What’s the opposite of a good idea?

If you said “bad idea” – well, in the spirit of the exercise, we don’t want to say you’re wrong.

But according to Rory Sutherland – Vice Chairman of Ogilvy, behavioural psychology champion and founder of Nudgestock – the opposite of a good idea can also be a good idea.

That’s because humans don’t run on logic – they run on what Sutherland calls “psycho-logic”. He believes we should be asking daft questions to uncover people’s unconscious motivations, then using the insights to make small tweaks that can have a massive impact on the way people think and act.

Because what we say isn’t always what we mean. Take the British, for example. In his excellent book, Alchemy: The Surprising Power Of Ideas That Don’t Make Sense, Sutherland exposes the gap between what the British say and what they mean:

What the British say: that’s not bad.

What foreigners understand: that’s poor.

What the British mean: that’s good.

What the British say: I would suggest.

What foreigners understand: think about his idea, but I should do what I like.

What the British mean: do it or be prepared to justify yourself.

What the British say: very interesting.

What foreigners understand: they are impressed.

What the British mean: that is clearly nonsense.

Understanding psycho-logic isn’t only about learning to beware of the British, however. It’s a crucial tool for being able to come up with radical solutions to massive problems that involve not huge physical changes, but small psychological ones. As Sutherland writes:

“It seems likely that the biggest progress in the next 50 years may not come from improvements in technology, but in psychology and design thinking.

Put simply, it’s easy to achieve massive improvements in perception at a fraction of the cost of equivalent improvements in reality.”

Rory Sutherland, Vice Chairman, Ogilvy

Just think about the places you’ve been where they’ve spent millions on the hardware and completely forgotten about the experience design.

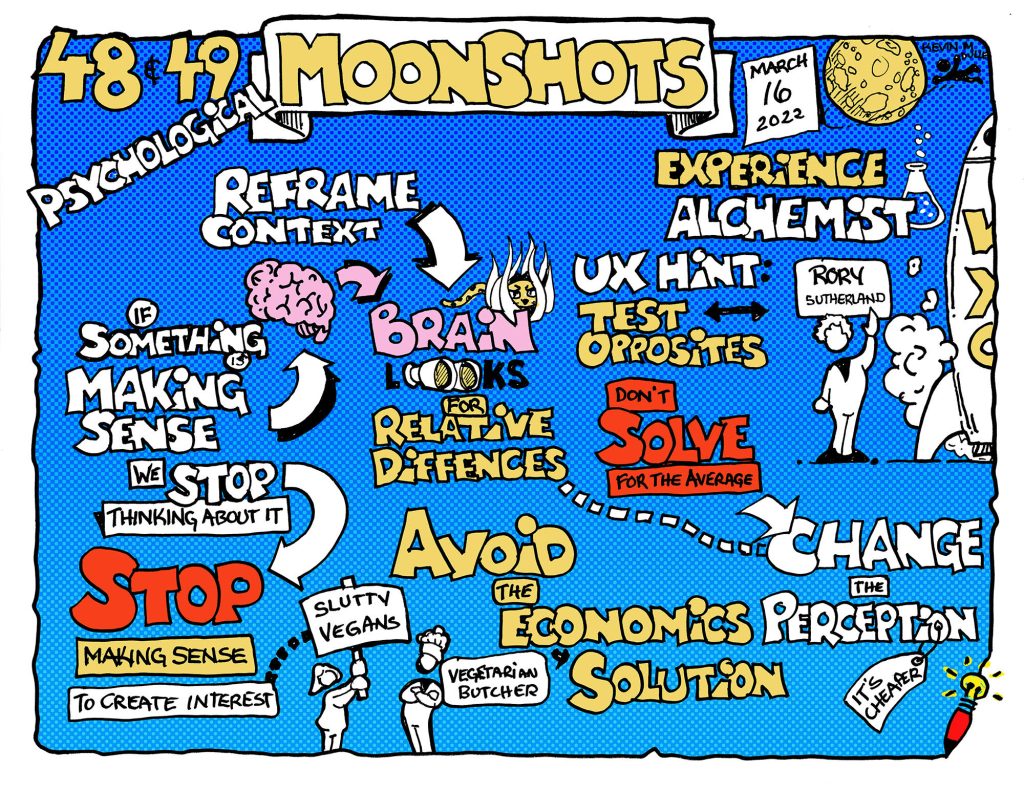

We think Sutherland’s non-sensical ideas could be pretty useful for experience designers in their quest to transform people’s behaviour and create experiences that go deeper, last longer and cost less. So we were delighted to welcome him – fresh off the back of doing a podcast with another very brilliant and very British treasure, John Cleese! – to share them in Campfires 48 & 49.

From slutty vegans to false positives via air fryers and toothpaste, here’s everything you need to become an experience alchemist.

1. Meaning And Value Are Determined By Context

We live in a society that prizes logic and looks to economists for conventional wisdom. But there’s something that economists get wrong.

Conventional economic models assume that individuals making a decision have stable preferences, perfect information and perfect trust. They know what they want, how much they want to pay for it, and they have absolute faith in the seller.

This is clearly nonsense – or there would be no such thing as advertising, behavioural science, nudge theory or marketing.

“You wouldn’t need any of the psychological facets that are necessary to make a business trustworthy, attractive, likeable, believable, or plausible.”

Rory Sutherland, Vice Chairman, Ogilvy

So why do economists hold to this? Because in economics, there’s no difference between the value a product has in the factory and in the human brain. We all have an internal value-o-meter that tells us what we should buy and how much we should pay. Perception and context have no part to play in our decision making.

This absolute belief in objective perception falls at the first hurdle, because evolution has not given us perception apparatus optimised for accuracy, but instead for survival. This means that humans are very changeable and unpredictable.

“If evolution has to make a call between accuracy and fitness, it will choose fitness every time. What makes us reproduce, what makes us make safe, and non-catastrophic decisions in the world do not necessarily come from an objective and accurate appraisal of reality.”

Rory Sutherland, Vice Chairman, Ogilvy

It’s more to our evolutionary interest to perceive relative differences in things than it is to perceive absolute differences. Take footsteps in a dark alley versus in a busy street, for example – one might make us tense, the other relaxed. Meaning, unlike essence, is contextually determined.

This video shows how our brain corrects objective reality for an imagined shadow, as in many cases it’s far better for survival to notice a difference between two colours hiding in the undergrowth than it is to be able to name the precise Pantone reference of a particular leaf. Objective reality isn’t useful – but our perception of it is.

When it comes to products or experiences, the same applies. Five dollars doesn’t have an objective value – we don’t experience the same pain paying $5 for a coffee as we do for upgrading to a better television, for example.

Nespresso machines are a brilliant device for reframing price comparisons – if you bought it in a jar, it would probably cost $40. But because you buy it in a pod, you can’t compare it, as we don’t know how much it actually costs – so we compare it to Starbucks instead and think “this machine is practically making me money!” And Rolls Royce stopped exhibiting at car shows because a $400k car looks really expensive next to a $60k one – but when exhibiting at yacht/jet shows instead, that car becomes an impulse buy akin to sweets next to a till.

British Airways changed their website so that when you asked for prices for an economy ticket, it also showed you the prices two classes up. They argued you couldn’t say what you were prepared to pay for the next ticket up until you knew what the economy ticket would have cost. What mattered was the relative difference, not the price alone.

2. Don’t Change Your Product, Change Your Context

Given that whether something’s valuable or not is perceived in a way that is not context free, we can therefore change the nature of an experience not by changing the experience itself, but the context in which it is perceived.

“There is no sensible distinction to be made in a restaurant between the value created by the man who cooks the food, and the value created by the man who sweeps the floor.”

Ludwig von Mises, economist

Austrian School economists like von Mises understand that marketing and advertising done well are part of the overall value creation process. To a neo-liberal economist, however, all advertising is doing is messing with perfect and stable preferences. But having a great product and not selling it well is the equivalent of serving Michelin-starred food in a restaurant that smells of sewage – you still won’t enjoy the meal.

Take the air fryer – because it was called a fryer and placed next to deep-fat fryers in stores, it was contaminated by association. Whereas if they’d called it “the air sauteur” (the French word for frying), it would have flown off the shelves years ago.

Sometimes you need to find the most sellable context in which to capitalise on a product’s strengths in order to maximise its potential. Look at Zoom – it succeeded over Skype because it was positioned as a video meeting (useful and polite) rather than a video call (annoying and intrusive). The pandemic also changed its fortunes. Before, having a video call was outlier behaviour, like having a Dr Pepper rather than a Coke – it required explanation. Now, it’s become the standard.

3. False Positives Are Tolerable, But False Negatives Are Terrible

We tend to assume the best way to change an experience is to change its objective reality. This would be true if we saw the world objectively to begin with.

When in doubt, evolution has taught us to do what you’ve done before, or what everybody else is doing. Habit is rarely optimal – but it’s very non-catastrophic. And evolution is principally interested in not doing anything that will kill you. Losses loom much bigger than gains in our imagination because of this.

All of us are descended from people who managed to survive long enough to reproduce by not making catastrophic mistakes. This is why we’re happier with false positives than false negatives – being slightly frightened of spiders might be embarrassing if they turn out not to be poisonous, but if we’re not frightened of them and they are poisonous, the results can be potentially fatal.

A lot of our decision-making is generated by this risk aversion – plus the total asymmetry of our perception to begin with! As a result, people don’t pay a premium for brands because they’re better, but because they’re less likely to be bad, as the supplier has more reputation to lose than someone you’ve never heard of.

“Brands are a guarantee of not-shitness. McDonald’s isn’t the best restaurant in the world, but it’s best at being tolerably enjoyable. None of that is true of Michelin-starred restaurants, which are a high-risk experience.”

Rory Sutherland, Vice Chairman, Ogilvy

4. The Difference Between The Proximate Why And The Ultimate Why

These asymmetries are everywhere, even though we’re always looking to imagine the world as symmetrical. This desire to make sense of the world also leads to us generating blind spots, as once we think we’ve made sense of something, we stop asking questions and move on. In fact, there’s often a real “why” behind the official or reasoned “why”.

“Not all the factors we are considering necessarily being visible to conscious introspection is a really important thing.’

Rory Sutherland, Vice Chairman, Ogilvy

If we use brushing your teeth as an example – people might say the reason for doing it is to maintain good dental hygiene. However, if you look at when they clean their teeth – before work, a big presentation or a date, for example – it becomes apparent that vanity is the real driver. That’s why the majority of toothpastes are flavoured with mint, even though it has no health benefits.

Early soap manufacturers knew this; they sold the main benefit of their product not as its ability to protect against cholera, but to protect against dying alone. Understanding the difference between the proximate why and the ultimate why is crucial to understanding our behaviour.

5. You Can’t Pre-Rationalise The Future

The only reason humans evolved a faculty of reason is to argue with other humans and defend our behaviour after the event. Therefore we don’t use reason to make decisions, but to post-rationalise them. Reason is a social tool, not an individual decision-making tool.

“The conscious brain thinks it’s the executive office, but it’s actually the press office.”

Rory Sutherland, Vice Chairman, Ogilvy

When we rely on reason, we ignore the face that we’re unpredictable creatures driven by our unconscious brain rather than our conscious brain – and that much of what we truly think is unknown to us.

In the same way, we find it easy to post-rationalise the past, and therefore think it will be just as easy to pre-rationalise the future using the data we have.

However, there’s much more entropy in the future. If you use data from the past to optimise what you do and demand evidence before you act, you’re therefore not playing with the full deck.

There are more good ideas you can post-rationalise than pre-rationalise – take Starbucks, bottled water or Dyson vacuum cleaners, for example. If James Dyson had said there was a market for a $700 vacuum cleaner in 1994, would have said he was mad – yet the product succeeded.

The taste of Red Bull was panned in original market research, but its challenging flavour helped impart a feeling of being caffeinated that helped cement its brand. And Five Guys managed to charge $10 for a burger in an outlet that looks no fancier than a branch of McDonald’s.

“Business has lost the art of testing things that you can’t measure, or testing things without evidence they will work. However, the really big discoveries won’t have this data.”

Rory Sutherland, Vice Chairman, Ogilvy

Enormous amounts of money are spent on trying to prove that business is a knowable entity – but moving forwards, we need a much higher level of experimentation and variants. Don’t just design for averages – design for outliers.

“Data science (tells you what’s happening) can still be used to great effect when you marry it to behavioural science (tells you why it’s happening) and creativity (tells you what might happen).”

Rory Sutherland, Vice Chairman, Ogilvy

It’s also worth considering that habits change over time – and while this may take a long time, it’s often more important to think about the stickiness of an idea as opposed to its growth. An idea, product or experience that initially seems absurd can only be rationalised and understood when we look back – so if we try and pre-rationalise it, we risk missing out on its success.

“In any new business a lot of new ideas grow really slowly, because people find it really difficult to take on board new habits. But the thing to look at isn’t necessarily the pace of growth. It’s to look at the level of stickiness. Nobody who got a mobile phone ever went back to not having one. Same for multi-channel TV. Once they had it, it was impossible to go back. And so one of the things we don’t look at enough with new innovations is how many people who actually make the step then become a convert.”

Rory Sutherland, Vice Chairman, Ogilvy

6. Don’t Just Test The Obvious: Test The Opposite

In physics, the opposite of a good idea is wrong. But in psychology, the opposite of a good idea can also be a good idea. So sure, test the obvious thing to do in a situation – but also make sure to test its opposite, as this is where the really radical, paradigm-shifting innovations can be unearthed.

“Don’t just test the obvious – test the opposite, and things that don’t make sense. When those things succeed, they succeed disproportionately much.”

Rory Sutherland, Vice Chairman, Ogilvy

For example, we assume that we want our experiences to be as frictionless as possible – but sometimes friction can be good. Take a hotel check-in: you can fully automate the whole process so it’s low friction, or you can have someone take you to your room and make you a cup of tea while you fill out the forms, so it’s high friction. The brain processes both as being fantastic.

Similarly, extracting a gift from several layers of Nana’s sellotape might feel like a chore, as well as being inefficient and wasteful – but not only does it create anticipation and release dopamine, it signals that the gift has value and the person receiving it was worth the effort.

You’d think the best way to sell something would be to tell people that it’s amazing and loads of people want it – but sometimes it’s better to do the opposite.

“There are two ways of selling something: to say loads of people have this so it must be good, or that not a lot of people have this so it must be good.”

Rory Sutherland, Vice Chairman, Ogilvy

Pigalle Tavakkoli experienced the power of reverse psychology first-hand, when she drummed up interest in a 2,000-person festival tent by training marketeers to find cool-looking people and tell them not to come. Soon people were digging holes to try and get into this tent.

7. If You Have To Change Perception Or Reality, Always Choose Perception

We tend to think that to increase something’s value, we need to change the properties of the thing itself. For example, if you want to make a train journey better, it stands to reason that you should make it faster.

However, as we’ve learned, our reason is often flawed, and objective reality isn’t as valuable as our perception of it. We don’t need to change the objective reality, just the nature of that reality – and the great news is, solving a psychological rather than a physical problem is deeper, more enduring and less expensive.

- We could spend millions trying to engineer a slightly faster train – or we could just make the experience of the journey better, perhaps by having a really amazing food cart on board.

- We could try and teach children all the traffic bylaws of the land – or encourage them not to walk on the cracks in pavements because they’ll get eaten by bears. This makes no sense at all, but in fact, it’s much more effective than telling them to watch out for traffic – because children don’t pay attention to traffic, but they do to bears.

- The screens you order through at McDonalds probably don’t reduce your wait, but there’s a subtle difference between time we spend waiting for our food once ordered, and time spent waiting to order. Although the time isn’t reduced, how we experience it is. Uber did the same by adding a live map to reduce the state of uncertainty while you’re waiting for a taxi to arrive. By doing this it reduced the irritation quotient, not the nature of time itself.

- Beyond Meat might not be technologically groundbreaking, but it stands apart from other vegetarian products as rather than making its message all about self denial, as previous products had, it doesn’t compromise and makes a confident statement about being even meatier than meat. The same goes for Slutty Vegan, a vegan fast-food joint in Atlanta that has no pretensions about being healthy.

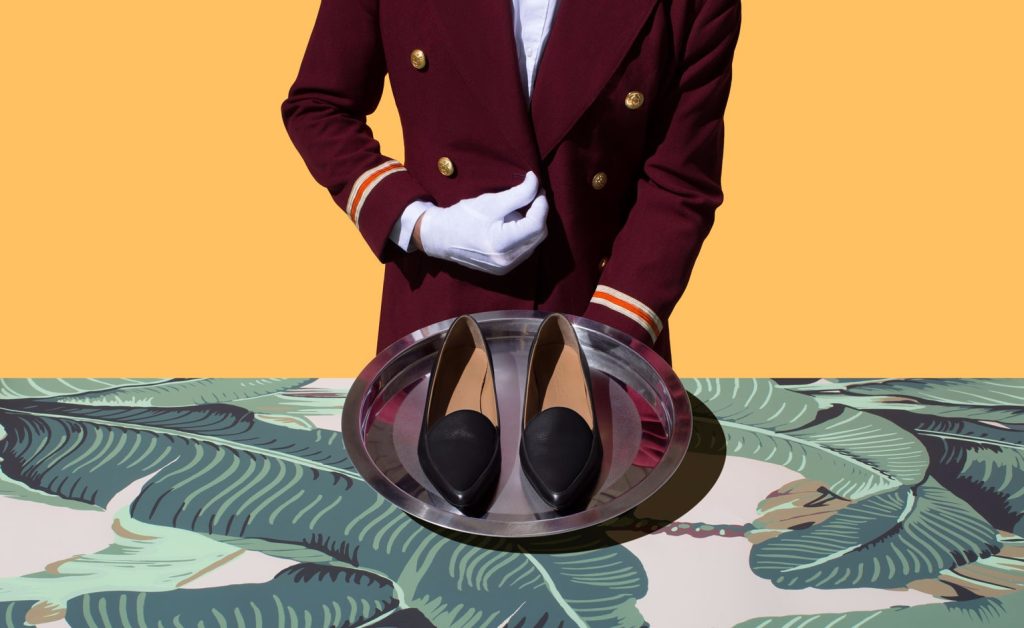

- The Magic Castle Hotel is always one of the top 8 or 10 hotels in Los Angeles on TripAdvisor, despite the fact that it looks nothing special. And part of the reason is that they’ve very cunningly done things which no other hotel can be bothered to do. They have a popsicle hotline next to the swimming pool, so if ever you’re sitting by the pool, you can pick up this red telephone and order free popsicles. When your laundry is returned, it’s wrapped in brown paper with a sprig of lavender on top. They do four or five really effortful, meaningful behaviours, which no other hotel does, and because no one was expecting it, they love it. Having a clean minibar is table stakes. It doesn’t make a difference, but doing something that no one expects you to do. That’s magic.

People think that if you solve the psychological problem, you’re somehow cheating – but in fact, the psychological problem is the core problem and the physical problem is just its proxy. The extraordinary, unpredictable things we do can make an extraordinary difference. And this is where true alchemy comes into play: it creates value out of nothing.

The WXO Take-Out

We might tend to see what we do as part of a distinct category or sector. But whether we’re designing for customers, employees, guests or visitors, at heart we’re designing for people.

Understanding things from their point of view, and looking to improve not the objective reality, but the perceived reality of an experience, can help us to find solutions that are deeper, cheaper and longer-lasting. The job of an experience designer is to provide new perspectives and be able to look at the same thing three different ways.

“A change in perspective is worth 80 IQ points.”

Alan Kay

People may like the idea of choice – but they don’t like the reality. They need someone to design that for them. This is where experience designers come in.

“Work in this area has huge potential to solve the problems in our environment, improve quality of life and increase profitability, without being in conflict.”

Rory Sutherland, Vice Chairman, Ogilvy

Want to be part of the most inspiring experience conversations in the world? Apply to become a member of the World Experience Organization here – to come to Campfires, become a better experience designer, and be listed in the WXO Black Book.