We’re firm believers that our most precious resource isn’t money – it’s time.

How we spend our hours equals how we spend our days, years and lives. In particular, the pandemic has taught us that life is finite and fragile, so we can’t take time for granted.

Yet no matter who we are, we’re all allotted just 24 hours a day, and live in a culture that keeps us feeling rushed and like we never have enough.

However, is it really more time that we need – or just the knowledge and tools to improve the quality of the time we do have?

As we learned from Rory Sutherland in Campfires 48 & 49: Who Wants To Be An Experience Alchemist, rather than changing the thing itself, changing how we perceive something is often easier, cheaper, and more impactful.

Cassie Holmes is a Professor at the Anderson School of Management at UCLA, where she teaches a wildly popular MBA class about the science of happiness and time design.

In her new book, Happier Hour, she brings together over 15 years of research to reveal empirically based insights into how we can make the most of our hours, both in our personal lives and the experiences we design for others.

We invited her to share some of her groundbreaking research and simple strategies for changing our perception of time, before applying them to how we design our own experiences.

Whether it’s turning routine into ritual, investing in commitment devices, or understanding the true value of our limited hours, we think Holmes’s work is an essential gateway into helping people make the most of their most precious resource.

Here’s what we learned – and for more tips on designing time, read our reports on:

- Campfire 73: The Transformative Power Of Time Well Designed With Alex Soojung-Kim Pang

- Campfire 51: Indistractable! With Nir Eyal

- Campfires 85 & 86: What The 4-Day Workweek Means For Experience Design With Alex Soojung-Kim Pang

- The Time Book Trend – 5 Essential Guides To Time, Life, And Experience Design

Why Happiness Is Not A Luxury

Holmes defines happiness as subjective wellbeing: both in the sense of how we feel in the moment, and how satisfied we are with our experiences, days and lives.

Historically, happiness might have been seen as something light, or a luxury. However, with anxiety and burnout rates reaching new heights in the wake of the pandemic, we now have a better understanding of why happiness is worth prioritising – and that taking care of our emotional wellbeing is neither frivolous nor selfish.

When we feel happy, it manifests in all areas of our lives.

- Work: we show up more creative, more productive, and more engaged.

- Relationships: we’re more likely to help other people and be well-liked.

- Health: happiness increases our immune and pain threshold and helps us respond better to stressors.

In short, when we’re happier in ourselves, we’re healthier, more helpful and more useful members of society: all things worth aspiring to and designing for. So how can we invest our hours to feel more satisfied with our lives?

The Time Poverty Pandemic

You’ve probably had moments in your life when the pressures on your time felt like they’d reached a breaking point.

For Holmes, this happened when she was rushing to catch a train home after a work conference to get home to her four-year-old.

“I remember vividly being sunk in my seat and feeling so depleted, wondering if I could keep up between the pressures of work and of being a good partner, mother and friend. There wasn’t enough time in the day to get everything done, let alone to do it well, and definitely not to enjoy it.”

Cassie Holmes

There’s a term for this feeling of having too much to do and not enough time to do it: time poverty.

46% of Americans report feeling time poor. It’s most acute in women, dual-career couples and the parents of young children, but touches people in all walks of life and around the globe.

And as well as being prevalent, time poverty has detrimental effects. It makes us less healthy, as we cut out exercise, eat fast food, and delay seeing our doctor. Less nice, as we don’t make the time to slow down and help others. And less confident, as we put off doing what we want to.

“On that train, the solution seemed obvious: I should quit my job and move to a sunny island. If only I had all the hours of my days to relax, surely I’d be happier? But then I wondered: are people with lots of discretionary time truly happier?”

Cassie Holmes

To answer this question, Holmes set about testing the relationship between how much discretionary time people have and how happy they feel, based on the regular days of tens of thousands of working Americans.

She found some consistent patterns. Perhaps unsurprisingly, people with too little discretionary time – less than two hours per day – were less happy. But more interestingly, those with too much time – more than five hours – were also less happy.

It turns out that having too much free time undermines our sense of purpose. Humans are averse to being idle, so when we have nothing to show for our hours we experience a lower sense of purpose and higher dissatisfaction.

The solution, therefore, isn’t to quit our work. There are also ways to spend time that aren’t working that support our happiness and purpose – volunteering or a meaningful hobby, for example.

It isn’t about being time rich, but about making the time you have rich. So how do we do this?

Why You Should Chase Golf Balls And Not Sand

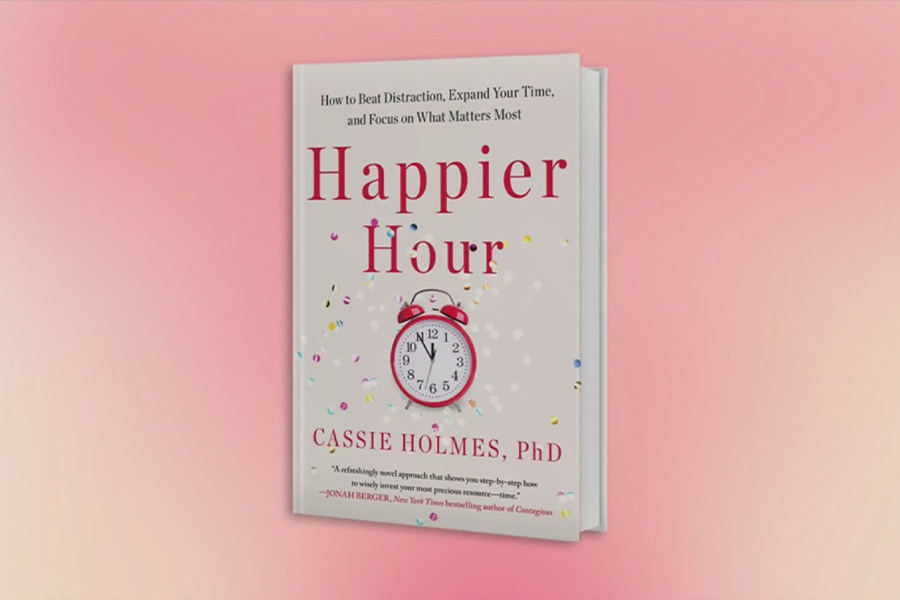

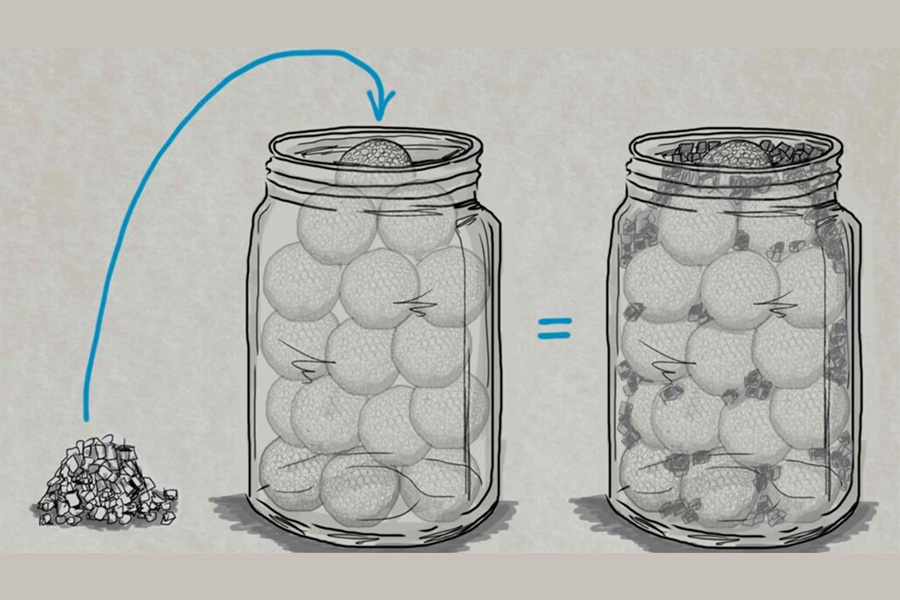

On the first day of Holmes’ course at UCLA, she shares a story with her students about “the Time Jar”.

A professor walks into a classroom, and puts a large, clear jar on the desk. He pours some golf balls in, and asks them if it’s full. When the students say yes, he adds pebbles to fill in the gaps. He asks them again – and then pours in sand. Finally, he pours a can of beer into the jar.

The jar represents all the time of your life. The golf balls are the things that really matter: family, friends, and meaningful work. The pebbles are the smaller things, like your job or your house. And the sand is everything else that will fill your time without you even realising: emails, social media, and the million other things that bombard us day to day.

The core message of the story is to prioritise. If we let the jar fill up with sand first, the golf balls won’t fit. And if we let our time get filled with the small things, it will – but we won’t have enough left to spend on the things that matter to us.

How To Protect Your Hours

In Happier Hour, Holmes sets out strategies and exercises to help people identify both their golf balls and their sand, so they can protect their hours and live happier, more meaningful lives.

Tracking our time can help us identify how much of it we spend on things that are associated with positive and negative emotions. Holmes asks her students to track everything they do over the course of a week and assign how they feel on a scale of one to 10, so they have a complete data set of what makes them feel best – and their sources of “sand”.

By looking back over this data and reflecting where you feel the most joy, you can also start to identify your “golf balls” – and how to best make time for them in your daily schedule. Holmes suggests four ways in which we might do this.

1. Transform Routine Into Ritual

One of Holmes’ moments of joy is her half-hour weekly coffee date with her daughter. This was born out of a functional routine, but reframed as a ritual. Data shows that couples that have shared rituals report greater relationship satisfaction, and families that have a ritual of gathering over the holidays are likely to enjoy them more.

This doesn’t only apply to rituals in our personal lives, but also to the experiences we create. How might we elevate the quotidian elements of our experiences into rituals instead?

“Event registration shouldn’t be a routine horrible contactless experience, but instead an incredible ritual of welcoming, gathering, breaking bread, and, oh yeah, getting your registration materials!”

Liz Lathan

Built-environment experts Zebradog recognised the power of reflection and ritual when creating a space to recognise female donors at the School of Human Ecology in Wisconsin. Rather than designing a standard plaque, they created a stained-glass window with the faces of women donors alongside a seating area, so current students could look up and not only see the past, but envisage themselves in the future.

Rather than dictating rituals for people, as experience designers our role is to create a space where they can define their own rituals. More than 90,000 people go to Disney’s Magic Kingdom each Christmas Day, with 60% of them describing it as a family ritual.

“We scripted what the ritual was, but they were still living it in their own way. If we’re really good at what we do, the experience will belong to the people who live it and not those who designed it.”

Lou Murray

But how do we keep a ritual remaining fresh and exciting, when hedonic adaptation means that as we get used to things over time, we stop noticing them?

Think of the first time your partner told you they loved you, for example – fireworks in your heart! Then compare it to them shouting “love you” as they rush out the door a couple of years down the line – less so! Something profound has become something you don’t even hear.

To protect these rituals, Holmes suggests three strategies:

- Variety helps maintain engagement and makes you pay attention. Couples who do novel experiences together report greater satisfaction and longevity – Holmes has a “Wandering Wednesday” with her husband where they do just this.

- Taking a break. Distance makes the heart grow fonder! A study of chocolate lovers asked one group to abstain for a week and another to continue as usual, reporting how much they enjoyed eating it at the beginning and end of the week. Those who had abstained reported a higher level of enjoyment.

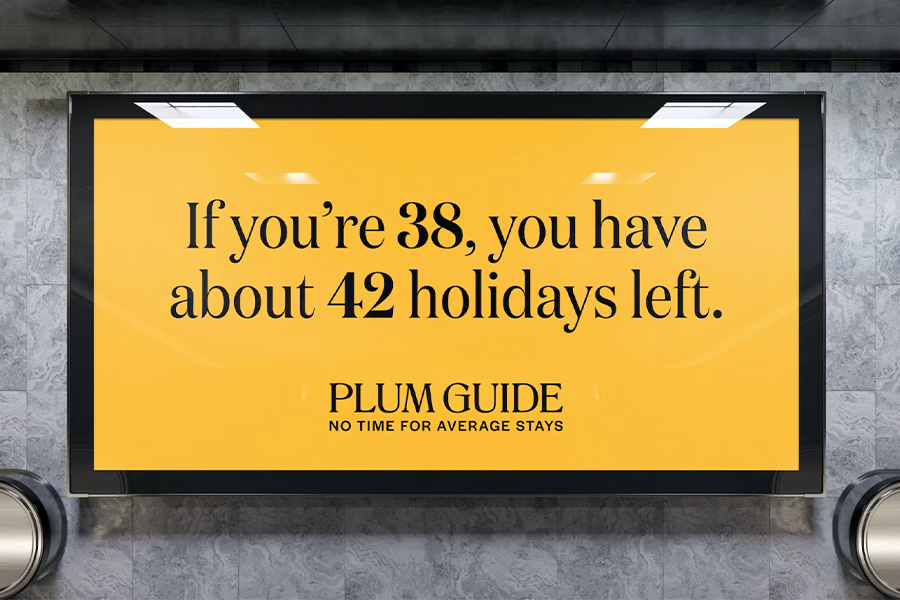

- Do the maths. Even though something may seem everyday, that’s a wrong assumption – if you identify an activity that brings you joy, calculate the number of times you’ve done it in the past, and calculate the number of times you have left and the percentage as a whole, you might be surprised by the results. These horrifying holiday ads by Airbnb-style rental company The Plum Guide are a case in point.

We may not have a lot of time, but it doesn’t require a lot of time for an activity to have a big impact. When we create a ritual, it also increases the quality of the time we spend in anticipation and reflection of it.

“It isn’t the quantity of time we have left, but the quality of time that matters.”

Cassie Holmes

Terror Management Theory suggests that a lot of what we do is about putting off the idea of death – but when we confront its reality and become aware of time passing, it can enrich the quality of our hours. And when it comes to experiences, how can we get people to realise that they won’t be doing it again, and therefore how important it is to pay attention and be in the moment?

Pigalle Tavakkoli has a fantastic example of an experience that did just this: Project Dream, created for The Wellcome Collection and an exhibition exploring death.

“We created a 1:1 experience between members of the public and a role-playing actor, where we asked the audience to think of this moment as the last five minutes of their life, and asked them what are their unfulfilled dreams or aspirations?

People cried, said they would break up with their partner, and revealed many deep and personal things. It wasn’t the length of time we spent with them, it was the quality of concentrated attention they were given and the space to be reflective and look inwards.”

Pigalle Tavakkoli

2. Create A Commitment Device

Holmes has a weekly date night with her husband. However, it’s all too easy to flake on our intentions if we don’t put safeguards in place to protect them. In this case, Holmes books a babysitter who turns up every Friday night and gets paid whether they go out or not, ensuring they commit to the date. She calls this “a commitment device”.

These commitment devices are often used for self-punishing goals like losing weight or spending less time online, but rarely for things that bring you joy, like spending time with loved ones – even though these are the really important “golf balls” that make us happy. We think this provides a real opportunity for innovation to design cool, interesting commitment devices that improve people’s experiences.

Another way to protect our designated time for the things that matter is to make them a no-phone zone. Research shows that for 47% of the time, people are not thinking about what they’re doing, and that we’re less happy when our mind is wandering.

Our phones are a major source of this distraction, even if we’re not actually using them and they’re just within sight. So put it away! (For more on how to resist the siren call of distracting technology, read Campfire 51: Indistractable! With Nir Eyal.)

3. Get Outside And Offline

Research shows that exercise is a significant mood booster. It reduces our anxiety, increases our sense of efficacy, and lessens our sense of time poverty.

A study of people’s days involving geolocation data showed that simply being outside has a positive effect on our happiness. Yet exercise is often the first thing to do when we feel like our time is being stretched.

By carving out space for a morning run or afternoon walk, we might feel like we’re wasting time – but we’re actually expanding our sense of time well spent.

4. Invest Time In Purposeful Work

When it comes to work, it’s incredibly easy to fill our time with sand: responding to emails, saying yes to meetings, and getting lost in a vortex of administrative tasks.

We might feel like we’re being incredibly productive when we do this, but we end up ignoring the work that really matters to us – what Nir Eyal calls the opposition of “reactive” and “reflective” work.

Instead, if we make sure we have uninterrupted time for purposeful work – whether this be writing, coming up with creative ideas, or otherwise moving towards our bigger goals – we’re more likely to become immersed in what we’re doing, enter a state of flow, and lose all sense of time. And it’s when we’re in this state that we’re at our most creative and productive.

“We often don’t give ourselves the space to think, as we let our time get infiltrated by other things. But making time for uninterrupted work isn’t about putting a boundary around our creativity, but protecting it. The purpose isn’t to contain, but to protect your time to think.”

Cassie Holmes

The WXO Take-Out

The more we explore the art of time well designed, the more connections we notice between the research into the topic and a life well lived.

The optimal 2-5 hours per day of discretionary time identified by Holmes, for example, seems to correlate with the 6-hour workday put forward by Alex Soojung-Kim Pang.

And the need to distinguish between reactive and reflective work and protect our time from distracting, addictive technology supports what we’ve learned from Nir Eyal’s work on creating and managing habit-forming products.

The importance of ritual also makes us think of religion and what we can learn from it.

“This is what works for humans. Experientialism is bringing back shape to a shapeless world.”

James Wallman

So next time you’re creating an experience, ask yourself:

- How might you turn the routine elements of your experience into a ritual?

- How can you convince people that your experience is worthy of their time and attention?

- How can you pack a big impact into a short timeframe?

To continue the conversation, WXO Members can head to the topic on My WXO here.

To see the full line-up for the WXO Campfires Season 5, click here.

To apply to join the WXO and attend future Campfires, click here.