What does embodiment mean in the immersive and experiential field? And what does embodiment mean in immersive work?

Somatic practice – attuning to the mind-body connection – is a powerful tool to answer these questions. In this Campfire Marissa Nielsen-Pincus, Associate Artistic Director at Third Rail Projects, shares how by developing deep awareness of one’s own ever-shifting internal landscape, we gain the capacity to attune to, connect with, and shape the experiences of others.

Third Rail Projects are known as makers of immersive and site-specific experiential performance characterised by its intimacy for both small and larger audiences. Their work is often movement based, but also includes text and audience interaction. When Third Rail started getting into the experiential field, Nielsen-Pincus started to notice that the work she does as a somatic practitioner was incredibly relevant in immersive performance.

In this Campfire you’ll learn:

- How somatic practices offer a gateway to the deeply personal: when met in an embodied way, a transformation occurs. One is no longer an observer on the periphery. This is when the magic of immersive work can occur.

- The 6 key tools you can borrow from somatic practice to connect with your audience in a more profound way.

- How to blur the lines between performance and our own realities, where embodied experiences, senses, memories, and personal associations intertwine with the themes and narratives to weave multiple layers of meaning into the fabric of an immersive journey.

What Is Somatic Practice?

Somatic practice encompasses a lot of different modalities that are all rooted in deepening the mind-body connection. It has a broad spectrum of applications including dance, yoga, theatre, physical and occupational therapy, bodywork, visual art, music, and more.

Nielsen-Pincus studied Body-Mind Centering®, an experiential study of the body, movement, and consciousness founded by Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen with embodiment at its heart. Anatomy, physiology, evolution, and developmental movement are explored through movement, touch, voice, breath, and consciousness. This creative practice invites discovery of wisdom and organisation within ourselves and builds our capacity to trust and integrate our own body-mind experience.

“The modality that I practise is an experiential study of the body of movement and consciousness, and embodiment is really at its heart. That means studying anatomy, physiology and the evolution of movement through an experiential process.

Marissa Nielsen-Pincus

It’s embodied in our muscles and our glands and our nervous system, and our fluids and brains and sensors, and using movement and touch and visualisation and images and imagination and sound and breath and awareness to learn. It’s a process of deepening your trust in your own experience.”

Embodiment & Somatic Intelligence In Performance

The word “embodiment” gets used a lot when talking about experiences, but Nielsen-Pincus prefers the definition of giving body to the spirit, first used in the 15th century, and to make concrete and perceptible.

This translates into immersive work on a macro level as a design principle. How can we design the audience experience so it’s synonymous with or a metaphor for the themes, conflicts, questions and narratives that an experiential work is built around? This relates to the production design, choreography and script, and the audience’s physical experience of the show.

On a micro level, how do we make the audience’s physical presence in the performance matter, and feel like it affects what happens? How can we listen and respond to our audience physically?

“All of this started to really give me language to explain and express what I feel happens in performance. It’s the way that we breathe, blink, meet each other’s eyes or look away, It’s our posture, our physical tone, our facial expressions or shifts of weight. All of these can be listened to and responded to within a performance experience.”

Marissa Nielsen-Pincus

This kind of reading and responding happens naturally in everyday life: we’re all attuned to each other and don’t even notice it. But in the heightened state of performance, we have to think about it, and these tiny moments somehow become very powerful. When these physical processes are listened to and acknowledged, something deeper starts to happen within us.

Nielsen-Pincus developed “the proximity game” to give a window into how powerful this somatic work can be and show how much care we need to take with our audiences. You stand on the opposite side of the room to a partner. One person is still, and the other slowly approaches. As they do, both of you pay attention to the feeling of a shift in the relationship.

Sometimes that might feel like you’ve gone through an invisible threshold: you might feel the tiniest flutter of your heart, or a change in your breath, or a shift in your weight, or the tension in your body change, or the breaking of an eye contact, or a blink, smile or laughter. All these are a sign that something physiological is happening in our bodies as we process this change in proximity.

This exercise is all about attuning and being present. It shows how intense it can be to interact with a stranger: the eye contact is intense, the proximity is intense, the slow approach is intense. Being in charge of someone else’s movement, or having someone be in charge of your movement, can be intense. If we pay attention to how our body reacts, they are all physical cues that something deeper is happening within us.

“To me this exercise is an amazing reminder of how much is going on between two people without any context or narrative.”

Marissa Nielsen-Pincus

It’s important to note that when you notice shifts in your partner – their breath, their posture – you might know that something’s happening, but you don’t necessarily know what those shifts mean: if they’re uncomfortable or excited, enjoying it or really unhappy. These are specific to that person. However, we can still respond to and acknowledge these physical shifts.

6 Somatic Tools For Experience Designers

Nielsen-Pincus has defined the following key tools from her work with Third Rail that can be applied in various types of performance or experience. They are so simple and small that we might not even notice them in everyday life, but somehow in the context of performance they come to life.

- Directing and guiding the audience with your body / non-verbal communication. Many Third Rail performances have a curated flow from one scene to the next where they need to move people to the right place. If the performers don’t use non-verbal communication to tell the audience this, it can create an unhelpful layer to the experience.

Through something as similar as moving your sternum in the direction you want someone to move, people will understand what you mean. Just as with horses, if you’re clear and confident about where you point your body, people will respond. - Eye contact. Another aspect of non-verbal communication is where we put our focus, so we don’t have to tell somebody where to look. We can use our eyes to direct attention as a performer, and this often gives the audience the space to discover and get curious.

Eye contact can easily be overused, but at the same time is one of the most powerful bonding experiences we can have with another person. By occasionally looking away and giving them some space, we can find those moments to reconnect. Some people will get lost in your eyes and others need more space to make some decisions.

Another aspect of eye contact is how we do it: we can laser our vision into someone which feels very predatory and intense, or we can open up our peripheral vision to take in more of them and the wider space, which can be a powerful tool when you’re in a large space with a large group of people to navigate. - Spatial relationships. There are a lot of power dynamics and status relationships at play in our spatial relationships. How close are we to each other? Are we side by side, around a table, or in a circle? Behind or in front?

- Mirroring. This is a really profound skill and tool for connecting. In body-mind centering they use the term “meeting someone where they are”, which means matching them as a starting place – physically and somatically matching their tone. We can meet their posture, their energy, the way they greet us with their eyes, the way they’re breathing. It’s a powerful tool for connecting with someone by making them feel heard and acknowledged and building towards something.

- Breath. Breath is one of the few places that is both autonomic and somatic. If we don’t think about it, our body will keep breathing. But if we pay attention to our breath, we can consciously change how we’re breathing: we can slow it down, we can deepen it, and we can speed it up. Changing our breath has a really profound effect on our autonomic nervous system. So breathing with a person, mirroring their breath or taking a breath and inviting them to join you, is another powerful connecting tool.

- Touch. As powerful as touch can be, it can also really turn people off. There must be lots of listening, variations, and responsiveness for it to have the most impact. A firm touch that goes into our muscles and our bones can feel quite grounding, so a squeeze of the hand or a hand on the shoulder can be very reassuring. Sometimes it’s counterintuitive: a gently touch, like a breeze or blade of grass, can also be useful.

How To Use These Tools In Experiential Work

There are many ways that we could adapt these tools depending on the context and experience, but Nielsen-Pincus has defined three useful examples:

- Choreographing a space for a somatic response from the audience. Leaving a moment where you’re going to pay attention to the audience and listen to their reaction – maybe they take a breath, maybe it’s a moment where you see their pupils dilate – is very simple, but can be very profound.

- Step by step progression of somatic steps towards an experience. We might use a combination of the six tools above to build towards a bigger ask of participation from the audience. Think backwards from where you’re trying to go, and what the steps to get there are. Along that road, there might be jumping-off points at any moment.

- Creating tension and conflicting expectation. When we think about breathing or touch, it can feel more attuned to calming and settling down. But the same tools can also be played with to create tension and embody conflict, creating the right level of overwhelm or pull the audience in the right direction.

The Cloak Of Experience: Why Embodiment Matters

When something is physical and perceptible in our bodies, it takes us through a different pathway in our nervous system than we go through when we’re just observing something. These shifts in our autonomic nervous system change the way that we process all the sensory information that we’re receiving.

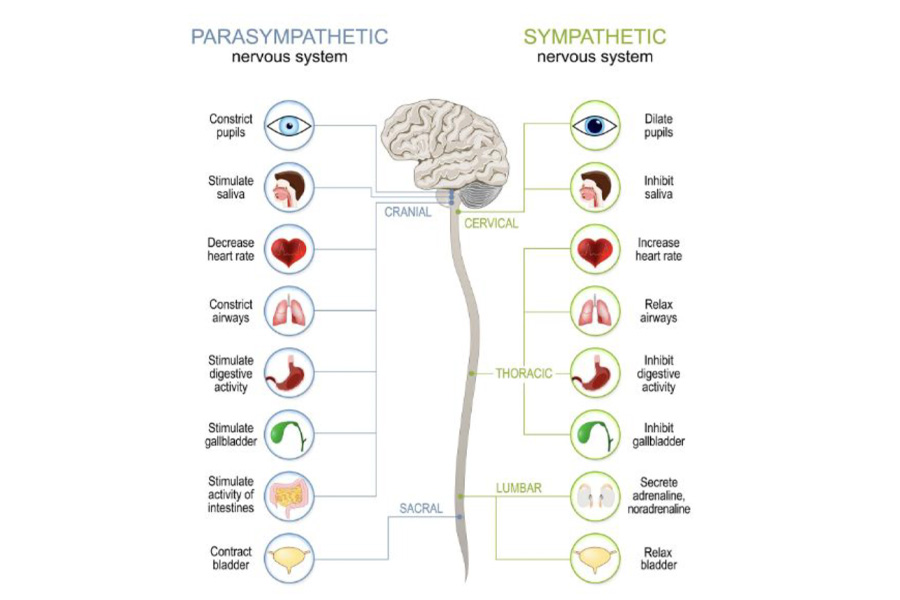

The autonomic nervous system has two sides that are always toggling to find balance:

- The parasympathetic nervous system takes us more towards a focus on rest, digestion, calming, relaxation and inward focus. Our heart rate decreases, our breath quietens, our digestion is stimulated, we take in less light through our eyes, and the blood flow goes to our organs.

- The sympathetic nervous system is more about active attention and presence, social engagement, and an outward focus. At its most extreme it can trigger flight or freeze, dilate our pupils, inhibit our digestion, increase our heart rate, take in more breath, and blood flows to our muscles so that we can move and engage.

In performance, it’s exciting to play between these two sides. We probably don’t want to send people into a fight, flight or freeze, situation, but by listening, adapting and knowing what we want to do with people, there’s a lot of opportunity to play safely with these extremes.

Looking at the limbic system within the brain, this is where we process sensory information and regulate our nervous system. It regulates emotions, especially those related to fear and pleasure, like attraction, nurture, danger and memory. When we start to stimulate these subconscious places, connections start to be made.

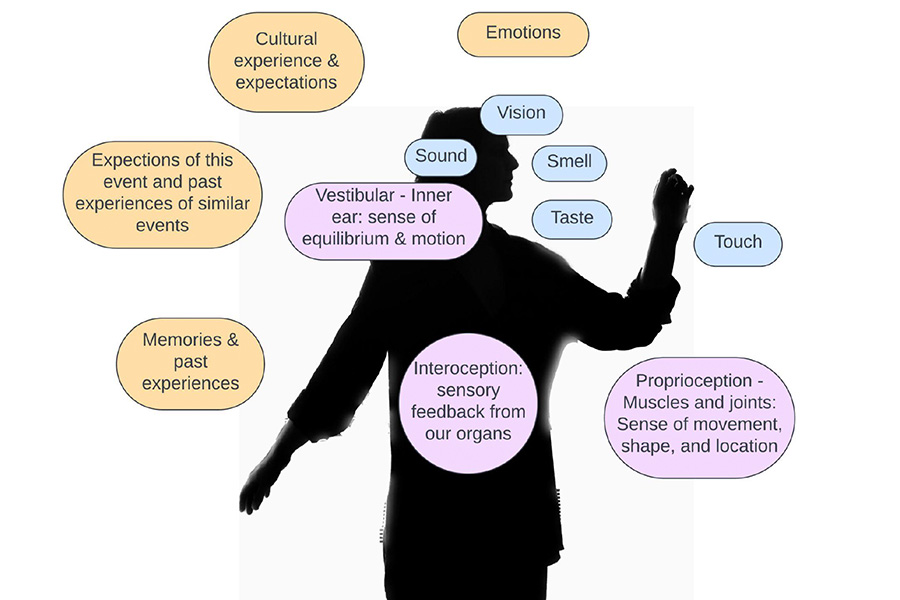

In an immersive situation, all of our senses are involved – not just sound, vision, smell and taste, but also our sense of equilibrium, our proprioception, how our body is moving through space, and our interoception. On top of this lies what Third Rail talk about as “the cloak of experience”: everything personal that a person brings with them that helps them make sense of what’s happening, from their emotions to their memories and past experiences, their cultural experience and expectations, and the expectations they have of this event and similar experiences they’ve had in the past.

“Embodiment and the physical helps us get to this place where our sensory experience meets our emotions, memories, expectations and the regulation of our nervous system, and intertwines with the narratives, themes and concepts of the experience we’re having. It’s where it starts to feel like ‘this is just for me’. And to me, that’s where I find the magic in this work.”

Marissa Nielsen-Pincus

The WXO Take-Out

The mind-body connection and how experience designers might play with neuroscience, hormones and sensory stimuli to direct the way an audience feels their experience is a topic that we’ve noticed coming up time and again in our Campfires, from Michael Badelt’s playing of “the hormone piano” to Kinda Studios’ pioneering work in neuroaesthetics and the ideas explored in Your Brain On Art.

As more and more experience designers start to merge neuroscience with performance and experiment with the results, we’re excited to see what new possibilities to connect with, move and transform people might arise.

So next time you’re designing an experience, ask yourself:

- Which of the six tools might you be able to use?

- What opportunity is there to read and connect with your audience?

- Which side of the nervous system are you looking to trigger?

Want to come to live Campfires and join fellow expert experience creators from 39+ different countries as we lead the Experience Revolution forward? Find out more here.