Who makes for the better hero: Spider-Man, or the entire Marvel Cinematic Universe?

We’re not sure we have the answer (yet)… but two people who might are Dr Moniek Hover, a Professor of Storytelling who teaches leisure, tourism and imagineering at the Breda University of Applied Sciences, and her colleague Dr Licia Calvi, a fellow lecturer and researcher in how to apply storytelling.

Together, the pair have worked on several projects that use storytelling to bridge the gap between humanity, heritage and nature, as well as bring tourist destinations to life. And while their work might focus specifically on placemaking, we think the questions it brings up are relevant to experience designers across all sectors.

- What’s the difference between telling stories that are focused on a solo hero and those that are built around a team of heroes?

- What types of stories are best at connecting with audiences?

- How should they be applied differently?

- And most importantly, what’s the proper way to pronounce “Vincent Van Gogh”?

We invited Hover and Calvi to share some of their learnings from their Becoming Vincent and Crossroads: 40-45 projects with our Campfire in a double session, and the latest of our storytelling-specific Campfires (catch up on Campfires 27-29 here). Here’s what we learned.

Narratives Are Informational, Stories Are Emotional

Having schooled us on the different pronunciations of Van Gogh in the north and south of the Netherlands, Hover made an important distinction between narratives and stories.

“A narrative is a more factual account that aims to provide information to people – facts and figures. A story is an account that aims to touch people emotionally and thus give them an experience.”

Dr Moniek Hover

She pointed out the difference between talking about the military Operation Market Garden of 1944 in terms of the number of airplanes involved or people killed, versus through the lens of a young couple who suffered a tragic loss that remained unresolved for decades. One gives us the facts; the other gives us the story.

We Need Empathy, Not Heroes

Do we need another hero? If Calvi (and Tina Turner) are anything to go by, maybe not…

All stories need a protagonist. But the protagonists we’re used to from Greek mythology are superhumans who undertake gargantuan feats. They might be impressive, but they’re not relatable.

To connect with ordinary people, heroes need to be one thing: empathetic. (There’s an obvious link here to social anthropologist Manvir Singh’s work on the universal “sympathetic plot” that appeals to human nature, as explored in Campfire 29: The Universal Ingredients Of Story.)

“Empathy is the most crucial element in a story, because empathy is what allows people to feel narrative transportation: to be drawn into the story, forget about what’s around you, get into a flow state and become part of the story itself.”

Dr Licia Calvi

Empathy goes deeper that identifying with someone or feeling sympathy for them: it means being able to put ourselves in their shoes.

The Empathetic Plot Design

So what does empathy mean for design? How can we use it to create better experiences?

Hover and Calvi have formed a framework for placemaking that uses story and empathy as anchors. It looks something like this:

Story –> Empathy –> Emotional experience –> Visitor connection to place

By looking at the universal values behind stories, we uncover themes that resonate with everyone regardless of cultural background or personal experience, generating empathy. This empathy helps form an emotional experience. And this emotional experience translates into a connection between the person visiting a place and the story behind it.

In other words, context is everything: what people know before visiting a space, and how you introduce them into that environment, is crucial in forming their attachment to it.

A Portrait Of The Artist As A Young Man

Hover and Calvi were approached by the Dutch province of Brabant in 2014, which wanted to use the story of Vincent Van Gogh – who spent most of his life there – to rebrand the region and draw attention to its other attractions.

Using their empathetic framework, Hover and Calvi came up with Becoming Vincent: a storytelling project that enabled visitors to Brabant to both visit the places where Van Gogh had lived as a young man and became an artist, and also “become” Vincent by discovering elements of his story to which they could relate.

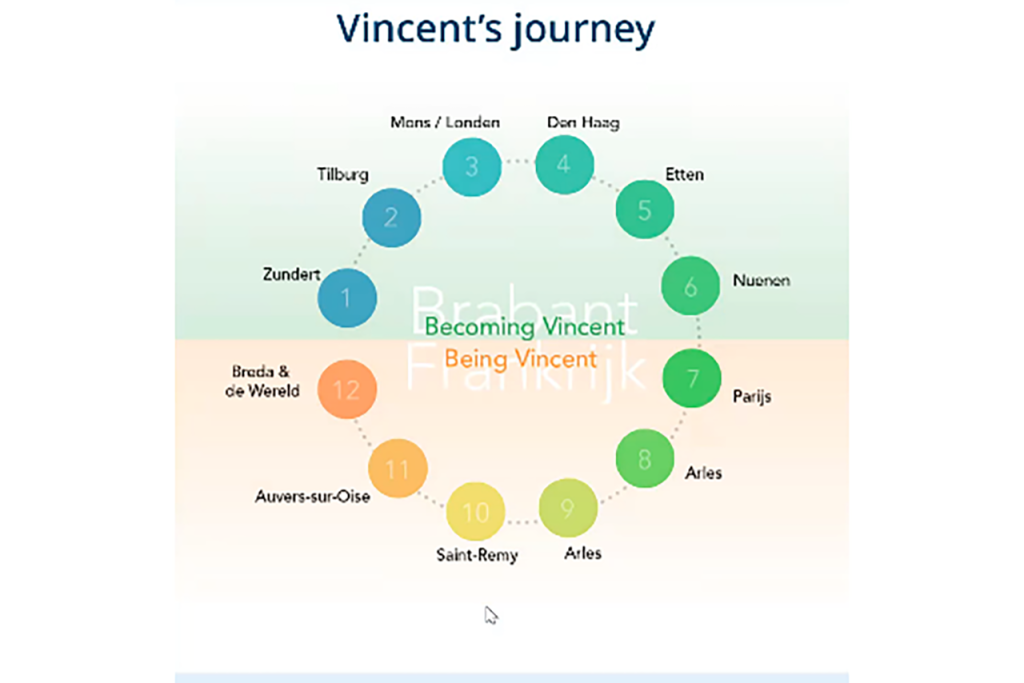

To do this, they used the classic 12-step Hero’s Journey model, mapping each turning point in Van Gogh’s life to different cities in the Brabant region. When visitors follow Van Gogh’s Hero’s Journey, they also go on a journey through Brabant.

The Problem With Empathy

During their research, Hover and Calvi found that international visitors associated certain facts with Van Gogh: his famous Sunflowers, the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, cutting off his earlobe, or living in Provence towards the end of his life. Rather than looking at these facts, they chose to focus on his deep connection to his younger brother as a story hook that people could relate to, feeding this story into the design of the information center.

However, people are complicated, and empathy has its limits. Hover recounted an episode in Van Gogh’s life where he stalked a girl who had rejected his advances, causing arguments with both the girl’s and his own father. Where people could empathise with other struggles in Van Gogh’s life, they found this sort of behaviour harder to stomach.

Their solution was to select the elements of the story that people could more easily relate to and find another hero – in this case, Van Gogh’s brother, who supported him practically and emotionally. When it came to the stalking anecdote, they focused on the fights with his father, which many respondents could remember and recognise in their own lives. The key was to carefully select the elements that would resonate most.

Using Small Stories To Communicate Big Themes

Following the success of Becoming Vincent, the Brabant province asked Hover and Calvi if they could do something similar to tell the story of the Second World War in the region, highlighting significant heritage sites such as a former concentration camp and the biggest war museum in the Netherlands.

Brabant had witnessed many of the big themes of WW2: occupation, persecution, resistance, and liberation. To find one person to represent all of these experiences would be impossible. Instead, Hover and Calvi decided to sift through the thousands of stories of people connected to those themes to find those that would most resonate with people, coming up with Crossroads: Life-Changing Stories 40-45.

“Crossroad stories are about people’s turning points, encounters, choices and dilemmas. We didn’t want to tell the full historical narrative, but instead focus on this one child or this one soldier and tell their story in a way that touches people’s emotions and gives them an enriching experience. And hopefully, results in a change in attitude towards becoming more tolerant.”

Dr Moniek Hover

They hosted 15 events across the province to collect stories not only from historians, but also from personal testimonials, resulting in 800 potential stories and 75 final stories – one for each of the years since liberation.

The Magic Of The Window Story

The challenge with choosing 75 stories from thousands of potentials is that you inevitably prioritise some above others – plus, those you do select have to somehow represent the rest. Particularly when dealing with sensitive subject matter such as war stories, this can present a dilemma.

Hover and Calvi got around this problem with what they call the “window story”.

“What I like about an Italian shopping street is that the shop windows aren’t crammed. They have one pair of beautiful boots that draw your attention, and when you’re so touched by it that you go into the shop, you see that they also sell belts and jackets and shoes. That’s what we wanted to do. We want this one story in a window that people will be touched by and will draw their attention. Then they go into the museum or the visitor center or the internet and find that there’s so much more.”

Dr Moniek Hover

Hope = Happy Endings

We’ve established in previous Campfires (see Campfire 29 in particular) that for the most part, people prefer happy endings. We read love stories or fairy tales because they make us feel good. So when faced with war stories that may not end happily, how do we tell them in a way that still draws people in and tells the truth of that person’s life?

For Hover and Calvi, the magic ingredient is hope.

“We looked at Greek drama and saw that even though it often ends badly, you still learn something about human values and choices that enriches you as a human being.”

Dr Moniek Hover

Who’s The Hero (Again)?

The topic of who the hero should be – brand or customer, single hero or collective – has cropped up repeatedly in our Campfires, most notably in Campfires 27-29. When selecting a hero to represent the stories of many who had suffered, finding an element of hope was an important aspect of choosing the right window story. The story of a concentration camp child survivor who went on to become a psychologist who works with traumatised people worked well as it turned hardship into something beautiful, for example.

However, some stories are more complex. Hover mentioned the story of a young German soldier who was killed under fire when trying to help return some Dutch children safely to their mother. While the family wanted to celebrate his heroism, the villagers under occupation did not.

There is no easy answer as to who the heroes in a story should be. Perhaps everybody can be a hero, depending on who tells the story and how.

“All the people that have been mentioned are literally heroes, but they are also metaphorically heroes because they went through difficulties. They had to face struggles and turning points in their lives. And they all express some universal values in which each of us can recognise ourselves. Because of this, we feel for them. Through empathy, we are attached emotionally. And we have a more enriching and transformational experience.”

Dr Licia Calvi

Life Is Stranger Than Fiction

When it comes to fiction, there’s a rule – popularised by Pixar – that your hero can get into trouble through coincidence, but they can’t get out of trouble by coincidence, as this makes for an unsatisfying story. Think of the entrepreneur or start-up myth: we love to hear about the hard work that got someone somewhere, but less about the luck.

However, life doesn’t follow the same rules – Hover and Calvi saw several examples of this in their research. So we have to be careful with how we handle these stories, or select stories that give a sense of agency to their protagonist.

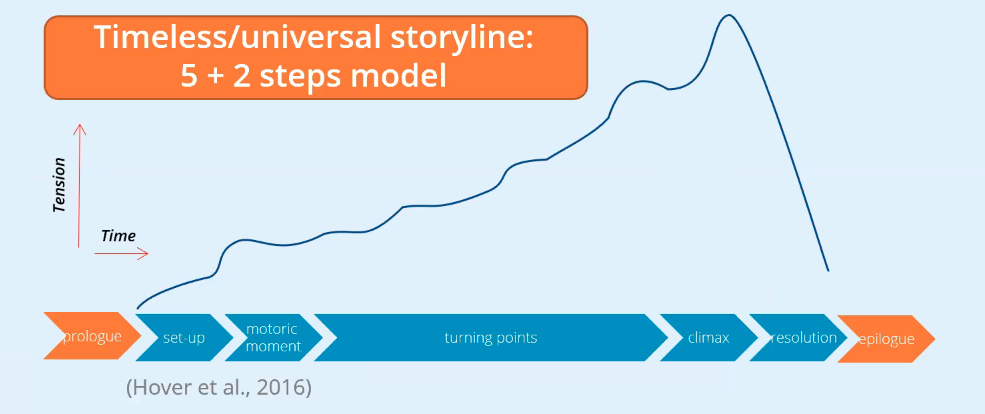

The Five-Step Storytelling Format

For the Crossroads project, Hover and Calvi wanted to find a format that they could give to historians or journalists to write them up.

“If you leave it up to a historian, they will come up with a 20-page story. A journalist will come up with a linear narrative that gives away the key events too quickly.”

Dr Moniek Hover

The 12-step Hero’s Journey format they used for Becoming Vincent was too complicated in this instance, so they used a five-step format:

This format is particularly effective when the NPS score of an experience is very high, but the repeatability is low – visiting a concentration camp, for example. This is because it focuses on giving people a story to share with others to inspire them to try the experience themselves.

Transmedia Storytelling Offers Different Ways In

Once they had the 75 stories for the Crossroads project, Hover and Calvi helped to design different ways to tell them, including:

- 75 AR mini-documentaries unlocked in different places via smartphone

- A maze where you hear parts of the stories as you move through

- Art sculptures representing a key turning point from each of the 75 stories

The greater number of ways to represent a story, the greater chance there is for different people to connect with it or for it to resonate in different ways.

Choose Your Own Adventure

With Hover and Calvi having concluded their presentation, Douglas Steel wondered if the concept of the “window story” or single storyline could be quite limiting. Wouldn’t it be better to give visitors the chance to choose their own adventure – both for the quality of their experience, and the bottom line?

“Why are you making the choice to develop a single storyline? Within a museum with multiple touchpoints, the narrative that connects those encounters can vary. You could create a storyline based on the experience of an eight year old girl, or a 60 year old man, or an obsessive compulsive person. You don’t have to decide what the best story is. And wouldn’t it drive increased revenue if people go back to the same installation, but opt into a different storyline every time they go so they don’t have the same experience?”

Douglas Steel

However, the beauty of the window story is that it isn’t an end point – it’s a gateway.

“You have this one window story, but the minute you go into the museum, you see there’s many stories. In the War Museum in Overlund, they have many different personal stories from Queen Wilhelmina to the head of the SS in The Netherlands to a mother and child.”

Dr Moniek Hover

We might also call it an umbrella story, within which we can each choose what resonates most for us. But it’s perhaps worth pointing out that just as in life, we always have a limited view of any narrative and can’t hope to experience an event from every available perspective. This is why the search for universal values rather than universal stories is so important.

“We never take the visitor’s perspective, but more the protagonist of the story or the hero. Then the visitor can choose where to focus and how deep to go into the details. We focus on the story and those universal values and then it is up to the visitor, because we don’t know how they will be touched or how they will develop their engagement with the story.”

Dr Licia Calvi

To go back to one of our favourite quotes from WXO Founding Member and theatre director Martin Coat, people are either “skimmers, swimmers or divers”. How deeply they choose to immerse themselves is up to them.

Everybody’s A Hero (Even Bankers)

In the continuing debate about what constitutes a hero, Dennis Moseley-Williams had a neat idea about how to transform something as boring as the walk to a banker’s office into a Hero’s Journey.

“I work in the financial services industry. All of my clients sell stuff that can’t be touched. I’m trying to help them understand the difference between service and experience, because they’re commoditising themselves to death. It would be really cool if when you walked into these professional offices, similar to in a hospital when they say ‘follow the yellow line to the red line to the blue line and that’s where the X-ray is’, you could follow my story in pictures from the entrance to my office. In that timeline would be my personal aspirations, my heroes – Captain Kirk! – and photos of me from baby to toddler to teenager to me with my children. How do I position myself, or my clients position themselves? Who are they? You’re the hero. And I’m Gandalf.”

Dennis Moseley-Williams, consultant

When you understand someone’s backstory, you recognise elements of our own life – generating curiosity, empathy, and an altogether different kind of meeting.

Making A Mountain Out Of A Man In A Hole

The 12-step Hero’s Journey arc might be compelling when applied to someone’s personal narrative – but if you’re trying to create a positive experience, do you really want to include dilemmas and challenges as part of it? Event designer Kelly Vaught wasn’t sure.

“In my field of work it’s typically a branded experience within the context of a larger experience. The challenge is to try to follow the 12-step arc. The last thing I’m doing as a person who’s trying to be hospitable is creating tension or drama. I’m here to make sure everybody’s having a great time.”

Kelly Vaught, event designer

However, perhaps we can flip this model and turn a challenge into an opportunity for growth – or a man-in-a-hole into a mountain.

“I used to design according to the Hero’s Journey template in terms of the Kurt Vonnegut version – the ‘man in a hole’ story. And this is really simple: I flipped it around and turned it into a mountain. Do you want to go into a hole? No, thank you. Do you want to climb a mountain? Yes, please. You flip the challenge into an aspirational challenge.”

James Wallman, CEO, The WXO

Let The Story Guide You

When it comes to 12-step versus 5-steps storytelling models, perhaps one is better suited to the individual hero and the other the collective.

“The five steps make more sense for a larger story, or in film terms an ensemble cast. We could break down Star Wars – Luke’s arc fits the 12-step Hero’s Journey, but the five step makes more sense for the whole team.”

Dallas Burgess, filmmaker

However, Burgess worried that by focusing on fitting a story into a pre-existing structure, we risk interrupting the elements that make it work.

“You start forgetting about the natural flow of the story. The story will tell you what it wants, the story will guide you. Rather than trying to go technical with how you break it down, there’s an organic process to it that will guide you in the direction that the story wants to go. And often you’ll be pleasantly surprised, because the story will take over and now you’re just along for the ride.”

Dallas Burgess, filmmaker

Perhaps the best way to rule these structures is as a set of tools to unlock creativity, not a straitjacket to confine it.

“Of course, the creative process needs to come from the heart. But when I teach people storytelling, I say ‘these are the ingredients and these are the kitchen tools. But when you start cooking, you need to taste, you need to smell, and you need to feel. And sometimes if you get stuck, this model can help you.’”

Dr Moniek Hover

The creative process comes from the heart and stories live inside people. How you tell them might depend on their context, but their resonance comes from their core.

“The two models are entirely context-sensitive. When it is the story of an individual, having a 12-step arc makes perfect sense. Whereas you need a different kind of model when you are looking at a multiplicity of stories and voices. This reaffirms that stories ultimately live inside people. You need to design experiences around that.

My expertise is in working with children and what I often feel is underrated is that a story has to engage all the senses, not just one or two. How you tell a story can deal innovatively with these aspects only if you’re able to understand that stories ultimately live inside people. It’s not the format, it’s the way in which it comes through. Sometimes I think you can have very simple modes of storytelling. But if you do it well, the story will stick. The stickiness is the resonance, which if you’ve understood the core, you can translate creatively.”

Niv Subramaniam

The Superhuman As A Window To Humanity

It might be true that we find the superhuman heroes of Greek mythology unrelatable – but do we need an element of the superhuman to draw us into a story? Is the superhuman hero’s journey the “window story” that invites us to explore more deeply and discover more?

“I think part of what draws people to the Van Gogh experience is that there’s a recognition of a something that’s superhuman: the great art. But then through that story, you begin to embody it a bit more through different perspectives and it becomes much more of a human thing. Is it a continuation, not one or the other? Maybe it’s this attraction to something greater, to superheroes or gods, that draws you in – but the disclosing of a much more human story is what resonates.”

Brendan Brown, VP Strategy, George P Johnson

This also reminds us of Campfire 29 and its revealtion of how Superman is in many ways the ideal hero because on the one side, he’s superhuman; and on the other, he’s a lonely orphan.

Have Fun With Your Audience

Building on his comments in Campfire 30: How To Design For Flow about unleashing the inner child, creative director Steve Tiseo thought it was important to make each story an invitation for your audience to play.

“A lot of what we do is interactive experiences for demos or training, where it’s more about communicating the facts. How do we shape that to be more of an experience? For us, it’s mostly to try and make the audience play or have fun with it, even if it’s not the most playful material. I feel like if they have fun they’ll remember the experience better.”

Steve Tiseo, creative director

Even when your priority is to communicate the facts, there’s always room for story.

Do We Need Storytelling To Design Experiences?

As our storytelling mini-series draws to a close (for now…), Steel wondered how important it actually is when it comes to experience design.

“Frankly, storytelling isn’t my thing. So I’m interested in the touchpoints, the experiences that deepen or enrich meaning or significance, but I leave it to others to weave the narrative.”

Douglas Steel

However, he concluded that from the Hero’s Journey to the Seven Basic Plots to Wonderworks, the recent book by Angus Fletcher, that it’s worth expanding our knowledge of storytelling to see how it might amplify the experiences we design.

The WXO Take-Out

- Narratives are factual, stories are emotional. It’s important to know the difference when designing an experience – and that stories are what lead to transformation.

- As we previously heard in Campfire 29, empathy is the bedrock of how we relate to stories. Find the universal themes of a story, and your audience will recognise elements of their own lives in it – leading to a deeper emotional connection to a place, person, or experience.

- A “window story” can act as a gateway into more stories and perspectives. The important thing is to select those that will generate the most empathy and therefore hook your audience in, wherever they’re coming from.

- The 12-step Hero’s Journey arc works well for individuals, and the 5-step process for collectives. But ultimately stories live within people, not formats, so sometimes you have to let the story be your guide.

- How might you apply the storytelling models used here as a tool to leverage your creativity, rather than a straitjacket to contain it?

Interested in taking part in discussions about experiences and the Experience Economy? Apply to become a member of the WXO here – to come to Campfires, become a better experience designer, and be listed in the WXO Black Book.