WXO Case Studies tell the story of how experts across the Experience Economy have faced challenges, solved problems, and either pioneered new ideas or just figured out how to make something work really well.

We believe these experience-based ideas are highly transferable, and that you should be able to take what they discovered in their sector, and apply it in your area of the Experience Economy. If you’d like to share your own case study with the WXO community, please get in touch.

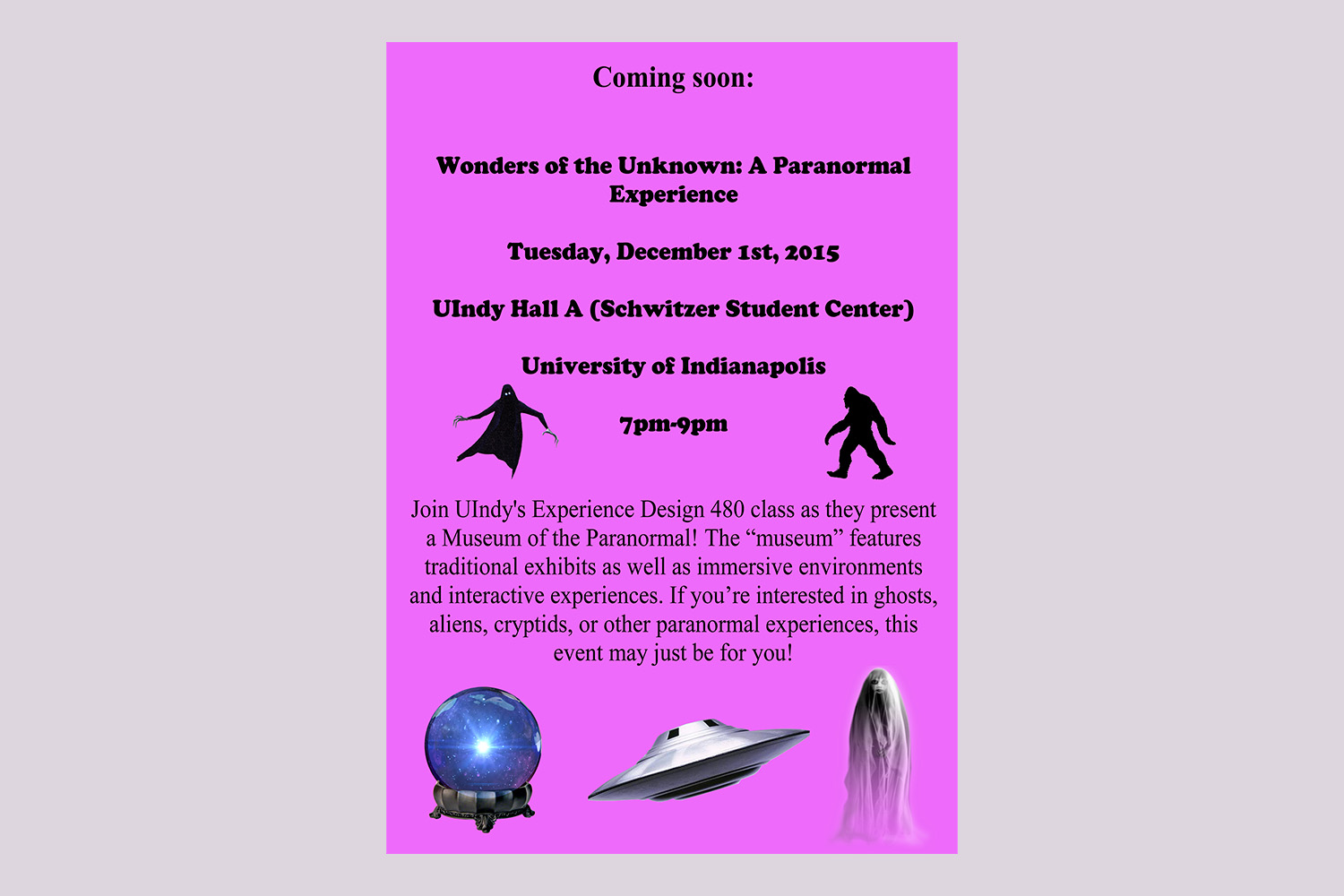

Wonders of the Unknown: A Paranormal Experience was a pop-up event put on by the experience design department of the University of Indianapolis in 2015. The idea behind the experience was to create an interactive pseudo-museum environment that presented stories of the paranormal from the points of view of both the believer and the non-believer. This case study focuses on the immersive ‘Bigfoot Encounter’ microexperience that took place in a handmade sensory booth.

Austin Baker, an associate of the Experience Design department at the University of Indianapolis, tells us:

- How he turned the idea for an immersive Bigfoot encounter into a spine-tingling reality with the help of a sensory deprivation booth, a faux bush, and a spice that smelt like rotting onions.

- Used the pop-up experience as an opportunity to muddy the waters between believers in the paranormal and non-believers, and to get them to see the ‘other side’ in a more empathetic light.

- Created a realistic immersive experience simulating an encounter with Bigfoot on a $300 budget.

- Overcame various challenges to deliver an experience that incorporated four of the five senses and a variety of special effects in a unique, one-of-a-kind spectacle.

Who’s our Hero?

We believe stories Start With Who – so who’s the hero of this one?

The overall macroexperience was done by an upper-level Experience Design course at the University of Indianapolis taught by Dr. Samantha Meigs. As a team, we decided that the main problem with most paranormal exhibits is that they don’t leave much room for nuance; they’re either aimed at those who already believe or those who want to explain away the paranormal with scientific concepts.

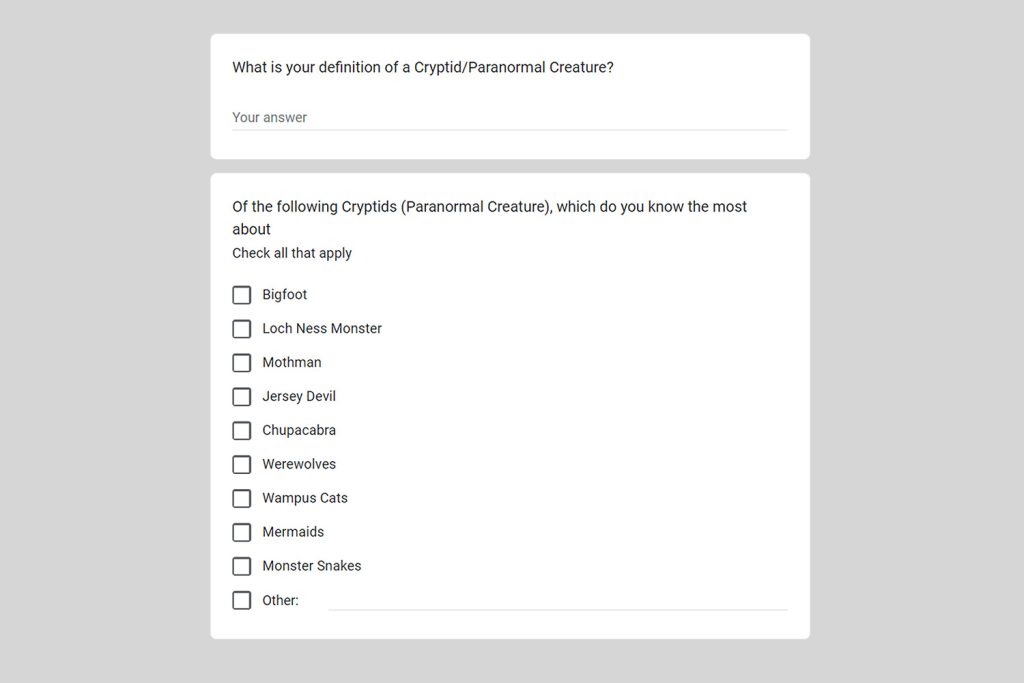

We used this pop-up experience as an opportunity to muddy the waters between the two demographics and get them to see the ‘other side’ in a more empathetic light. My particular microexperience was housed in the Cryptid section of the event, where I worked with experience design students Zoey Freese and Victoria Howell. Our goals were to create:

• A sensory deprivation booth that will randomize between encounters with normal animals and mythical ones. The booth will prove to the guests that it’s next to impossible to know what people who experienced a Cryptid encounter actually saw, which either validates their beliefs or leads them to ask more questions.

• An interactive Fun Facts area in which the guest will learn important facts about the major Cryptids, such as where the belief originates from, the first known encounter with the beasts, what people think they are.

• A ‘describe an animal’ interactive activity in which guests will be asked to describe a normal animal. The guests will then compare their description with a description of a Cryptid in an attempt to show them how difficult it is to recreate a visual image through the use of words. Accompanying this section will be information on former Cryptids such as the Giant Panda, Komodo Dragon, and Okapi – all real animals that at one time were thought to be fake.

What was the Call to Adventure?

What was the problem, either “out there” – in society, the industry, the world – or “in here” – the firm, the community?

The biggest problem when it comes to the paranormal is that it’s one of those issues that modern society sees as purely black and white. Those who truly believe they’ve seen something paranormal or believe in the concept overall tend not to be taken seriously by scientists, media outlets, popular culture and anthropologists, while those on the opposite side of the spectrum are often seen as trying to explain away occurrences of the paranormal without even attempting to understand what actually happened. We saw this as an opportunity (albeit a small-reaching one) to make both sides empathize with the other.

Who was your Mentor?

Did the people going on this journey have a mentor – either a real person or a way of thinking?

Dr. Samantha Meigs, who was the instructor of the course and the Chair of UIndy’s Department of Experience Design, acted as a mentor on this project. With her background in both the museum world and theatre, she helped guide our team in creating exhibits and experiences that were backed up by firm anthropological, folkloric and dramaturgical research. Likewise, she played a major role in the design of the sensory booth/Bigfoot Encounter, thanks to her knowledge of fabrication techniques as well as special effects.

Why did you at first refuse the Call?

Why didn’t you action this before?

The sheer mention of the paranormal creates controversy, and any realistic experience that deals with the topic in a serious manner has an uphill battle before it even hits the ideation phase of the Design Thinking Cycle. Even within the class itself there was debate as to how we should approach the content of this experience, with about half the class skewing towards the ‘believer’ side and the other half on the ‘non-believer’ side. It’s a touchy subject that people tend to have strong opinions about, which makes it challenging from a design perspective.

What was the Inciting Incident?

What changed?

We (as a class) decided that this was a challenge that we couldn’t resist tackling. The class that was associated with this event was also a one-off special topics course, and we as a department didn’t think we’d get a chance like this again.

What would have happened if you hadn’t Crossed the Threshold?

…or done what you’d always done before?

The experience would have been very basic and not immersive whatsoever, and the Cryptid section in particular would have been little more than a traditional museum gallery.

What Trials did you face along the way?

Lack of knowledge? Time? Money? Contacts?

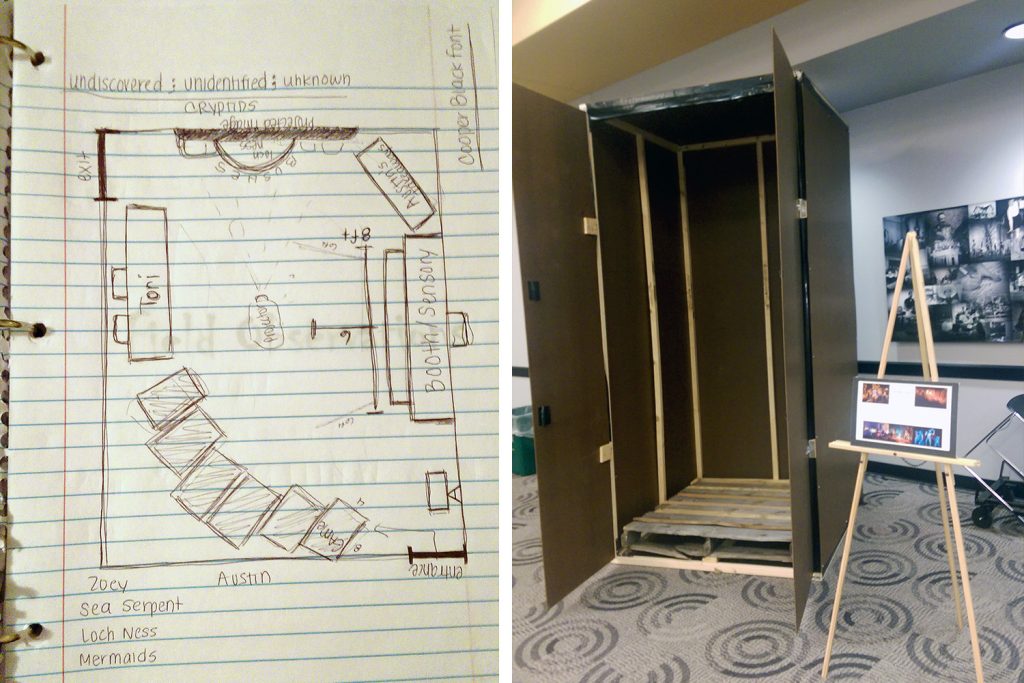

The biggest frustration right out of the gate came when trying to figure out what the sensory booth would be made out of and how it would function. My team, the instructor, and I went through many sketches and prototypes before we settled on a design, which then prompted the next issue: the cost.

The sensory booth ended up being a fairly expensive endeavor that ate up over half of our team’s budget, and this was before we even assembled it. The third issue occurred during set-up on the day of the event, where we discovered that the booth didn’t fit through the doors of our workshop and needed to be wedged into an elevator just to be moved up to the event space!

Being a class housed within a small midwestern University, budget was a huge issue. We only had about $300 total for the entire event, and we estimated that the sensory booth itself would take up about $200 of that if we wanted to do it according to our plan. Likewise, we ran into a couple logistical snags due to the fact we were doing this experience as a pop-up in a rented space, which was only booked for a day. On top of all this, we had to go from conceptualization to implementation in three months!

Who were your Enemies?

There was a constant debate between all parties as to the ethicality of presenting paranormal experiences in a museum-esque setting. My personal enemy during the creation of this experience was the dreaded imposter syndrome.

Building the sensory booth was one of the most technically complicated things I had done in my career up to that point, as it needed to be a holistic multisensory experience that not only transported guests into another world, but also featured a ton of moving parts and effects that had to be operated by a literal ‘man behind the curtain’ in real time. It was all a bit overwhelming, and even while setting up on the day I worried that the whole thing was going to crash and burn.

Who were your Allies?

Who was on your side or helped you achieve your goal?

As clichéd as it may sound, my teammates for the Cryptid section of the experience were my greatest allies. Zoey and Tori were both brilliant experience designers, and the three of us worked like a well-oiled machine as we navigated through the design process. Dr. Meigs was a great ally and resource as well, and without her technical and academic prowess I don’t think the microexperience would have turned out anywhere as good as it did.

What Tools helped you on this journey?

What’s the closest thing you had to King Arthur’s Sword, or Luke Skywalker’s lightsaber?

Strangely enough, our department’s corded power drill acted as my Excalibur in this case! It was the tool that helped me build my sensory booth, and was integral to the creation of several of the special effects that were put inside. There was not a single modification done to the finished sensory booth that didn’t involve the drill in some capacity.

What was your biggest Ordeal?

What was the toughest challenge you faced?

The toughest challenge for this microexperience came not from the construction or conceptualization of the booth itself, but rather the simulation that was to occur inside of it. Those who claim to have encountered Cryptids out in the real world are usually too far away to smell or touch the creatures, which created a design challenge in terms of making the booth a true multisensory experience. The entire microexperience was on a shoestring budget and had to be done with minimal digital technology.

To overcome this challenge, I worked hand in hand with my mentor and my teammates to figure out what sorts of multisensory effects would simulate the first-hand accounts of an encounter. We decided early on that the sensory booth would only work if it was completely in the dark and cut off the guest from the rest of the experience. We built the walls, ceiling and floor of the booth out of dark Masonite, which completely blocked off all external lights.

With our audience deprived their sense of sight, it was easy to manipulate the other senses to our liking. Sound was the simplest, as I used two rounded Bluetooth speakers that were embedded in the walls of the booth. One at the center was used for the various creepy noises (a mixture of both real animals and strange noises such as footsteps in leaves, etc.), while a second speaker was left down at the bottom right corner and constantly played the ambient noise of chirping crickets and croaking frogs.

Touch was a tricky sense to include, though I was able to come up with a solution in the form of a faux bush that was nestled at the back of the booth. It acted as both an aesthetic piece of the design (it covered both speakers) as well as a functional piece.

The bush was tied to a string that was fed through a hole in the back wall, and during the encounter it would shake at random intervals. This almost universally led to a yelp or scream from the guests, as the bush would start to go wild and brush against their bodies unexpectedly! To add to the sensation of the guest walking in a forest, I scattered bits of Styrofoam on the ground to simulate crunching leaves.

As for smell? That one was all Dr. Meigs. To this day I don’t remember what she found, but she brought in a spice that gave off an odor similar to old onions. The second I sniffed it I was repulsed, and decided that would be what we loving referred to the rest of the semester as “Essence of Bigfoot.” To get this to work, I had to wrap up the spice in a small satchel which was nestled in the top corner of the booth and swung past the guest whenever tension was released on its string.

Taste was the one sense that I couldn’t figure out how to incorporate, unfortunately. All of the effects were operated in real time by myself from a curtained-off extension behind the booth. I used fishing line, my cell phone and an MP3 player to achieve the desired effects, and thanks to this method I could make it so no two experiences were the same.

Did you have any ‘Aha!’ moments?

Moments of discovery and inspiration… times when instead of the fog of uncertainty, you suddenly saw the way forward?

The biggest ‘aha’ moment of the experience came when we arrived at the final design of the sensory booth. We had dithered about the different ways it could be built (I remember a prototype that was just curtains and metal pipes), and it became an obsession to figure out how to make this idea tangible while still staying reasonably under budget.

I remember sitting down in our department’s workspace, talking the design over with Dr. Meigs while the rest of the students worked on their own microexperiences around us, and then seeing the cube sketched out in all its glory. Still, we couldn’t figure out how to build the walls, ceiling, and floor; if we used straight-up plywood it would make the booth too heavy to transport, and if we went with curtains or any sort of netting the booth wouldn’t be lightproof.

I pulled up one of our local hardware stores on my laptop, began to search through the different types of materials they had, and had an epiphany when I saw the Masonite. For anyone who isn’t familiar with the material, I like to refer to it as one step above cardboard.

It’s extremely lightweight and thin, though it’s solid enough to keep out light and acts as a sturdy barrier when properly installed to uprights. Perhaps best of all it was affordable! Once I shared this information with the rest of the team and we started to discuss fabrication, the project suddenly felt like it had gone from some pie-in-the-sky idea to something that could be made into reality.

What was the Reward?

What were the results of all your hard work?

In terms of both output and outcomes, this microexperience was a smashing success. When all was said and done, I had created exactly what I’d set out to do, which was a multisensory simulation of a Bigfoot encounter in the middle of our event space, completely cut off from the rest of the world. Though there were plenty of changes to the design along the way, I was able to create something that incorporated four of the five senses and a variety of special effects and (most importantly) was a unique, one-of-a-kind spectacle.

Throughout the event there was a line across the room to get into the sensory booth experience, and in our post-event surveying the class discovered that the sensory booth was the most memorable experience that our guests encountered. They praised its creativity as well as its ability to scare the pants off them, and there were even a few that mentioned how ‘real’ it felt. Perhaps most important to this Experience Design student was the fact that the project allowed me to ace the class.

How does the New World look now?

Now you’ve faced this challenge, what does it mean for you, your organization, and the world?

This was a huge turning point for me as an experience designer. Before this event I had dabbled in fabrication with tools, hardware and construction materials, though I had only ever built small props. Most of my contributions to events came through the ideation phase and via digital channels (posters, information panels, video editing, etc.). This was the first time that I ever attempted to build something so complex in the physical world, especially something that would be seen by the general public and needed to function for several hours.

The success of the endeavor boosted my confidence in my own abilities, and I have since gone on to build much larger and more complex set pieces. For the Experience Design Department, this event is still looked upon as one of our most successful in terms of attendance, audience engagement, and guest satisfaction. We have certainly done more complex and layered events in the years since, though this is one of the classic experiences that the department uses as a standard of measurement for its students.

What might the next Journey be?

Thinking ahead, what might the challenges ahead look like?

We still have most of the props, set pieces and information panels that were used in Wonders of the Unknown, though the sensory booth met a gristly demise at the hands of Indiana weather. However, I believe that it would be very difficult to recreate the same atmosphere, aesthetic, and energy that we had for this experience, mainly due to the fact that it would be a new team and we would have to completely rebuild the sensory booth from scratch.

I fear that such a polarizing topic will have only become even more polarizing in the years since Wonders of the Unknown, and I’d worry that such an event would be met with scrutiny today.

For more case studies and learning frameworks from the Experience Economy, check our Case Studies page here.