We all want an easy life, right?

Well, perhaps. But what we want isn’t necessarily what we need. And when it comes to experiences, if the goal is transformation, the last thing we should be seeking is ease.

The presence of friction is one of the key differences between a service and an experience. A service is designed to remove friction – but in the pursuit of becoming seamless, it also risks becoming unremarkable, unmemorable, and bland. In an experience, however, friction is an essential ingredient: when we overcome a challenge, we grow and can ultimately be transformed.

This insight isn’t just based on intuition: it’s the repeated outcome of experiments in psychology, storytelling and neuroscience. Look at Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi’s definition of flow, which states that:

“The best moments usually occur if a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile.”

Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi

Or Herbert Benson’s four steps to flow, which start with struggle. Or even the Hero’s Journey, which begins with a Call to Adventure along a Road of Trials littered with Enemies.

So ahead of neuroscientist Dr Paul Zak’s Campfire on the Science of Extraordinary Experiences, we decided to delve deeper into the neuroscience of flow and ask ourselves how we might design for struggle – or even disaster – to deepen the resonance of our experiences and create the conditions for happier, healthier and changed people.

The WXO’s CEO, James Wallman, shared some of the principles of flow that inspired his second book, Time and How To Spend It, before we dissected how we might bring them into our own experiences. Here’s what we discovered.

Time Design Is An Essential Skill

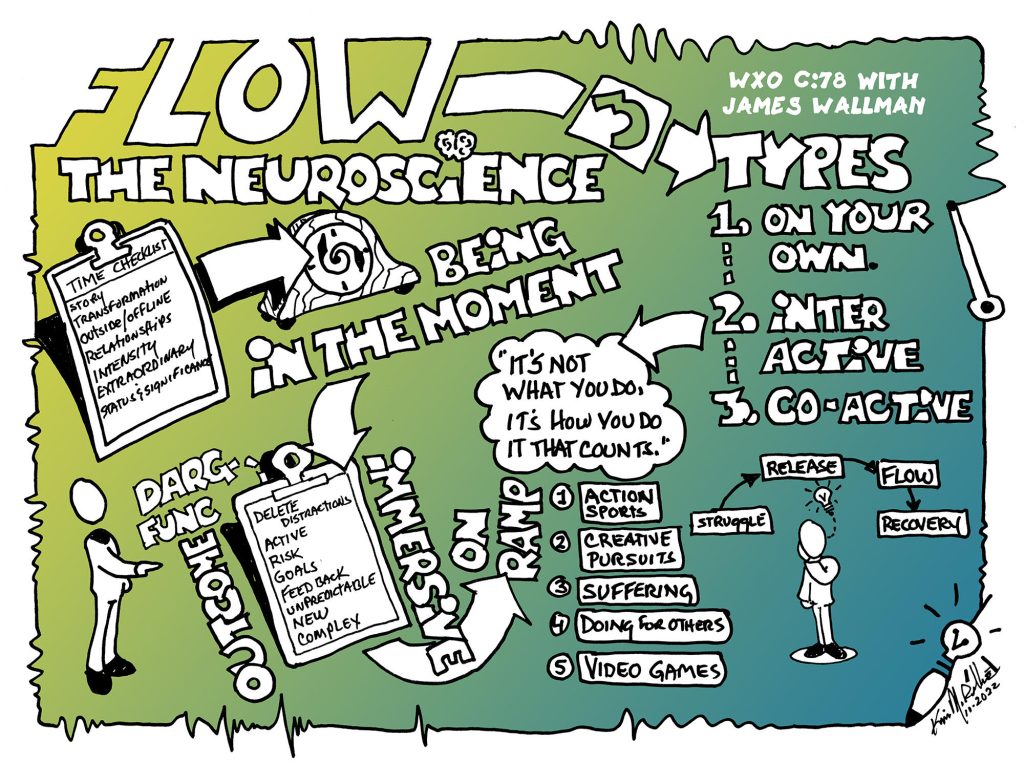

In Time and How To Spend It, Wallman boiled down the research he found across disciplines including psychology, neuroscience and economics into a seven-point checklist to guide people towards having richer, happier days: the STORIES checklist.

Story

Transformation

Outside & Offline

Relationships

Intensity

Extraordinary

Status & Significance

This list can be flipped to tell us not only how to spend our own time, but how to design it for others. And the “I” of the list, Intensity, dovetails nicely into the concept of flow.

Flow was coined by Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi – for a more detailed dive into the conditions of flow, see Campfire 30: How To Design For Flow. He said that:

“The popular assumption is that no skills are involved in enjoying free time, and that anybody can do it. Yet the evidence suggests the opposite: free time is more difficult to enjoy than work… leisure … does not improve the quality of life unless one knows how to use it effectively, and it is by no means something one learns automatically.”

Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi

The same holds true of experience design – it’s harder to design an impactful experience than you might think. Understanding flow, or immersion, or intensity, is the key to elevating an experience from the ordinary to the extraordinary.

What Are The Conditions For Flow?

Essentially, flow refers to a state when you’re totally absorbed in the moment. It can fall into three categories:

- Individual flow, where you’re on your own

- Co-active flow, when you’re experiencing flow alongside someone, for example running beside them

- Interactive flow, where you’re co-creating the conditions for flow, for example singing in a choir or playing a game of football

Wallman has developed the DARG FUNC checklist that outlines some of the conditions to create flow, based on the findings of Csikszentmihalyi and others.

Delete Distractions (e.g. taking your phone away, as per Secret Cinema)

Active (e.g. being physically active or creative)

Risk (e.g. skiing, sailing, karaoke)

Goals (because it’s good to know where you’re trying to get to…)

Feedback (…and if you’re getting there)

Unpredictable

New

Complex (the combination of the above three keeps us on the edge of our seat. E.g. foreign travel)

We’ve discussed several times whether flow is the same thing as immersion – see Campfire 20: The Immersive Firestarter for insights from immersive pioneers including Maël Magat, Stephanie Riggs and Noah Nelson. We’re in an age of “immersive-washing”, where a glut of new experiences are claiming to be immersive. An experience can be immersive in design, but to share the commonalities of flow, it must also be immersive in outcome. As Abraham Maslow said, “it’s not what you do, but how you do it”.

The Significance Of Suffering In Flow Experiences

However you define it, one of the more intriguing and seemingly contradictory aspects of a flow experience is that it should involve a degree of suffering. Take Steven Kotler’s five on-ramps to flow, for example:

- Action sports

- Creative pursuits

- Suffering (runners’ high)

- Doing for others (helpers’ high)

- Video games

Or the work of Herbert Benson,a professor of mind/body medicine at Harvard Medical School. In his 2003 book, The Breakout Principle, Benson mapped out the four stages of any flow experience:

Stage one: struggle. It could be physical or mental, like running a marathon or climbing a hill, playing chess, solving a complex problem, or creating a presentation.

Stage two: release from that struggle. That could mean taking a break, like sitting down for a rest, or, if it’s a mental problem, getting up and walking away from the computer for a bit, listening to music or having a bath.

Stage three: flow. This is what Benson refers to, following psychologists like William James and Abraham Maslow, as a ‘peak experience’.

Stage four: recovery. When a person comes down from the inspiring, energetic, and yet also physically, mentally, and emotionally draining high of flow.

These four stages also share the same shape as the Hero’s Journey. At the beginning, right after the hero has crossed the threshold, she goes through difficult tests on the road of trials. She has to overcome obstacles and enemies, create allies, and learn difficult skills. That sounds like a lot of hard work – struggle even. And Benson says that struggle is the essential launchpad for a peak experience.

Next, at the end of the road of trials and at the top of the arc, the hero has the ultimate ordeal. She enters the innermost cave, slays the dragon, and gets what she came here for: the reward. And so, in some sense, she’s released from the burden of her quest – she’s achieved it. In any hero story, there’s a pause here. After the storm of struggles on the road of trials building up to this final, huge, whacking great thunder crack, there’s a moment of calm. Indiana Jones has the treasure. Bilbo has a hold of the ring. Moana has the heart of Te Fiti. Look at this phase alongside Benson’s model and it sounds a lot like a moment of release and its reward, flow.

Then, in the final stage, the hero makes the return. She comes home, reintegrating what she’s learned and sharing her newfound reward with the world. Because of her heroics, everyone can rest easy, sleep well, and live happily ever after. Doesn’t that sound like a chance for recovery?

In short, Benson’s model:

1. Struggle > 2. Release > 3. Flow > 4. Recovery

The Hero’s Journey:

1. Road of Trials . . . Ultimate Ordeal > 2/3. Reward > 4. Return

When designing an experience, we should therefore ask ourselves if we include all four of these stages. An experience might contain “fake flow” – for example, the total absorption of getting lost in the doomscroll of your phone screen – but true flow gives you a stronger sense of who you are afterwards, and is a meaningful and worthwhile use of your time.

Hackathons are a fantastic example of Benson’s four stages, for example, as Melody Renaud pointed out. First, participants are given a challenge to overcome; the release comes in finding a way forward; the flow is in executing and pitching the answer; and the recovery comes in the connections you find afterwards, with people often founding companies or starting projects together.

Deliberate Disorientation

Kerrie Fraser designs immersive training experiences in which she and her team deliberately overload participants with information.

“We load them with a mission, story and different ways to explore it. Their brain explodes, and that’s where the learning starts. Once they make sense of it, they get the release, the flow comes from exploring and achieving, and the recovery is remembering. People are nervous of the struggle, but it really works.”

Kerrie Fraser

This “deliberate disorientation” can be a powerful way to introduce people into your experience and prepare them for struggle. Think of the way in which Punchdrunk purposefully wrongfoot you on the way into their experience, or how thrilling escape room The Drop asked guests to sign a waiver before entering – something Calypso Rose saw in action when organising a team outing there, when one of her colleagues was too scared to sign!

Embrace A False Start

Another way of disorienting people could be to create a “false start” to your experience that creates an awkward and uncomfortable atmosphere, before dispelling it. Cj Holden gave an example of some induction training at Morgans Hotel Group that did just this.

“The facilitators were rude, spelled names wrong, and yelled at people to sit down – they basically did everything to make it seem like a company you don’t want to work for. After 10 minutes the GM would come in and yell at them, before taking participants on an ethos tour of the hotel that ended in a party. The aim was to demonstrate that we’re not that, we’re this. The initial group experience felt horrible, but they came out the other end safe and comfortable.”

Cj Holden

…And A Twisted Ending

You could also disorient people at the end of your experience to make it more memorable and effective. Pigalle Tavakkoli gave an example of the theatre company Shunt Collective, who ended a show by revealing that a parallel group had just been through the same experience as you without your knowledge, before making you participate in a whole group challenge.

“There was a twist at the end: everything wasn’t what you’d thought.”

Pigalle Tavakkoli

Tavakkoli also points out that when designing for disaster, there’s a fine line between thrill and fear. She previously worked on a series of events with Brendan Walker, a scientist who works in amusement parks, to break down the different emotions that lead to a thrilling experience, such as frisson and suspense, as opposed to a frightening one.

Create A Common Enemy

A personal setback can feel like an insurmountable crisis: but a group challenge can provide a common enemy to unite against and overcome, and become a powerful bonding event.

“Different people face struggle differently. Some people have a growth mindset, and others want to shy away – it’s fight or flight. A group struggle is amazing because of this. Disaster is one of the most powerful events that brings strangers or even those who hate each other together. So can we design for disaster?”

Mike Gunawan

When we have to work with others to make the most of our complementary skills, it brings us together. And when we’re trying to build a genuine community, this co-reliance and trust is much more powerful than simply having a good time together. Think of the Covid pandemic: one of the silver linings is the way in which it united humanity around a common goal.

Creating a space where people feel safe to fail is also an authentic way of designing “disaster” into your experience. Holden creates corporate events and unconferences where attendees have to pass a pre-selection process to attend. Once they’ve overcome this initial struggle, they then have to bring something to share with the group – something that caused a lot of stress for some people.

“About 20% of people were really struggling with it. The release came in getting together and realising that we were all in the same boat and there was no pressure to perform.”

Cj Holden

The WXO Take-Out

Insights from neuroscience may be interesting – but they’re especially so when we can actually break them down and use them as a tool to make better experiences that make people feel more alive, happy and transformed.

By looking at Benson’s four stages of flow, we can play with elements such as struggle to realise how we already employ them in our own experiences, as well as where we might be able to do more to improve them.

So next time you’re designing an experience, ask yourself:

- Does your experience follow the four stages of flow: struggle, release, flow and recovery?

- How might you “design for disaster” within your experience?

- What “common enemy” might you unite your audience behind?

To see the full line-up for the WXO Campfires Season 5, click here.

To apply to join the WXO and attend future Campfires, click here.