You’ve likely got a few tried-and-tested story shapes that you return to when structuring the narrative of your experiences: the classical Aristotelian three-act structure, Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey, Freytag’s pyramid…

And while there’s nothing inherently wrong with these story designs, we don’t have to be slaves to them. Today, we’re living in a new reality where the old rules don’t apply.

Immersive storytelling needs more than a conflict-based structure to come to life. And new technologies, from the metaverse to Web3 to XR, are widening the possibilities of how we tell stories that really land with our audience.

At the WXO, we’re big believers in supporting the pioneers changing how we tell stories – see our previous Campfires on The End Of Storytelling with Stephanie Riggs, Integrated Storytelling with Klaus Sommer Paulsen, Transmedia Storytelling with David Bassuk, and Story For Open-World Experiences with Nick Moran, for starters.

So it was a delight to welcome storytelling iconoclast, XR evangelist and Reality+ founder Christopher Morrison to the WXO Campfire, where he shared several story structures designed for today and tomorrow’s new media landscape.

In this report, you’ll learn:

- How the Hero’s Journey might be holding your storytelling back

- Why psychology is NOT the only basis for story

- 4 new story structures to experiment with in your experiences

- An entirely new way to think about story…

Here are our top takeaways from Morrison’s mind-blowing presentation. To watch the full recording or join the interactive discussion at future Campfires, apply to join the WXO today.

All Stories Either Reinforce Or Challenge The Status Quo

“Narrative informs culture and policy.”

Tabitha Jackson, Head of Sundance

In other words: all stories either reinforce or challenge the status quo. We have a massive opportunity, particularly in newer experience forms like immersive theatre or video games, to do things differently.

But currently, we’re messing it all up by:

- Using old models that don’t fit the tech we’re telling stories with.

- Using old, harmful models that are designed to reinforce, not challenge, the status quo.

- Continuing to follow the three-act structure and Hero’s Journey, which both fit the criteria for the above.

- Insisting on using conflict to drive our stories.

The traditional three-act structure is built around a central conflict, with the second act depending on rising tension and action. (Morrison points out that this represents the male orgasm, from flaccidity to climax to sleep…)

Eff The Hero’s Journey!

There are lots of problems with relying on the Hero’s Journey as our sole story structure. For starters, Joseph Campbell is a man who taught at a women’s college who believed that women couldn’t be the Hero.

Furthermore, Campbell called it the “monomyth”. Every single culture on the planet has its own myths – as well as music, dance, and ways to kill each other – so to stick the word “one” in front of “myth” is a problematic action that reduces all culture down to one thing. The slew of books out there telling us its the best story structure out there, from Will Storr’s The Science of Storytelling to Rupert McKee’s Story, reinforce this problem.

Psychological-Based Storytelling Vs Sociological-Based Storytelling

So what types of stories does the monomyth give us? They are all psychologically based, which means they are:

- Obsessed with immersion. They insist that we must understand the main character’s motivations and inner workings as seen by their actions, and “identify” with them.

- Obsessed with realism – as if this is something that really exists…

- Obsessed with change.

- Obsessed with psychology.

- Obsessed with catharsis. We have to try and match our own emotions to what we’re experiencing.

But psychology is not the only way we experience the world. We experience it through lots of other, equally valid lenses, including but not limited to…

Emotional reality, images, metaphor, poetry, pattern, rhythms, music, gesture, Gestalt, comparison, contrast, sociology, anthropology, trauma, kinesthetics, aesthetics, harmonics, science, mathematics, myth, legend, folklore, auditory, taste, fears, dreams, architecture, belief, magic, ASMR, sensation, logic, chaos, structure, ecology…

These are all also equally valid lenses from which to tell your story, as opposed to just examining the internal psychology of a single character. If we look at sociological-based storytelling, for example, we focus instead on examining the structures that lead a character to do what they do, not their internal motivations.

Take the TV series Game of Thrones, which is an example of sociological storytelling. The “main character”, Ned Stark, ends up with his head on the floor halfway through the series, as it’s what society demands, and the concern with how society functions is the main preoccupation of the story. When the TV series went beyond the books it was based on, it began to fail when the creators fell back on psychological storytelling.

Beware The Idiot Plot

Another problem with psychological-based storytelling is that it leads to one plot: the idiot plot, as explained by David Brin and Roger Ebert.

The three-act structure and its rising tension in Act Two isolates our main hero, as we have to keep raising the stakes – and for our main character to be the only person who can solve these escalating problems. However, this turns the world and all the characters in it, except for our hero, into idiots who either end up dead or given a side plot to help solve a problem for the hero.

This is insidious, because it implies that all the usual systems that could be called in – the police, government, etc – are filled with idiots and dysfunctional.

Beyond The Monomyth: 4 New Story Structures

But! There’s some good news. We don’t have to be slaves to these story structures. There is another way – or ways…

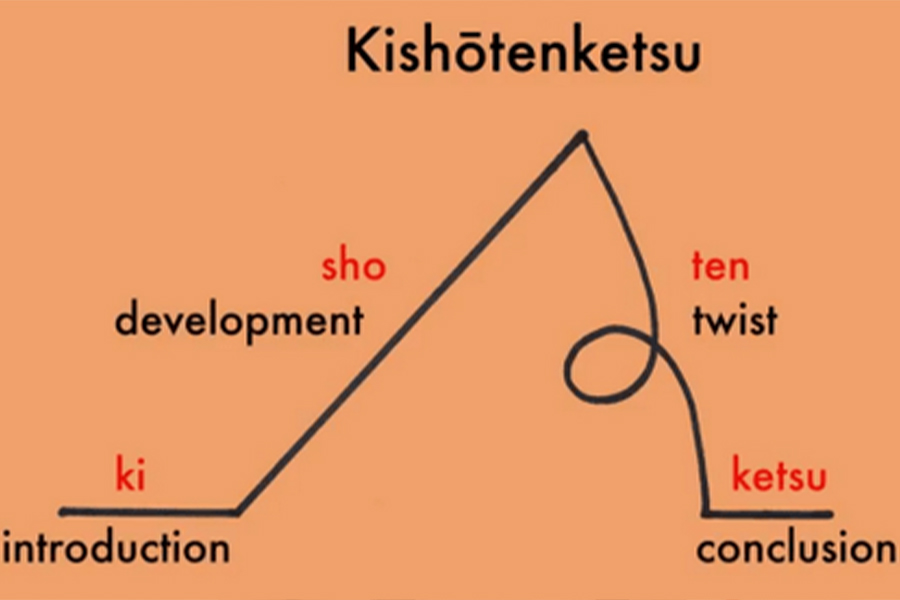

In the Japanese Kishotenketsu story structure, for example, the tension doesn’t have to escalate in the second act. Instead, the story can develop through procrastination, going backwards, fractally, eating itself, repetition, or any number of other methods. You’ll commonly see this kind of structure in manga and Japanese comics, as well as the Super Mario game series.

Morrison isn’t the first to notice the need for new story structures. Forerunners like the science fiction author Ursula K Le Guin and Jane Alison, the author of Meander, Spiral, Explode, have codified this thinking in recent years. Alison says that Aristotle’s three-act structure was specifically designed to explore Greek tragedy, a specific media from 3,000 years ago – so why did we continue to apply it after?

Instead, Alison looked to nature for new structures to apply to writing stories. Here are four that Morrison outlines:

- The Wave

In this structure, the peak of the story is in the middle, after which point the story collapses in on itself. There is as much story in the front as in the back. Take the classic Psycho, for example – the climax occurs with the shower scene in the middle of the movie, when the genre flips from heist into horror and we get a new main character.

Other examples of the Wave: Truly, Madly, Deeply, I Am a Ghost, Palm Springs, In Bruges, Gone Girl, The World’s End, Vanilla Sky, Parasite, The Celebration, Les Diabolique, Bullet in the Head…

- The Wavelette

These stories consist of a series of ripples. Where the three-act structure rises to a peak that matches the male climax, the wavelette more closely mirrors the female climax: many small peaks adding up to lots of information. In the third series of the TV show Atlanta, for example, the four main characters don’t appear in ten of the episodes, but the story still functions as we understand that what we’re really exploring is the central question of what it means to be Black in America.

Other examples of the Wavelette: The Square, Euphoria, Fleabag, 5 Meters per Second, Paprika, most of Truffaut and Bergman’s catalogue…

- The Spiral

Spirals play with time displacement, looping around a timeline and ignoring the cause/effect relationship. They can also spiral out from or back towards a place, and experiment with mirroring and repetition. In the film In the Mood for Love, for example, the characters aren’t allowed to consummate their love or say the word to anyone else, and are only allowed to express it in the hallway of the building they live in and the stairway to a noodle shop. There’s a poetic or song structure that can be applied as scenes. You may have been taught in film school to never return to a set. Spirals ask what might happen if we do, as it can be filled up with more perspectives.

Other examples of The Spiral: Walk the Line, Amadeus, Election, Everything Everywhere All at Once, Russian Doll.

- The Radial

In this story structure the climax is the first scene, and the story explodes from there. It’s concerned with one moment in time that is frontloaded, with every scene a radial or reference from that. In Rashomon, for example, a murder-rape is reexamined from three points of view, and gives you no truth at the end.

Other examples of The Radial: The Sweet Hereafter, Dunkirk, Atlanta, 1917, Paths of Glory, The Last Duel, TImecode, Groundhog Day, Memento…

How To Choose & Use Your Story Structure

All these story structures – including the Hero’s Journey – are tools in your toolkit, to be applied when they are the best fit for the story you’re trying to tell. Morrison’s frustration comes from when they become institutionalised and codified, leaving no room to tell new stories.

“I don’t care about the dead thing: I care about the writer doing the next thing.”

Christopher Morrison

Where a lot of narrative storytelling in the West has focused on a call and response structure, the story structures above are more diffuse and can lend themselves better in a live environment or for when you lose authorial control. They’re a container that allows you to break this cause and effect, and do well in modular situations. This is particularly useful for stories, which are a multitude rather than singular – as creative director Julian Rad says, “I think of it not as story, but as possibility: what possibilities am I creating for my audience?”

This kind of storytelling might not yet quite be a movement, but people are already thinking about these things in different silos. Many of these ideas have already been pioneered by women like Le Guin, Alison, Christy Dena and Gwen Loab. As Le Guin says:

“It sometimes seems that [the heroic] story is approaching its end… some of us think we’d better start telling another one… The trouble is, we’ve all let ourselves become part of the killer story, and so we may get finished along with it. Hence it is with a certain feeling of urgency that I seek… the untold one, the life story.”

Ursula K Le Guin

If we want to reach a new and better future, we need to examine the stories we tell that will get us there.

The WXO Take-Out

We’re excited by the idea that “all stories reinforce the status quo or challenge it”, and that therefore we can impact society by the stories that we tell. If we can change the monomyth by moving away from conflict as the central theme and towards collective transformation, we can change the story of humanity.

We no longer have to be chained by limiting structures. Instead, we can use these new structures – and innovate our own – to create better stories and better experiences. Each story structure is one tool, which we can layer into our experiences to achieve our desired effect.

So next time you’re designing an experience, ask yourself:

- Which story structures do you currently rely on when building your narrative?

- Is your story better suited to psychological-based or sociological-based immersion?

- Which of the four new structures – Wave, Wavelette, Spiral or Radial – might be a better container for your story and audience?

Want to come to live Campfires and join fellow expert experience creators from 39+ different countries as we lead the Experience Revolution forward? Find out how – and the current speaker line-up – here.