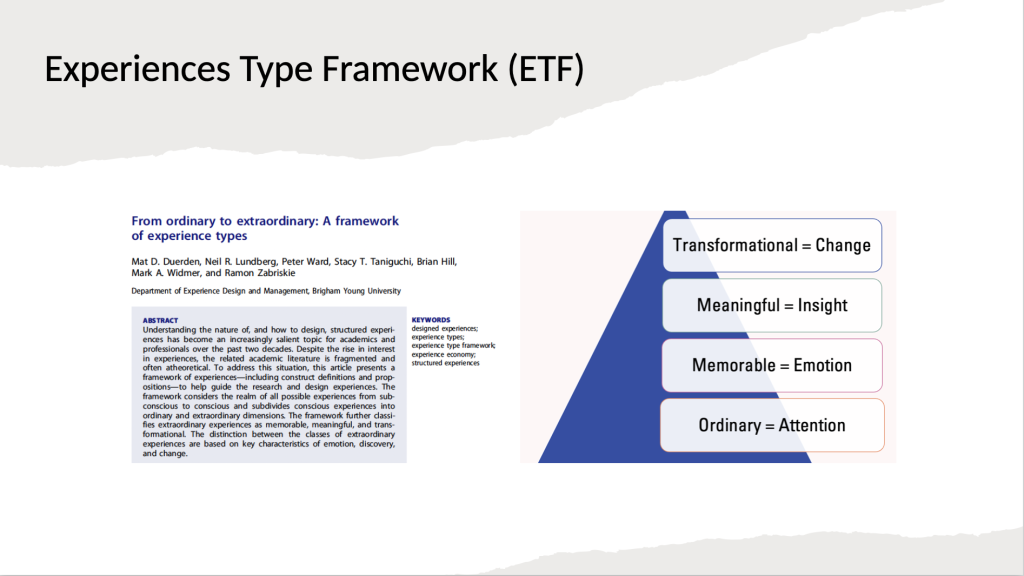

The Hierarchy Of Experiences

Around 2016, Duerden and a number of colleagues started talking about how the Experience Economy was taking off and all these experience conversations were happening. They wondered what people were actually talking about when they said you need to provide a “memorable experience”, or that every interaction with the customer needs to be meaningful, or the “transformation economy”.

They started digging into the literature to try to get a sense of the difference between an ordinary and extraordinary experience, or a memorable and meaningful one, publishing a paper – “From ordinary to extraordinary: A framework of experience types” – in 2018. Its basic proposal was that there’s a hierarchy of experiences, where each former stage must be present in order to progress to the next.

- Ordinary. For an experience to occur, you’ve got to pay attention to it. In some ways, you can think about experience design as attention design – because if nobody pays attention to it, it doesn’t happen. Most of the things we pay attention to and the experiences we have are fleeting – they don’t really make an impact. You don’t remember what you had for lunch 17 days ago, unless it was something that really stood out. But extraordinary experiences stick with us.

- Memorable. When there’s a strong emotion involved, it signals to our brain that something’s happening and to timestamp this.

- Meaningful. If you have attention, emotion and insight, your experience becomes meaningful. You learn something about yourself, the world around you, or other people, which coupled with strong emotion, becomes meaningful.

- Transformational. When you have attention, emotion, insight and change, then you’re in this transformation space. How this happens is complex – it might be in a moment or over time. It might be just an attitudinal change, or an entire identity change. But at its core, it’s about change.

The Experience Type Scale

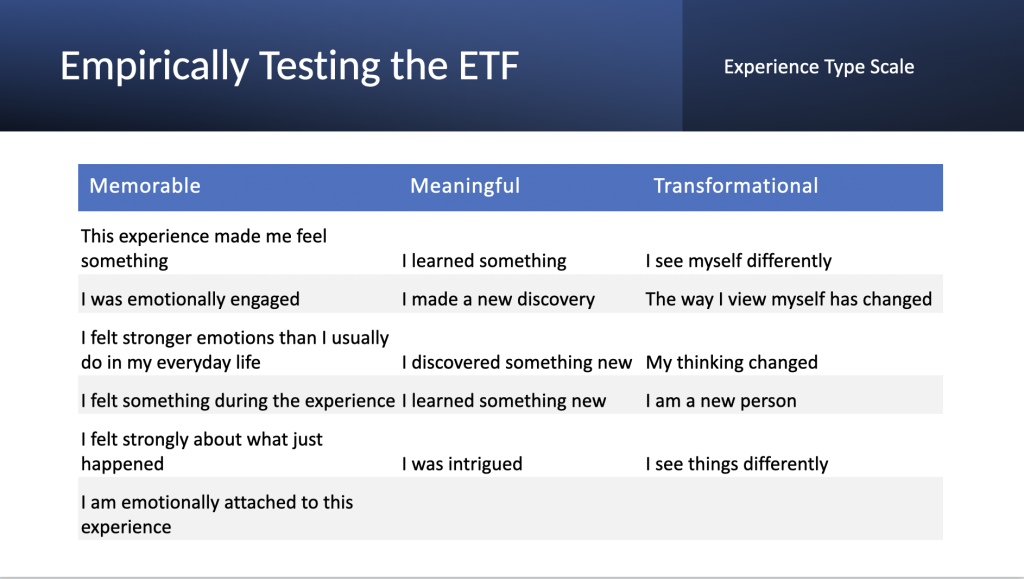

Having proposed this hierarchy of characteristics, Duerden and his colleagues wanted to empirically test it. They developed a couple of different measures including the experience type scale, where they articulated statements based upon how we define memorable, meaningful and transformational experiences.

They then started testing these statements in the real world, from real experiences to online surveys to lab experiments, trying to get a sense from people of how they perceived the experiences in terms of emotion, insight and change. This is the list of statements they gave to people:

Firstly, they learned that the framework works.

“It’s very rare for someone to say, ‘I experienced change in this particular experience’ and then say ‘but I didn’t have any insights or emotion’. It’s very unlikely in our data for someone to say, ‘I gained an insight” and not to have experienced an emotion. So the hierarchy holds up pretty well more than 90% of the time.”

Mat Duerden

They also discovered a strong correlation with NPS (Net Promoter Score). There were clear statistical differences between people just saying an experience was ordinary and that it didn’t impact them, and those that were considered memorable and meaningful had higher NPS scores. While they didn’t have longitudinal data for this particular data set, it does give a score that can be used to understand what your promoters and detractors are saying.

It allows you to have some targets to move your NPS score up – for example, to start thinking about what emotions you want to target, what insights you hope people gain, or what change you’re trying to nudge people towards.

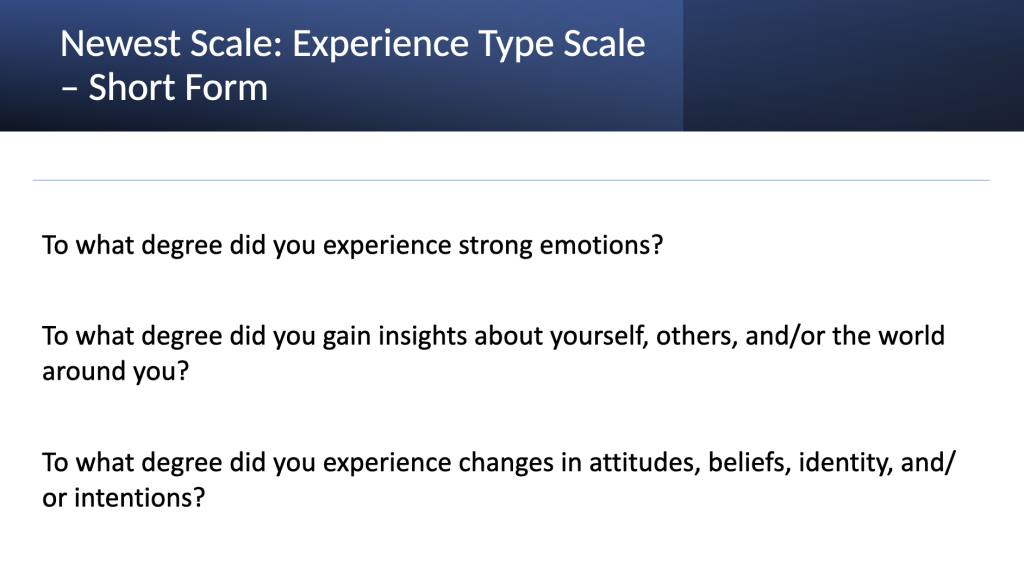

They then looked to create tools that are a little bit easier to use, with three questions rather than 15. This is what they came up with:

It performs similarly: the frameworks hold up and you can see the correlations with NPS scores. These questions also make it much easier to measure along touchpoints and not just one point. If we know that these are the key moments that we hope are memorable, we can now see if that’s how people are actually perceiving them. This allows us to look at the flow of experience. It’s also a way that we can more easily collect longitudinal data, because the cognitive ask is pretty low.

Key Considerations When Designing An Extraordinary Experience

The outcomes of these questions have nudged Duerden towards the following insights:

- Attention is a limited resource. At some point, people don’t have more attention to give. So we’ve got to be really careful, mindful and gracious towards the people that we’re designing experiences for that we design ordinary touchpoints so it’s easy to register, or login, or park, or whatever is necessary for the experience to occur. If they’re not designed well, they start sucking up attention and become negatively memorable.

- We need to think about the anticipation, participation and reflection stages. What do participants need to know? What do they need to feel? How much attention do we hope that they come with? What are we doing before the experience happens so they’re where they need to be when they arrive? Across all the phases, it makes it much more likely that they integrate that experience after they return to their ordinary world.

- Sequencing ordinary and extraordinary touchpoints. If we only have this much attention to ask for, how do we get people to spend it? We’re used to thinking about how people spend money across the course of an experience, but we could spend more time thinking about how they spend their attention. What’s the groundwork necessary to give people the knowledge and get them in the attitudinal state that you want them to be in?

Customising Your Experience To Promote Transformation

In a recent study titled “Mass Customizing Anticipation To Promote Transformation”, a team of researchers at the University of Queensland did research in museums, zoos, and aquariums to figure out how to prime people in the anticipation phase to lead to behaviour change.

Aquariums and zoos want to promote environmental behaviour or awareness of animals’ needs. But most experiences in museums and aquariums don’t lead to long-term change. So the researchers did a series of studies looking at how people’s values impact how they interpret an experience.

After looking at different value frameworks, they came up with four value profiles – this person values fiscal responsibility, this person values animals just because they deserve to be protected, etc. When people entered the aquarium or zoo, they would be presented with these four profiles and asked which one they most aligned with. Based upon that, they would be given a short info sheet that primed them for the exhibit in a way that aligned with their values. At the end of the experience, they were given a postcard with potential behaviours they could engage in that also aligned with their values, but under the umbrella of targeted behaviours that the institution wanted to see people do. Finally, they followed up and tracked if they did those behaviours.

“It’s a beautiful example of designing for transformation, and leveraging mass customization, but in a way that didn’t require doing a different experience for every single person.”

Mat Duerden

The WXO Take-Out

In Duerden’s words:

“Designing for transformation is tricky and requires intentionality. Sometimes transformation occurs serendipitously. But I think it requires intention if we want it to happen at a higher rate.”

Mat Duerden

Duerden’s research shows that it’s important to identify your emotion, insight, and change targets, and to sequence indirect and direct touchpoints intentionally. Finally, measuring and assessing through something like the experience type scale short form is crucial – there are a lot of ways to measure your process, but the most important thing is thinking of the targets you’re aiming for, and then figure out how you’re going to measure them.

So next time you’re designing an experience, ask yourself:

- What do the participants of my experience need to feel?

- What do they need to learn?

- How do I want them to change over the course of the experience?

Want to come to live Campfires and join fellow expert experience creators from 39+ different countries as we lead the Experience Revolution forward? Find out more here.