This is the way the world ends, not with a bang but a whimper…

T. S. Eliot might have known his onions when it came to poetry, but when it comes to the end of the world, we’re putting our faith in experience design.

And at the forefront of the push to design better endings that contain much more bang than whimper, there’s Joe Macleod: UX designer, author of Ends (2017) and Endineering (2021), and the founder of the world’s first consumer-ending business.

Here at The WXO, we’re big fans of what Macleod does. As well as being one of our co-founders, he’s written for us about The 8 Types of Endings, why the end of the world needs designing, and was one of the Firestarters at our very first Campfire, Campfire 1: We Began With Endineering.

We also agree with him that most people on the planet don’t spend enough time thinking about endings – particularly in the world of product design and product experiences. So we’re thrilled to be welcoming him back to lead Campfires 33 & 34 with two dedicated, exclusive workshops on The Ultimate Guide To Endineering.

Why do we need to pay more attention to endings? Because, quite simply, they matter.

- Although the Peak-End Rule might be up for review – see Campfire 25: Beyond The Peak-End Rule with Wim Strijbosch – the fact that people remember the end of an experience remains a valuable tool for measuring its effectiveness.

- As psychologists Fredrickson and Kahneman discovered more than 30 years ago, the difference between the “experiencing self” and the “remembering self” means that experiences are subject to “the recency effect”. People remember what happened just now, not last week.

- As CX expert Colin Shaw said in Campfire 7: Is It Possible To Design For Transformation, “The biggest thing I’ve learned is that we don’t choose between experiences; we choose between the memory of those experiences.” So if we care about repeat business, we need to care about endings.

- There’s also a huge environmental problem with the consumer lifecycle and the way we remove things from the earth, make them into things, and then put them back in the ground. So if we care about our planet, we need to think about endineering.

So how can we endineer our way to a brighter, more bang-filled future? Over to Macleod to explain.

The Neglected Last Third

Macleod explained that there are three stages to the consumer lifecycle.

- Onboarding: think of the incredible work that many industries do to create emotional engagement, e.g. marketing, advertising, selling dreams.

- Usage: making incredible products that people can use.

- Offboarding: often overlooked as an emotional experience, endings happen briefly and without any reflection – or they go on forever, like the rubbish we accumulate in the back of our cupboards, or the services that seem impossible to leave.

So the first two-thirds of an experience are awesome, well designed, and emotionally engaging: and the last third is a lame fizzle.

“That last quadrant is tolerated by the consumer. They’re uninstructed, they’re abandoned. They’re blamed for a lot, and it’s because no-one really designs in this area.”

Joe Macleod, UX designer

If you want a real-world example, think of a printer. When your cartridge runs out of ink and you replace it, you might wonder what to do with it. When Macleod had this experience, he ended up finding out that the printing company had a great, decades-old recycling program, but he was only able to discover this by “scrambling around online”.

“It’s not connected to the consumer experience. It’s this separate thing that takes five days to complete, and it was disconnected, and I had to do it myself. The ending was hidden. And this is going on all over the place.”

Joe Macleod, UX designer

Bad Endings Aren’t Business: They’re History

We might assume that this failure is the result of hard-nosed business logic, but actually it’s something that has been created sociologically over time.

In pre-industrial times, the consumer lifecycle was visible, circular, and actionable. The waste from the kitchen table would go to the animals, the waste from the animals would go into the land, and the harvest from the land would come back onto the kitchen table.

The Industrial Revolution changed all this into a linear narrative that still exists today. We’ve accelerated consumption and usage and created emotional experiences around them so that they’ve become profound, engaging and really exciting. But the offboarding – the end, our relationship with waste – has become distant.

“It’s become foggy, it’s become scientific, and we’ve split the consumer lifecycle into a consumer self and a civil self. These individuals never meet, because we haven’t designed an experience that brings them together.”

Joe Macleod, UX designer

The Tyranny Of Terror Management Theory

The fact is, humans don’t like endings very much. We’re actually terrified of them.

Macleod cited Ernest Becker in The Denial of Death:

“Most human action is taken to ignore or avoid the inevitability of death.”

Ernest Becker, The Denial of Death

Becker called this “terror management theory”. (Ironically, he died before he completed the book.) The theory states that all of us are trying to create something which will outlive us: big, emotional life projects.

This was tested by Kasser and Sheldon in 2000, who wanted to know if we tried to buy our way out of terror management theory through consumption. They split a group of people in two and asked one to listen to jazz, and the other to think about their own mortality. They then asked all of them about their consumer habits and spending power in the future. The people who were thinking about their own death were considerably more aggressive. From this, they believed that even in consumerism, we’re trying to cheat death.

Mind The End Gap

When we treat endings like this, we create an “end gap” that causes four problem characteristics.

- The relationship breaks between consumer and provider, and that relationship is the thing that we loved and held so dearly. When this happens, it also breaks the joint responsibility to the assets, which then fall to the feet of society.

- The asset definition is lost. When I buy something I research it, I know all its definitions in terms of what it’s made of and its functions. But once I send that to waste, or remove myself from that service relationship, that definition is instantly removed. So what was a very defined thing is now another component in a massive waste stream where no one really knows what’s going on. This also happens in data, when we create big data lakes because we don’t know what to do with it. This creates a mass of unknown elements and reduces the ability to measure impact for the consumer.

- Actors and actions are anonymised. When I buy something, I own that thing. I have laws around that ownership and many layers of identity that are connected to purchase. But when I throw something in the bin, I immediately relinquish that relationship between my identity and that object. It then becomes the ownership and the problem of society and sadly, the environment. This also happens in data relationships, where I assume I have been removed from the relationship, but my identity is reestablished in the background and then I’m plied with marketing despite thinking I’ve left that relationship.

- Routes to neutralising are blurred. If I have an apple, I understand that after I finish that apple, it will decay naturally in the environment. But if I have a human-made product, for example a plastic bag, I have loads of questions about how that gets neutralised in the environment. A plastic bag is a really simple material, so there shouldn’t be many questions about it. We’ve talked about plastic bags for so long, and yet we haven’t gone one dimension up in material components to for example, a pen, which has many different components, but we don’t concern ourselves with how we’re going to dismantle that.

The 8 Types Of Ending

There are eight types of endings the customer experiences at the end of the consumer lifecycle which go across services, digital and product sectors.

- Time-out. This is when an item has a scheduled ending. This could be a degree course, the end of a holiday, or it could be the sell-by date for your lunchtime sandwich.

- Credit-out. This is when an item or service possesses a finite reserve of something, which gets used up by the consumer. Examples include batteries, or the balance of pay as you go phone credit.

- Task or event completion. This applies to the fulfilment of tasks, such as when you send a parcel.

- Broken/withdrawal. This applies both to physical products which can no longer operate beyond breakages (a vase or lamp, for example), or in situations where service providers go bust.

- Lingering. This is when the relationship with the product or service becomes ambient rather than active. It’s still there, but it’s not prominent in the life of the user. Examples include those clothes at the back of your cupboard which you never wear, or subscription services you’d forgotten about (or forgotten to unsubscribe from after an initial trial period).

- Cultural. This is the cycle of trends and shifting cultural perceptions that put an end to one type of groupthink over time. An excellent example is people’s shifting sensitivities to various forms of prejudice over the past century. On a smaller scale, the culture or politics of a brand might affect how a consumer sees it. A brand which has practices or stated beliefs in conflict with those of a prospective user might put people off. Alternatively, it might push existing users to terminate that relationship in favour of a better-aligned competitor.

- Competition. Of course, this is the big one, when you leave one for another. When you split up with someone and started seeing their more attractive friend instead, when you ditched your Nokia for an iPhone, or when you move from lager to craft beer.

- Proximity. This has to do with catchment areas. Are you inside or outside the distribution area for a service? If you move out of it, you can no longer access that service. Examples include delivery of take-out food, a local bus network, or mobile network coverage. It can also happen without the consumer actually moving location, but moving from one service provider to another. Move from Apple to Android, for instance, and you can no longer access iCloud.

The Never-Ending Story Of Work

We’re in the middle of the Great Resignation – and when it comes to endings, the lack of well-designed ones within the workspace might be a clue as to why for so many people, work isn’t working.

“There is no real ending in a job, so we end up making up endings that circle around things like our two-week vacation, or the day or two we get off around Christmas. Even in the US military, their whole resilience program is built around when your tour of duty ends and works backwards from that. I think this points to the fact that the culture of our workspaces is fundamentally broken, because there is no good ending in sight that we can gear ourselves toward. Even when we’re thinking about work projects, the mantra of ‘fail, fail, fail, fail big, fail fast’: human beings are not wired for that. There’s a grief process that has to be gone through. And if it’s not, it builds up chronic inflammation in the body, which leads to all kinds of things.”

Theo Edmonds, experience strategist

Perhaps the same could also be said for fans.

“In popular culture, they don’t want to let their stories end. The Marvel Universe is a really good example of this – they just can’t seem to let it go!”

James Wallman, CEO, The WXO

What Makes A Good Ending?

Talking about narrative endings and the importance of endings in stories, Macleod argued that what makes a good ending is a sense of moral closure – something that is lacking from many product experiences.

“Closure in narratives attempts to preserve the moral and social order which would be threatened by endlessly erring narratives.”

Elizabeth MacArthur, Extravagant Narratives

This is the opposite of what happens in consumer endings, when we instead experience a loss of asset definition, a loss of ownership, a loss of relationships and a loss of understanding. We can’t tell what the end of carbon will mean, for example – producing a lack of moral authority and closure that is shocking.

“Solid closure in conventional narratives and histories satisfies individual and social desire for moral authority, a purposeful interpretation of life, and genuine stability.”

Richard Neupert, The End, Narration and Closure in Film

As we’ve seen in our previous storytelling Campfires – see Campfires 31 & 32: Who’s The Hero – we also find endings and closure deeply satisfying, especially if they’re happy ones.

The 7 Phases Of Ending

Macleod finished by outlining the phases of ending that a consumer should go through, inspired by the “crack of doubt” theory.

This was coined by a woman called Helen Rose Ebaugh, who used to be a nun and later became a psychologist. The enormous leap in career inspired her to look into how people leave a role.

“You experience this in your early romantic relationships: you become romantic with someone, they do something, and you start to feel a crack of doubt in your mind about whether you’re well suited. The crack would have opened up until you either leave, or mend it and carry on the relationship.”

Joe Macleod, UX designer

Wallman pointed out that this “crack of doubt” could also be called a “sliver of light”, because change is borne not only out of desperation, but of inspiration.

“The crack of doubt sometimes feels not quite as positive as it could be, because it could also be a sliver of light. It’s something on the other side.”

James Wallman, CEO, The WXO

The crack of doubt is the first of 7 phases of endings.

- Crack of doubt: The first moment a consumer believes that the service or product is not fulfilling their needs.

- Acknowledged: Both parties acknowledge the consumer wants to leave. The path to the end gets momentum. The end is verbalised.

- Actioned: The consumer has an opportunity to action the end.

- Observed: Visible/tangible evidence that the end is now.

- Settled: Confirmation that all is done. It should resolve the financial debt, the obligations and the material exchange. It might not resolve all the emotional baggage.

- Aftermath: Reflecting on what’s just passed. High emotions: good or bad, angry or happy.

- Rebirth: Freedom to live again. Emotions fade with memory. Reborn, clear thinking and ready to re-engage.

The Crack Of Doubt = A Sliver Of Opportunity?

How can we transform the negative emotion of doubt into an opportunity to create repeat customers? This is a question Julian Rad was pondering with regards to a mixed-reality experience he’s working on.

“We’re building an interface that people will encounter in a way that inspires return visits. We want them to feel great engagement with the experience, not unlike the way you’ll fall into a Roblox hole or become a Fortnite fan. And so, thinking of this crack of doubt, this moment that is not fulfilling their needs: how does the consumer feel that it’s not? How do you take a new technology and a new way of experiencing a digital world and redefine that need?”

Julian Rad, creative director

Perhaps the crack of doubt is all bound up in our identity, and therefore presents an opportunity for experience creators to allow us to be “born again”, or transformed, with a different identity.

“When I think about the different products, services or even jobs where I feel the crack of doubt, one of the key questions for me is: is this me? Who was your customer before they came to your experience, and what have they had to sacrifice to attend it? They need to have felt that crack of doubt in order to try your thing in the first place.

I think there’s a lot of opportunity here. If you give them that sense that when they come out they’ll be ready to live again, then maybe they’re going to want to come back around that circle again with you.So you can use this thinking of the phases of the ending as examples of how there are opportunities in where people are coming from, as well as how they leave your experience.”

James Wallman, CEO, The WXO

As Rad responded, the ending is an opportunity to upsell.

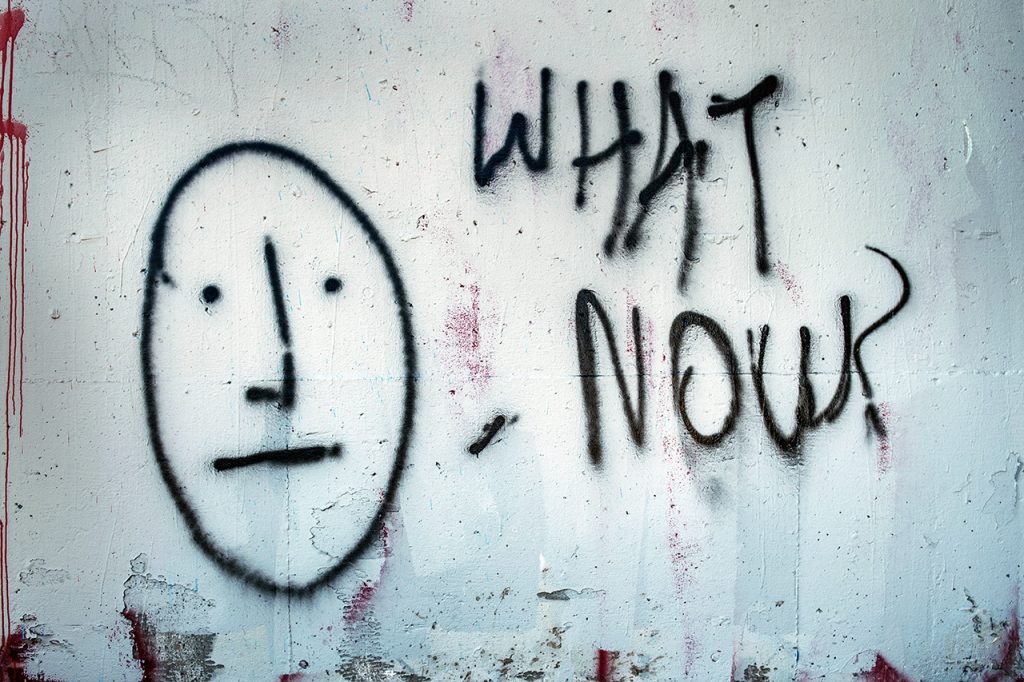

“Maybe what you’re creating is the first step in building a community. The thing that everybody craves is: what’s next?”

Julian Rad, creative director

Fighting Boredom: Endings That Never Come

Perhaps the crack of doubt could also signpost moments of weakness in an experience – like boredom – and highlight opportunities to build more satisfying endings that in turn, are more likely to lead to repeat visits.

Sophie Shaw saw the potential for applying this mindset when it came to museums and exhibitions. We’ve all experienced a museum visit that went on a bit too long, leaving us with nothing more lingering than sore feet.

“What would be the ideal moment where the visitor thinks, ‘I might be nearly done here?’ Is it an aha moment? Is it a few moments after an aha moment? And then how can we provide an exit so they don’t have to go through more stuff they don’t want to see?”

Sophie Shaw

Architecting possible exit moments might feel counterintuitive, especially in a world where we’re used to thinking about time spent on device, and using apps designed to keep us interacting for as long as possible so they can make more money from us. However, if we go back to Colin Shaw’s point about people remembering the memory of experiences above the experiences themselves, maybe boring people out of our experiences is the bigger risk.

“The ending is so important in terms of what they remember. So if their memories of the British Museum are that it was awful and boring at the end, it’s better to design something shorter and punchier.”

James Wallman, CEO, The WXO

When it comes to endings, outstaying your welcome can also be more damaging than desirable. Lighting designer Koert Vermeulen had an interesting example of exactly what happens when you don’t have a clear “acknowledgement” of an ending.

“When you hear the applause or see the standing ovation, you get the acknowledgement that something is finished. But there’s a show that’s been running for 10 years in Puy du Fou theme park in France that uses a double finale. I always feel so bad for the audience, because they’ve been sitting outdoors for 96 minutes, sometimes in the rain or the cold. So when the finale comes, they start clapping and standing up.

But then the second finale begins. People awkwardly sit down again or stand clapping for five minutes. If you do a double ending, you’re competing with your own product and making people feel awkward. That’s just rude!”

Koert Vermeulen, lighting designer

Fighting FOMO: Designing Infinite Endings

But what if your experience doesn’t have a distinct end – think immersive art experiences, Disney theme parks, or some kinds of modern games? If you’re building an infinite, open world, how can you design mini-endings to prevent overwhelm, but still leave room to explore and return?

“How do you present someone with so much saturation that there is no way that they will experience everything, but still give them an exit point so that they’re not leaving exhausted? How do you present an ending when the goal is infinite possibility?”

Claire Chapelli, immersive producer

Kevin Dulle had a potential solution that reminded us of Bob Rossman’s idea of a “memory anchor”, way back in Campfire 1.

“We have a wonderful zoo in St. Louis. There’s so many things going on, so in each section they used to give you what they called the zoo map token. As you would go through they would punch when you completed a tour. If you came back to finish it, you got a discount. So is there a reminder or token they can take with them to bring them back?”

Kevin Dulle, visual thinkologist

In addition to providing different exit points, could we also create different entry points? This is something that the world of gaming does particularly well, with levels and rebirths.

“When your character dies in Roblox, you go back to a particular spot. So just as we think about exit points, is there a different entry point we could use? In terms of product endings, too, rather than the anonymous nature of throwing out your trash, could there be a more satisfying way of recycling that makes you feel like you’re going up in the world or becoming a better person?”

James Wallman, CEO, The WXO

The WXO Take-Out

As we hurtle towards the end of the world, designing “good” endings to experiences has never been more important. So experience designers can ask themselves:

- What does the end gap look like for my product or experience?

- What kind of ending do people have when they exit my experience?

- How could I provide my audience with a satisfying sense of closure?

- When might my audience start to experience a crack of doubt – or a sliver of light?

- Or, what might have already caused them to experience this BEFORE they come to me?

- Am I boring my audience or making them feel overwhelmed? How could I better design an ending – or endings – to counter these feelings?

With that in mind, we’ll make what Macleod called “an airport exit”:

“It’s the emotional point where you think, I feel settled. I love the airport when you come into the arrivals hall and you feel like the journey is done. Those are the most amazing places. You see people laughing and crying. It’s the cathedral of emotion.”

Joe Macleod, UX designer

You can buy your copy of Endineering on Amazon now.

Interested in taking part in discussions about experiences and the Experience Economy? Apply to become a member of the WXO here – to come to Campfires, become a better experience designer, and be listed in the WXO Black Book.