“The disability market is the largest untapped market in the world.”

Beth Rypkema

So says Beth Rypkema: accessible arts expert, art guide for Meow Wolf’s Convergence Station, and this Campfire’s Firestarter.

She estimates that this market has over $21bn of discretionary income annually in the US alone – more than the African American and Hispanic populations combined.

So it’s time to ask yourself: why is accessibility often the last thing that immersive experience creators think of?

Rypkema specialises in making art experiences accessible to the visually impaired and those with other disabilities. Her work to create an accessible tour of Meow Wolf’s latest experience, Highlights of the Convergence, was a groundbreaking project in the immersive arts.

As well as making good commercial sense and helping Meow Wolf to fulfil their commitments as a BCorp, it opened up new worlds to the accessibility community – many of whom had thought they would never be able to experience something like this.

Rypkema joined our Campfire to share her vision for “accessibility first”: how by designing to accommodate disability, you can enhance the experience for everyone.

After all, as Arthur Zards commented in Campfire 55: Passion Projects:

“Accessibility isn’t a constraint. It’s an opportunity.”

Arthur Zards

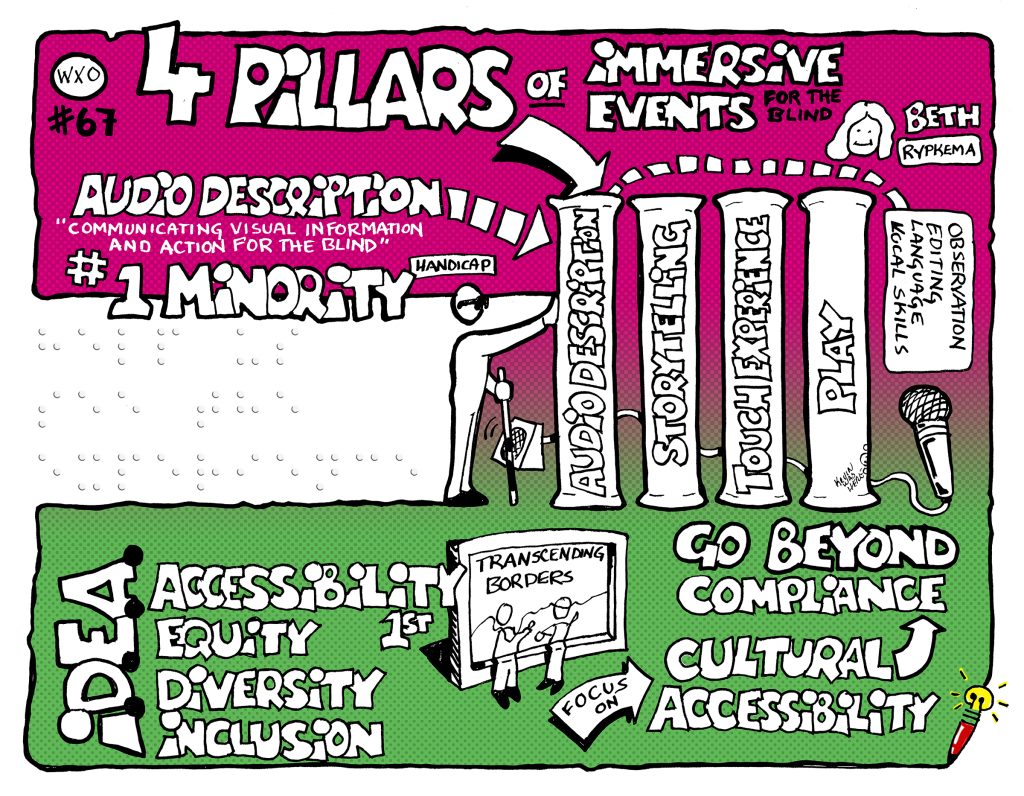

What Is Cultural Accessibility?

In short, it means bringing access to the culture sector, and can take many forms.

It could be recreating famous paintings with textures so a visually impaired person can go on a “touch exploration” tour. It could be hybrid dance teams, creating accessible trails for mountain climbers, or even producing rodeos suitable for cowboys with disabilities.

It could also be championing new forms of creativity, such as ASL slam poetry – a visual poetry based on rhythm and 3D space that enables people from the deaf community to socialise, interact and express themselves.

(For more examples of cultural accessibility put together by Rypkema, check out this list.)

Before the pandemic, cultural accessibility was becoming a big idea among organizations who want to follow IDEA (Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, Accessibility) protocols. It’s also built into the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 and the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

Cultural accessibility generally follows two trajectories:

- Built environment

- Social construct

While society has made huge strides in the former in recent decades, unfortunately the latter hasn’t seen as significant changes.

What Are The Implications For Business?

If you – or your clients – are struggling to see the value of accessibility, Rypkema has some juicy stats that might persuade you otherwise.

- Over 1bn adults in the world are disabled, making it the world’s largest minority group.

- In the US, 1 in 4 adults have some sort of disability.

- World’s largest untapped segment and the third-largest in the US.

- The accessibility community has over $21bn discretionary income annually in the US – more than the African American and Hispanic populations combined.

Moreover, this isn’t a solitary market – those with disabilities will often be accompanied by friends, family, caregivers, drivers, audio describers, guides, and so on.

In short: most businesses are not taking advantage of the nearly half a trillion dollars in market value of this population

Why You Should Put Accessibility First When Designing Experiences

According to Rypkema, there are several benefits to designing experiences with an accessibility first mindset.

- It gives you breathing space and means that you don’t have to panic and make changes later down the line when your build is complete, your budget is gone, and you don’t necessarily have buy-in from other stakeholders.

- You can be more creative with your design flows.

- You can create more cohesive designs, programming and interactive experiences.

- It creates positive brand recognition for you, your company and your clients.

- It expands the experience for the general population. When people look at a painting in a gallery, they look for an average of 10 to 18 seconds. Designing to engage more of the senses can expand the experience not only for the accessibility community, but for everyone else, too.

Audio Description At Meow Wolf And Beyond

Audio Description (AD) is a means of communicating visual information and action for blind and low vision people, or those who wouldn’t otherwise be able to participate. It is used in theatre, film and TV, events, immersive experiences and museums, where it is often referred to as verbal description (VD).

Rypkema advises that you consider these rules when creating an audio description for your experience:

- Describe objectively, not subjectively. Just like anyone else is free to have their own subjective experience, you shouldn’t layer your subjective experience over what you’re describing.

- Describe essentials, as you won’t have time to describe everything.

- Use present tense.

- Match your description to the type of piece. The language and feeling for describing a rodeo is very different to that you would use when describing Shakespeare.

- Don’t explain – let them make their own assumptions.

- Don’t inject interpretation or opinion or censor.

- Limit the use of adverbs.

Rypkema applied these rules at Meow Wolf when developing the AD tour Highlights of the Convergence, managing to turn even the most maximalist visual experience into something accessible.

When it comes to the pacing for a live event like an opera or ballet, this can be very challenging, but not impossible.

“Don’t run over the audio with audio description. Look for brief moments between song and dialogue and do the best you can. I also have a broad pre-show, starting about 15 minutes beforehand, where I talk about things I won’t have time for. Then I do it again at the intermission.”

Beth Rypkema

The Four Pillars of Description in Immersive Experiences

Rypkema has boiled her learnings down to four main pillars when creating well-rounded immersive experiences for people without sight:

- Audio description

- Storytelling

- Touch exploration

- Play

Above all, you should always involve the accessibility community from the beginning. As the saying goes, “Nothing about us without us”.

“You might come up with an idea you think is groundbreaking or fabulous, but if you haven’t talked it over without them, you don’t really know what it will be like.”

Beth Rypkema

Perhaps we should start not only with accessibility first, but with agency and empowerment first, including “design disclosures” that allow people to decide if our experience is right for them.

“I have to caution against making decisions for other people. For example, the rise of online escape rooms during the pandemic was great for opening up accessibility for those who cannot leave their homes. However, I found many of them were a real info dump, which I don’t process that well.

I wonder if we should start including design disclosures alongside trigger warnings. This not only empowers audiences, but is a benefit for creators who don’t want people to attend if they’re not going to have a good time.”

Laura Hess

Intersectionality In Accessibility

Putting accessibility first can feel overwhelming as there are a lot of intersections within the disability community – blind and hard of hearing, lack of mobility, neurodiversity, and so on.

“There’s a misconception that an experience has to be accessible in every way, or we shouldn’t even try. How do we start thinking about making experiences more accessible without thinking that we have to do everything for everybody?”

Laura Hess

Rather than thinking about what you can’t do, think of what you can do and start from there.

“The first thing is to just say yes instead of no. Then, be strategic. Don’t eat the entire whale in one bite. Look at the short, medium and long term. Over a period of time Meow Wolf set up their own protocols for long-range accessibility programming. Just start somewhere! And you’ll reap the benefits.”

Beth Rypkema

Invisible Inclusivity

A truly accessibility-first mindset doesn’t necessarily mean designing a separate experience for those with disabilities. Instead, it means making sure that whoever enters your experience can navigate their way through it intuitively – what Julian Rad calls “invisible inclusivity”.

“When I create tech experiences for companies like Google, I start with my primary audience and think about their journey. Then I ask: how do I enhance it?

Julian Rad

I hate having a section for people who are visually impaired or have hearing problems. No matter who you are, you should be able to come into my experience, navigate it the way you do, and find it as intuitive as it is for anyone with five senses.”

A Museum You Can Listen To

In Campfire 10: How To Create Experiences Using Place, Action And Emotion, we learned how Kevin Dulle’s “ERY Method” can help spark creativity by replacing the obvious verb with something less predictable (a coffee shop becomes a roastery, for example).

What if we played the same game with the senses? Mike Gunawan suggests that by changing the verb of how we’d typically experience something, we can not only make it more accessible to those with impairments, but also enhance the experience for everyone. Take a museum, for example.

“A museum is a visual feast – but if we switch vision for one or more of the other senses, all of a sudden that one experience can have different orientations. Rather than just seeing a museum, what if we could smell, hear or taste it?”

Mike Gunawan

Asynchronous Experiences For All

If you’re designing an audio description experience of an art exhibition for the visually impaired, they don’t necessarily have to be there – instead, you could have a “tour” of the exhibition from anywhere in the road. This doesn’t only open up the experience to the visually impaired, but to people all around the world who are unable to visit in person.

By continually revising this audio description and inviting participants to edit and contribute to it, you could also use the resulting tour as an additional layer for those visiting the museum, planning on visiting the museum, or even wanting to look back on their experience.

“Whatever is being audio described can keep on improving – and the end product will be the contribution of the visitor for the visually impaired.”

Mike Gunawan

Darkness As A Tool

Many events and experiences, particularly in the entertainment sector, are built in places with a small amount of light. Although these experiences will also often use sound effects and mapping to help people navigate, seeing the world through an accessibility-first mindset made multimedia designer Felipe Linares wonder if darkness could be used as a tool for all audiences.

“This session has left me with lots of questions and ideas. Perhaps darkness could be a universal tool that could apply to everyone, and could be a way to start building our experiences differently.”

Felipe Linares

The WXO Take-Out

Designing for accessibility isn’t only the right thing to do: it’s an opportunity.

To make the most of this untapped market, next time you’re designing an experience ask yourself:

- At what point in the experience design process do I usually start thinking about accessibility – if at all?

- How might I adopt multisensory elements to make my experience more accessible and enriching for all?

- How many different ways could I impart the same information or tell the same story?

Want to be part of the most inspiring experience conversations in the world? Apply to become a member of the World Experience Organization here – to come to Campfires, become a better experience designer, and be listed in the WXO Black Book.