Sophie Shaw is the founder of narrative design studio House of Cultural Curiosity (HoCC). Her work involves curation, interpretation, visitor experience, learning and education, participation, co-creation, and community arts projects. HoCC is a vehicle for exploring how to tie these different ways of working into a bespoke creative practice, engaging audiences with ideas in powerful ways.

She is also the instigator of The Experience Shift, an open-source research project into the future of immersive experiences in light of the upheaval brought by Covid-19. Here she responds to the “crack of doubt” concept introduced by Joe Macleod in Campfires 33 & 34: The Ultimate Introduction To Endineering, wondering what it might mean when applied to the museum experience.

The crack of doubt. That moment when it occurs to you that this might not last forever. And one of the concepts Joe Macleod introduced as part of Campfires 33 & 34: The Ultimate Introduction To Endineering.

We might experience the crack of doubt in love, in friendship, and in our interactions with products, services and, yes, experiences.

Macleod draws attention to the fact that, while a great deal of human intelligence goes into the start of our relationships with specific aspects of the designed world, very little goes into their endings. He traces this state of affairs back to our cultural reluctance to address endings at all, centred in the fundamental human unwillingness to face the prospect of our own death.

The consequences are dire – this imbalance is one of the factors that has led us to the brink of climate catastrophe. How can we expect regeneration when we don’t make space for things to die? (There is much more to it of course – I refer you to Macleod’s own words).

The Crack Of Doubt In Museums

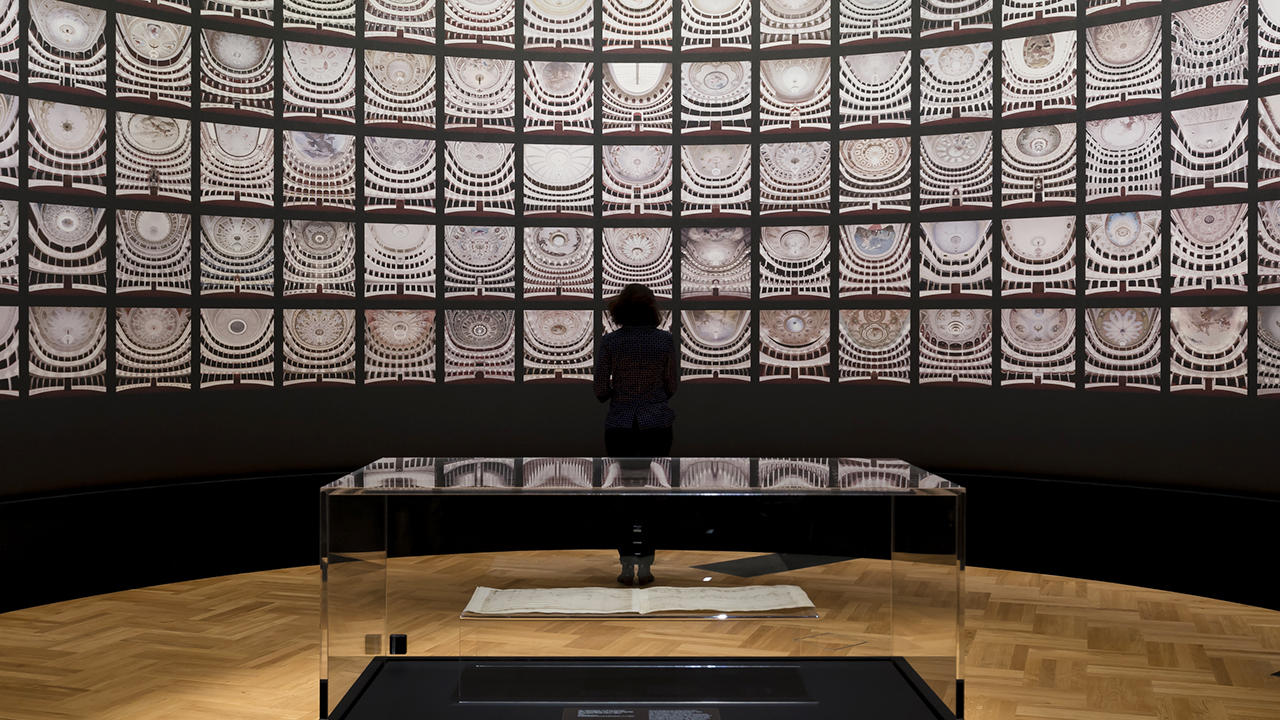

Macleod walked us through a series of exercises – tools created to help designers address the full lifecycle of their product or service, and plan for a good, meaningful ending. With my museum hat on, I was interested in what this might mean for the internal experience of our audiences.

Now, as storytellers we think about endings – of course. When our stories become multilinear and the experiences we build are open-world and free-flowing, this becomes less straightforward.

As designers we have aspirations for dwell times (to expand time spent in an experience) and constraints around footfall (which limit that time), but introducing ‘the crack of doubt’ felt like a good tool to bring what the individual audience member might think, feel and need into the centre of the conversation.

Have you had a museum experience where the crack of doubt starts with aching feet, restless children, an urgent need for caffeine? How might we think about what could constitute a “good death” for a museum experience? What would you say is the ideal crack of doubt moment?

I’ve experienced some terrible crack of doubt moments in a museum context. From “there is nothing for me here but I still have to navigate a confusing maze of content to leave”, to “I’m so curious to find out more but I’m losing the will to live trying to work out what’s going on”, or “that was all well and good but now I’m tired and I need to traverse a large building three times to leave this section, get my coat and bag and find an exit”.

As designers we often put all our eggs into the basket of the audience seeing the experience through to an ending we want for them – we don’t want them to break up with the experience before we’re ready for them to – but in reality it’s really up to them when they’re done.

Thinking in this way pushes me to leave space for the endings to be on the audience members’ own terms. This could impact how I might approach producing content. A guiding principle for me is, “what work can I do so the audience doesn’t have to do it themselves – so they can access the interesting stuff fast, and together we can make sure whatever bandwidth they have is used in the most efficient way possible?”

Introducing the crack of doubt, I might also now ask, “if they drop off here, what are they left with – and is it satisfying?” In terms of storytelling, this is an exciting invitation to stretch my notion of complex, multi-linear narrative structure and to play with balancing the energy that comes from the unanswered question and the satisfaction that comes with making sense of things.

Releasing Visitors With Care

It also pushes me to think about what the visitor needs once they decide it’s over. How do we release them with care and without drawing out the process? There is a big flag here to remember the importance of signposting exits (albeit clearly for those looking, subtly for people who aren’t), but I want to linger on the notion of care.

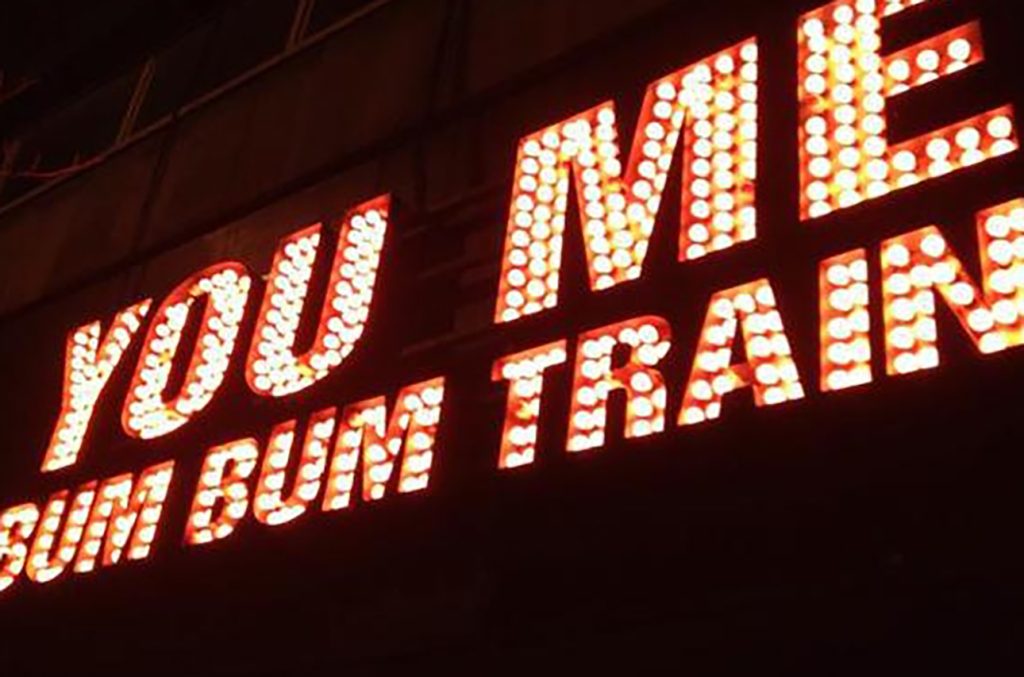

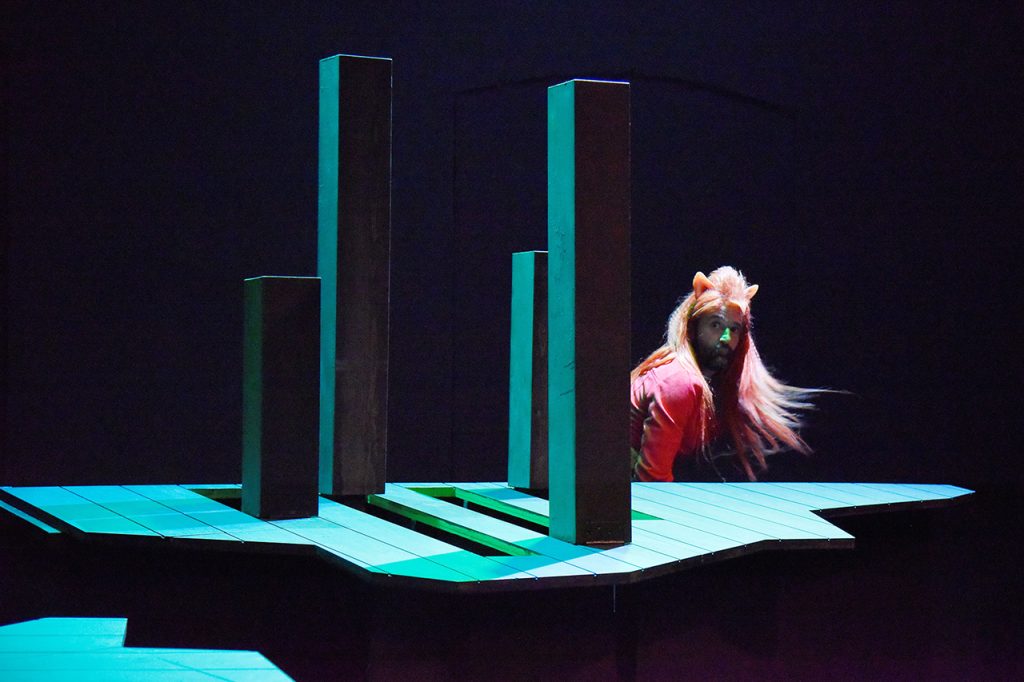

One of the most interesting endings of a cultural experience I’ve been involved with came out of volunteering for You Me Bum Bum Train in 2015. You Me Bum Bum Train, based in the UK, puts on shows where audience members would, one by one, traverse a series of scenarios which put them, with no warning or preparation, into a starring role. Audience members would go from conducting an orchestra to being interviewed by imigration officers, and on and on for around 45 minutes.

Out of sheer curiosity I took part in one performance where (by chance) it was my job to ‘catch’ audience members at the end of their experience, to hear anything they needed to say and make sure they knew where to go next (i.e. cloak room & bar). They had all had a particularly extreme experience, albeit in different ways, and the value of having someone there for them at the end was visceral.

I’ll be honest – feedback walls in museums feel unsatisfying to me. Is this because I need a more immediate sense that my responses have been received by someone? Are there other ways we can think of rounding off a museum experience?

It would be great to hear from the WXO community about what you think an ideal crack of doubt moment might be for a museum experience – and how holding that in mind could impact the way we design these experiences.

Endings And Sustainability

Creating better endings for museum-goers isn’t going to save the planet but there is an urgent need in the museum sector, and in the cultural sector as a whole, to tackle our unsustainable practices head on and re-balance our relationship to resources.

The work to do so will take a shared commitment and a collaborative approach across the sector – my instincts and those of colleagues I speak to (shout out to Curious Space) are that putting more budget into human resources at early stages of projects is key, so there’s time and space for the good thinking about materials and transport, and space to challenge a project’s ambitions and aims.

If a project can’t be delivered sustainably, should we be doing it in this day and age? Is there another way to achieve what we need to achieve? In my experience, good intentions are often explicitly stated at the beginning of projects, but these concerns get squeezed out of the design process because other pressures, which feel more immediate, shout louder.

Would this be different if we operated in a culture which was more comfortable about talking about endings in the round? Can setting a cultural precedence around endings in our relationship with our visitors and audiences be part of making this shift, through concepts like the ‘crack of doubt’ and the other phases of the end Macleod identifies. While acknowledging and adjusting our broader cultural habits won’t fix things in isolation, it does feel like they are related. The more we can address our practices holistically, the more seamlessly we can start to adopt new ways of working across the board.

To get more insights from experts in the Experience Economy like Shaw – and to be the first to know about our membership programme, events and more – apply to join The WXO now.