What if you could read your audience’s minds?

When it comes to measuring the impact of our experiences, we’re often limited to the qualitative data that comes from asking people what they thought.

But this approach has its limitations. Firstly, people lie! And secondly, our conscious answers don’t always reflect our unconscious emotional state.

We believe that having data that tells a compelling story about our experiences is one of the key things that will help people take the Experience Economy seriously – as well as giving us the tools to continuously improve our experiences, making them more relevant, profitable and sustainable. It’s why we’ve hosted previous Campfires on A New Way To Measure ROX, New Metrics For A New Economy, and Measuring The Value Of Experiences.

And it’s why we were thrilled to welcome Leah Ableson: a data analyst, primatologist, and performer and director. She’s worked in the immersive theatre space for nearly a decade, leading audiences through highly intimate experiential performances like Bottom of the Ocean and the ASMR experience Whisperlodge.

Ableson is in a unique position to draw data out of audiences that can be used to build better experiences. As a performer, she’s constantly interfacing and collaborating with audience members, often asking very personal questions or exposing them to vulnerable situations. As a director, she’s well versed in determining how an experience is delivered.

Her background in primatology (she spent three years studying Japanese macaque monkeys!) means she understands how to study behavioural data, and her Media Studies degree that she’s used to questioning why consumers like what they like. Finally, her full-time role working in data technology at Etsy allows her to explore why they do what they do.

She brought this weird and wonderful mix to an inspirational and also practical Campfire explaining how performers can collect field data on audience interaction and leverage it to meet your guests’ needs – without them ever having to ask. We also explored how effective knowledge shares between performers and creative teams can up the efficacy of your playtesting.

So if you’re feeling stuck on audience surveys to extract meaningful data from your audience… read on for revelations that might just flip the way you think about measuring the impact of your experience.

Implied Data = Your Unexpected Gold Mine

“What sets experiential work apart from traditional media is the consumer’s ability to share their own experiences in real time.”

Leah Ableson

Whatever sector of the Experience Economy you hail from or the specific details of the work you do, you can probably agree on one thing: what distinguishes experiences is that the consumer has the ability to decide what level they wish to engage in.

Hidden in that engagement is a total goldmine of data that can tell us what keeps them not only engaged, but coming back for more. But how can we access it?

There are several feedback tools already out there, some – or all – of which you probably already use. These include:

- Playtesting

- Feedback forms

- Review websites

- Sales analytics

- Verbal feedback

However, what about implied data – the information that consumers might not think is helpful to share, or won’t be reflected in these traditional measuring processes?

“Which room in your experience reminded the audience member of their childhood bedroom? How are they subconsciously reacting to being touched? The potential of this data is vast, but also largely underutilised thanks to the gap in how we collect it.”

Leah Ableson

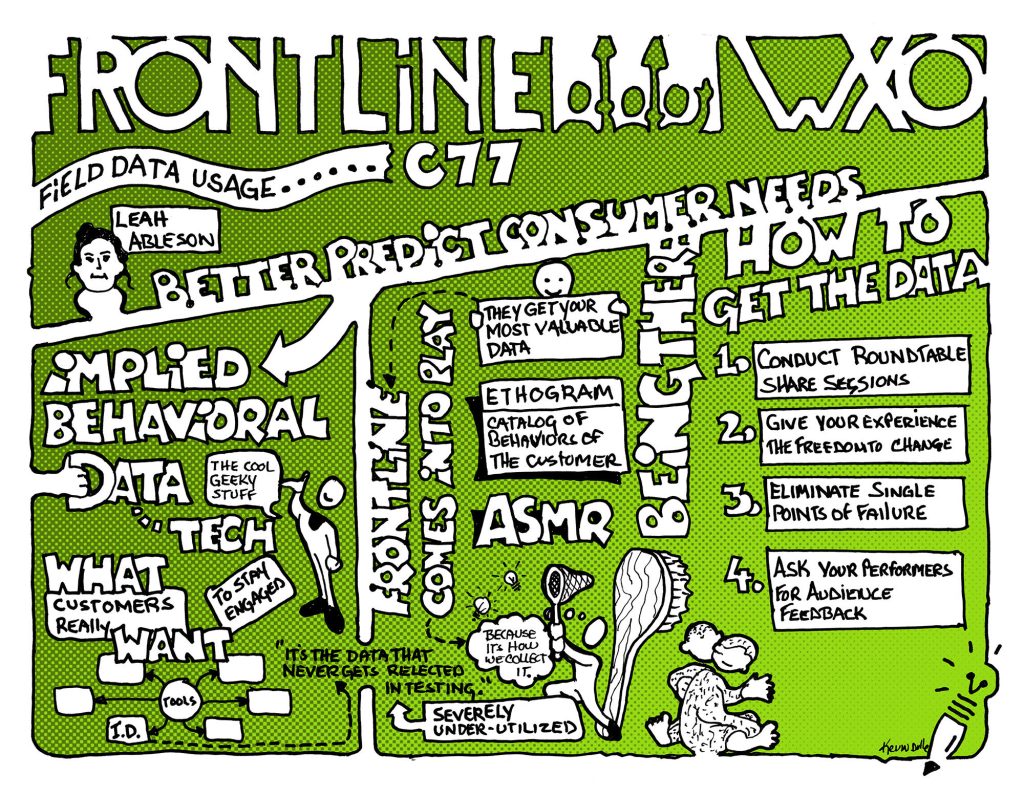

For Ableson, the key to unlocking this data lies in your front line: the people working within your experience who have the highest touch with consumers. For many experiences, this will be actors or performers – but it could also be floor staff, facilitators, customer service agents, and so on. Whoever spends the most time interacting with and observing consumer behaviours will get you the most valuable data. But how?

Why Treating Your Audience Like Monkeys Is A Good Thing

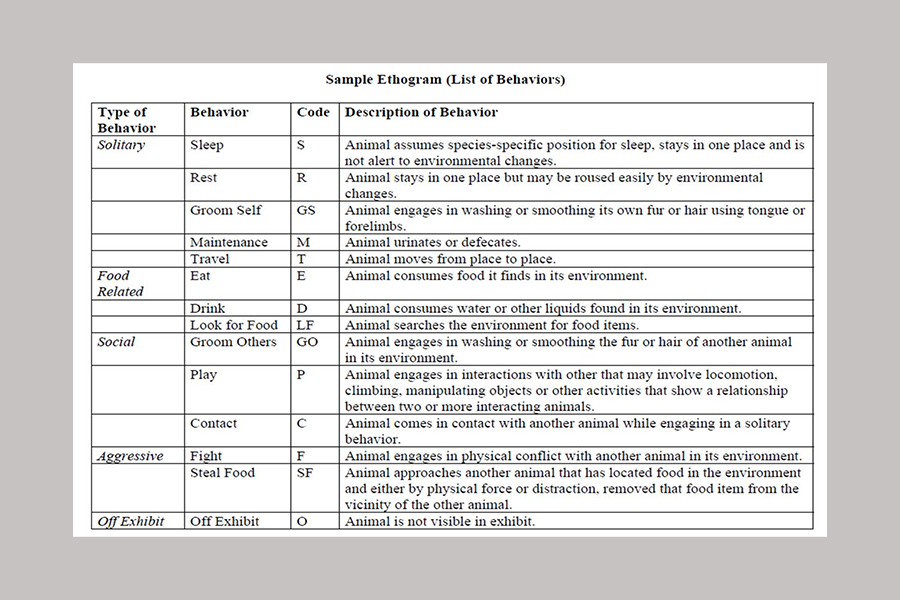

Ableson’s background in primatology means that she spent years studying animal behaviour, specifically that of Japanese macaque monkeys. This introduced her to the tool of the “ethogram”: a monotonous catalogue of animal behaviours noted by subjects by recording everything they do over a long period of time.

On the surface, this data might tell us one story. Take Ableson’s example of watching three monkeys sleeping. The alpha male wakes up and wanders off. The older female goes to groom him. The younger female follows and is struck by the older female, causing her to retreat and start pulling her hair: a classic signal of distress.

We might interpret this as a tale about females competing to serve the alpha male. But from observing the group over months and years, Ableson was able to discern a different story. In fact the monkeys weren’t sleeping, they were lying awake, bored. The fights and hair pulling weren’t about hierarchy, but about having something to do and communicating existential dread.

“This is implied data – and it shows the importance of observing your subjects over a long period of time and without preconceived notions.”

Leah Ableson

And guess what? We can bring the same approach to bear when studying participants within our experiences.

A Thousand Normal Responses Will Help Identify The Outlier

In the ASMR experience Whisperlodge, guests are taken through a series of one-on-one rooms focusing on different aspects of ASMR (despite popular belief, it’s not only about auditory, but other sensory stimulation). Their faces are brushed with make-up brushes, for example, and they receive a pseudo eye exam.

For many audience members, they reported that the room where they had their hair brushed was their favourite. It’s nostalgic, linking to a childhood sense of vulnerability. But what happens if someone with no hair walks into the room?

To avoid this happening, the Whisperlodge team used to reroute the entire show if an audience member with no hair entered – a chaotic, last-minute adjustment that wasn’t ideal for a live performance. But one day, a bald man slipped through the net and ended up in the hair-brushing room with Ableson.

“Over the course of a 12-minute scene, I took a hairbrush to the bare head of the man and down his back and arms. I felt his breath slow and his body relax, before he murmured, ‘I can’t remember the last time somebody touched my head.’”

Leah Ableson

If he’d been asked beforehand, the man would probably have said “I don’t think this experience is for me”. But thanks to this encounter, Ableson realised that she didn’t need to decide which experiences weren’t right for people, but to allow for the possibility for them to engage in a way they weren’t aware of. Some people might need more convincing, but they could be convinced.

In this case, Whisperlodge invested in a head scratcher tool for the same room, which became a universal favourite. The implied data allowed them to predict the needs of their future guests and improve the experience for everyone.

Ableson couldn’t have reached this conclusion by playtesting or asking for feedback.

“When you’re working with living, breathing beings, there will always be changes. We have to decode that language. By continuously observing your audience over a long period of time, your front line is creating the same data as an ethogram. What were the significant events that deviated from the norm?”

Leah Ableson

There’s no other data that can tell you the truth about audiences like this implied data can, including the boring stuff. A thousand normal responses will help you spot the outlier that might transform your experience.

How To Access Implied Data

In the above example, Ableson encountered the implied data almost by chance. But there are several things that you can do to dig it out.

- Conduct regular round tables or share sessions with your front line. Their jobs are constantly evolving based on their interactions, so learning how a performer reacted in real time is a great way of solving a problem before you even knew it existed. Performers also care about what they’re doing and want to talk about it, both to better the audience’s experience and their own working environment. So make sure performers talk – not only to you, but each other – and keep a record of what they say.

- Give your experience the freedom to change. Don’t be precious with your work: allow audiences to make requests through their behaviour. Your work will shine most brightly when it affects someone most deeply, and this may be in a way that is different to what you imagined.

- Work to eliminate single points of failure. You can’t always predict curveballs, but you can look to the evidence for occurrences that might prevent a performer getting back on track. For example, does the rest of your narrative depend on an audience member saying yes? Will a prop failure derail the experience? Is there a different path your performer can take if someone is visibly uncomfortable? Considering these elements will not only protect you from failure, but also open you up to different kinds of feedback.

- Ask performers for audience feedback – as much, if not more than, you ask your audience. Your front line has responded to every permutation of audience feedback, and is also much more unbiased than an audience member.

The Link Between Implied Data & Accessibility

One of the beauties of thinking about implied data is that it also challenges you to question your assumptions to try and make sure that everybody is having an equal experience. Ableson suggests that you put different types of consumers through your experience and dial back if there’s something that they can’t interact with, even if it changes the work from how you thought it would look.

“The real tool is a person’s mind. The truth of any experience is that all we can do is stimulate that person.”

James Wallman

This reminds us of Campfire 67: How Meow Wolf Makes Art Accessible, and the importance of designing for accessibility first.

“One of the issues with the accessibility-first approach is concern about not being able to make your experience completely accessible. This triggers a sense of overwhelm: is my creative vision going to be compromised, or will it induce creative paralysis?

The framing of ‘what are my assumptions?’ makes this process start to feel more concrete. Accessibility is not a checkbox at the end: it makes it better for everyone. It’s a two-part process in challenging assumptions, both within your team by bringing in people from different communities who can add their voice.”

Laura Hess

Implied data is useful in this instance because it allows us to see how somebody responds rather than asking them directly. By having different people in the playtesting phase, we can also pick up this data and evolve our experience over time.

“During the development of Meow Wolf Denver, Beth & Brenda reminded us that we don’t have to do everything all at once. Think about inclusive design over time, and start with the invitation into the development process through playtesting. Feeling invited and welcomed goes a long way.”

Barbara Groth

Putting your performers in the shoes of different audience members can also help them pick up this data. When developing a series of events for the Science Museum, experience designer Pigalle Tavakkoli brought in an accessibility expert who blindfolded all staff and brought them through the experience. This not only engendered empathy, but was a great experience for the staff themselves.”

“The simplest thing was the most eye-opening. You should bring community partners in from the beginning, then train the staff who are going to be delivering the experience.”

Pigalle Tavakkoli

We should also recognise that accessibility goes beyond just navigating the physical space, but navigating an experience emotionally and psychologically too.

“If you give equal credence to all three, I think accessibility has been fairly addressed. But sometimes we put too much in one bucket. Space can be solved by thoughtful spatial design. If you’re working with recognised IP, psychological access doesn’t have to be explored – you can assume everyone knows who Mickey Mouse is and how he behaves. But creating something like Whisperlodge, where you don’t have a point of reference, it’s a different story.”

Tom Vannucci

Can You Teach Emotional Intelligence?

If we’re relying on data drawn from the front line, how can we make sure that they’re interpreting the audience’s reactions correctly? Do we need to put together an emotional intelligence guide, for example?

Perhaps it’s as simple as making them aware of the nuances of human behaviour, and the fact that everyone reacts differently depending on their history, culture and conditioning.

“In Bottom of the Ocean, we ask people for a time they’ve been hurt. We noticed males react differently when sharing their answers, which made it even more important to get it out of them. The end result shouldn’t be different, but the means might be. If the person is a harder nut to crack, the end is more satisfying.

To train someone to be emotionally intelligent, the key is to make sure they’re doing what they want to do –people are never going to be their best if they don’t want to be in the room. If the people on your front line are happy, they’re going to do a better job.”

Leah Ableson

Can Data Collection Be A Distraction?

Getting your front line to collect audience data sounds great – but let’s not forget that they have a main job to do. Could looking out for audience reactions actually be detrimental to that?

“As a performer or facilitator, would I have the time and attention to keep something like an ethogram? To what extent would keeping a record distract me as a performer? And how would my role as a performer make me biased? Do we need an external eye or technology to address this?”

Bernd Gibson

Unlike an ethogram, which records all behaviour at short intervals, with performers this data is collected over a long period of time. When you’re face to face with your audience, you’re likely to be checked in and observant – but this doesn’t mean you have to be constantly monitoring and recording them.

Perhaps a combination of subjective performer data and an objective external eye could yield the best results.

“For long-term installations, we have cameras watching the guest experience as we evolve it. At no time do I want the actor to be outside their circle – they should be present, not observing and taking notes. Always have someone outside observing, and then connect with your creative team after.”

Tom Vannucci

Create A Circle – Then Break The Rules

What about when both your audience and your performers are front end and back end, as in a co-created experience like those run by Barbara Groth, where the audience is invited to become performers, and the performers themselves are also experience designers?

“The starting point should always be that you’re all people in a room – there’s no power play. Allowing humanity into experiences is really important, by releasing control and power on the creative side and allowing yourself to make mistakes. This then allows the audience member to make mistakes. Experiential work is often met with audience members being nervous about not knowing the rules, but that’s a big inhibitor to enjoyment. It’s about setting a circle you can break the rules in.”

Leah Ableson

You need to invite your audience to cross the threshold and enter a state of flow where anything can happen. This might not always be comfortable, but as long as you operate from a place of consent and allow for different pathways through the experience, it can be powerful.

“Often people get overwhelmed or have feelings they don’t expect to come up. You need to build an ability to pause into your time so you can look at them, be with them and be present. How do we extract this person to a safe place until they feel ready to reenter? How do we allow the audience to drive the scene?”

Leah Ableson

This is relevant even if you’re designing for a certain level of discomfort, as in horror attractions. You still need to allow audiences to consent repeatedly and be aware if they might be too scared to express their discomfort verbally.

“Making assumptions about people’s reactions is difficult, because when people are scared they react in unpredictable ways. I’m trying to run a relaxed version of an experience next week – it sounds counterintuitive, but I feel there’s a way to put this on for people who want to feel fear, but a less intense version.”

Sophie Shaw

The WXO Take-Out

We love the idea of using ethograms as the basis for all customer journeys, grounding them in scientific data rather than assumptions. In particular, the idea that it’s only by observing everything over a long period of time – including the boring stuff! – that you can discover the gold that will transform your experience.

The flexibility of Ableson’s approach, which is based on a co-created and collective “test and iterate” model that puts audience feedback above the sacred vision of the designer, also strikes us as a far more sustainable and reliable way of developing an experience that is more accessible, equitable and profitable.

So next time you’re designing an experience, ask yourself:

1. How do conversations between the “front end” and “back end” members of your creative team work now?

2. What ways in the past have you, as an audience member/consumer, provided feedback via your behavior to a performer of an experience?

3. What questions about an experience can an audience member answer that the creator of the experience can’t?

To continue the conversation, WXO Members can head to the topic on My WXO here.

To see the full line-up for the WXO Campfires Season 5, click here.

To apply to join the WXO and attend future Campfires, click here.