The slippery topic of how to measure experiences is one we keep returning to at The WXO – both in the dedicated Campfire 9: Measuring The Value Of Experiences and in discussions we’ve had since, such as Campfire 20’s debate on how we measure immersion.

This isn’t surprising – we might be confident that we’re defining the future world economy, but we still need to convince everyone else along the way. The emergence of a new economic good – experiences – requires a new set of metrics. So how do we go about finding them?

Those who attended Campfire 4: The Difference Between Services And Experiences might remember WXO founder James Wallman’s explanation of the “progression of economic value”:

- We measure commodities, goods, services and experiences differently, using both objective measures – the height of a tree or the distance between A and B, for example – and subjective measures – like the beauty of a sunset, the value of a painting, or how good something makes us feel.

- Tangible goods, i.e. commodities and manufactured goods, can be touched and felt, but we measure and value them differently. Take wheat. As a commodity, we measure its weight. But with a pizza – a manufactured good made of wheat – this wouldn’t make sense. Instead, we look at its size or quality.

- When it comes to intangible goods, i.e. services and experiences, we can’t touch or weigh them. So we have to create a different set of metrics. For a service, this will most likely be through customer satisfaction surveys that cover areas such as efficiency or effectiveness.

- For experiences, it’s a bit less straightforward. Since time well spent is the main currency of the Experience Economy, we can use measures such as time on device (TOD) for apps and technology, or dwell time for IRL experiences.

These are great objective measures – they reflect what’s going on now. But what are the other, subjective measures by which we can judge an experience – and therefore prove the value of the Experience Economy to those who may not yet “get” it?

Proving The Value Of Experiences

This is exactly the problem that strategic experience designer Aga Szóstek faced. With a PhD in Experience Design from Eindhoven University, she consults for companies such as Phillips, Ikea, Google and Santander. Time and again when she visited her clients, they didn’t understand the value of the Experience Economy to their business.

So Szóstek wrote a book, The Umami Strategy, that helps every business to understand how experiences are relevant to them. The Umami Strategy explains how businesses can use “experience thinking” to understand their customers better, stand out from their competitors, create a vision for success, and crucially, measure their progress towards that success.

We asked Szóstek to take our Campfire through her “Umami” process step by step, to see how they might be able to do the same for their own businesses – and circumvent the frustration of having to prove the value of their work and the Experience Economy at large.

How To Be Memorable: Experience vs Expectation

We have two selves within us: the experiencing self and the remembering self.

- The experiencing self is the one that responds to stimuli in the moment.

- But it’s the remembering self – the part of our brain that tries to anticipate an experience based on our past knowledge of the same or similar events – that we need to think of first when designing an experience.

The remembering self is highly connected to our emotions and forms expectations of an experience based on the emotion we’ve experienced in the past – whether that be surprise, fear, annoyance, and so on. So to be memorable, we need to do something that goes beyond expectations and provokes an emotion.

“If something goes beyond the adequate, we get that rush of various hormones and all the emotions connected to them – excitement, surprise and elevation.

So when you create an experience, if you deliver exactly on what you promised, people are not very likely to remember it. If something goes wrong, people will remember and probably avoid you in the future. But if something happens that goes beyond what’s desired, that’s what they will remember.”

Aga Szóstek

Seen this way, it’s no use just being good. You can hear this in “exceed expectations”. You have to stand out.

The Problem Of Positive Adaptation

However, there’s another challenge here. If you use customer expectations as one of your metrics, it becomes what Szóstek calls a trap.

“Of course it’s a trap, because it leads to the syndrome of averaging out.”

Aga Szóstek

As products become better to meet expectations, those expectations rise even higher. On the one hand, this is a good thing for consumers, as the baseline for a quality product continues to rise.

“This is the phenomenon of positive adaptation, which means that no matter how awesome an experience we get, we are going to eventually get used to it.”

Aga Szóstek

But it also leads to heterogeneity, as everything starts to look the same and it becomes harder for customers to differentiate. By trying to keep up with competitors, you lose what makes you stand out.

In the case of consumer goods, manufacturers have responded by supersizing – think 2 for 1 products, for example, or the huge variety of takeaway food we can order on Deliveroo. But this arms race to win over consumers can have unintended consequences. How much has supersizing contributed to the obesity crisis? Does the time we save by ordering on Deliveroo free us up to do something more meaningful, or does it just make us lazier?

As experience design professor Bob Rossman said in Campfire 5: How To Transform Services Into Experiences:

“Supersizing a service doesn’t transform it into an experience.”

Bob Rossman

If one of the objective measures for an experience is time well spent, we might think we could supersize an experience by doubling its length to increase dwell time. However, there’s a question of quality versus quantity here. As Claus Raasted pointed out in Campfire 4:

“If you can make it just as good in half the time, it’s probably a service; if the question is kind of meaningless, it’s probably an experience.”

Claus Raasted

In other words, a 300-minute football game wouldn’t necessarily be more enjoyable, and might even be more painful! Same goes for holidays – if you’ve got a busy work life, taking too much time away might affect your enjoyment of taking a break.

The Umami Strategy

So how will the arms race in the experience sector be won? Szóstek’s answer is to develop an “umami strategy”.

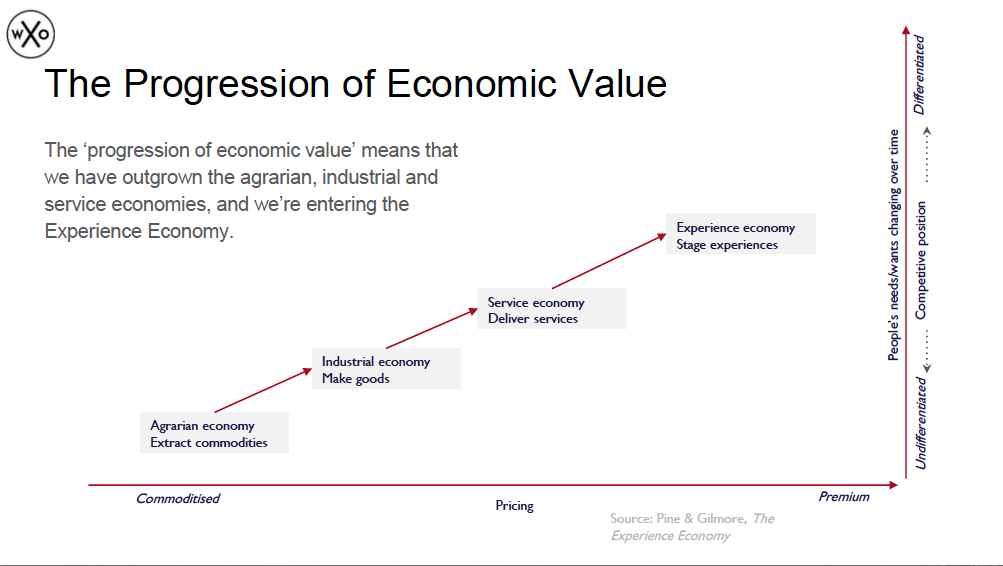

Our taste buds are split into four sections – bitter, salty, sweet and sour. Umami is the spot in the middle of our tongue that unites and elevates all of these.

Szóstek breaks down businesses in the same way – product, employee, customer and business. Too often, she says:

“Companies try to force experience into a process or a department. But actually, experience is everywhere. It’s the umami of your business. And when you think about how it relates to your product, your employees, your customers and your business, suddenly everything gets a little bit more exciting.”

Aga Szóstek

She segments this “umami” into the following:

- Umami baseline: how your customers see you today.

- Umami vision: the direction you want to go in that gives meaning to your business.

- Umami edges: the experiences you create.

- Umami metrics: how you measure your success, which feeds back into your baseline.

To achieve your personal umami strategy, you need to follow four steps.

Step 1: Write A Love Letter From Your Customers

We want to start with our baseline and find out how your customers see you. Szóstek thinks that rather than a survey, the best way to do this is to either ask your customers to write a love (or divorce!) letter to your business, or to put yourself in their shoes and write one to yourself.

“We want to get to this emotional level of how they feel about the experience they went through.”

Aga Szóstek

(If you want to read the longer version of her belief in the value of qualitative data, check out Szóstek’s article on Why Brands Should Ask Their Customers To Break Up With Them here.)

By measuring emotions, we’re measuring expectations – the baseline that we want to build our experience on top of.

Step 2: Figure Out Your Values And Vision

Remember the problem of positive adaptation? That what is exciting and new today will be the norm tomorrow? According to Szóstek:

“Positive adaptation cannot be stopped. But what you can do is slow it down. You do this by bringing meaning to people, so they know that whatever experience they are getting from you, it’s bigger than just having that experience.”

Aga Szóstek

Your business and your customer are the non-negotiables you always have to deliver on. But you can also deliver on a community level, where people are very active, a societal level, where people are more passive, or an environmental level, which can refer to both the space you’re operating in or the planet at large. These five elements are like Russian dolls, with your business the kernel in the centre.

Businesses should ask themselves, where do I bring the most value? And why is this important – both to you, and to the people who come to your business? If you can answer this, you’ll have your “umami manifesto”:

- We believe that…

- This is why we commit ourselves to…

- In order to…

Step 3: Nail Your Differentiators

Once you’ve found your vision, it can be easy to become disconnected from it on a daily basis. So rather than aiming to be the best at everything and becoming overwhelmed, to stay connected to your vision Szóstek suggests picking one or two qualities that you want to be the best in the world at.

“Not a step or two or five ahead of the competition. Like nobody else has crafted in the world. It could be that I’m going to write the coolest emails to my customers. I’m going to have so much empathy that when they call me they are just going to love me.”

Aga Szóstek

When you have your differentiators, it becomes easier to build on them with confidence and take risks, rather than staying on a level of safety. And when you really lean into them, you suddenly find yourself somewhere different, in a place that people want to talk about you.

Step 4: Design Your Metrics

Now that you have your vision and your differentiators, you want your stakeholders to tell more stories that reflect them.

Look at the love letters your customers wrote, think about your vision and differentiators, and imagine what your customer would say. That’s how you get the anchor for your measurement.

“Experiential metrics are those that explain what you would like your customers to say when they talk about you. What you are looking at is whether your vision and differentiators are strong and visible enough that they are actually going to mention them.”

Aga Szóstek

The WXO Take-Out

- You need to go beyond expectations for an experience to be memorable. It must be memorable in order to be successful. So should memorability be a differentiator, as well as a metric, for experiences? In Michael Badelt’s words, his experiences are a “Trojan horse”: they promise fun, but have unexpected ethical and emotional challenges built in so that guests take away something more than they expected, and society perhaps gets a little better in turn.

- What makes people love you is when you tap into their emotional side. Being super efficient, for example, is a pragmatic benefit – but it’s not going to make people love you. They’re probably going to have a very transactional relationship with you. But if you make yourself super efficient and cute at the same time, suddenly you’re getting somewhere.

- As John Connors said, an experience is like Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: the magical moment of transformation is at the pinnacle, but you need the building blocks, such as finances, resources, skills and branding, in place underneath in order to make it happen. This reminds us of the notion of the “hierarchy of experiences” that WXO Founding Members Mat Duerden and Neil Lundberg are working on. And that as a community, we want to define the tools to help build this scaffolding so that we can create better and better experiences.

Interested in taking part in discussions about experiences and the Experience Economy? Apply to become a member of the WXO here – to come to Campfires, become a better experience designer, and be listed in the WXO Black Book.