Daniel Hettwer is the CEO of Hidden Worlds Entertainment – an immersive experience-based venture run by leaders in the fields of conservation, themed entertainment and technology, creating attractions with a purpose.

Here he explores how the media and entertainment sectors can become better at creating impact and the role the entertainment industry can play in sparking positive changes when it comes to protecting the planet by merging tribes through common interests and motivating them to take action.

- A behavior occurs when motivation, ability and a prompt are present. Everything we do is about escaping discomfort.

- Our brain accounts for 20% of our energy use and operates autopilot to preserve energy. It’s optimized to minimize friction.

- Shocking or fearful content can increase memory, recall and positive behaviour due to the tension it creates.

- One matters more than many: the focus on an individual achieves the necessary emotional connection to motivate action.

- We need to frame peoples’ choices by giving them a small but compelling range of achievable options that provide wins.

- By providing a reward first, the likelihood of an investment is significantly increased.

Why A New Model Is Needed

“Climate change widespread, rapid, and intensifying.” (IPCC)

“Climate change: IPCC report is code red for humanity.” (BBC)

“The U.N.’s Terrifying Climate Report.” (The New Yorker)

Do you feel uneasy reading these recent headlines? How about this: “World’s scientists say disastrous climate change is here” (Politico). Terrifying, disastrous, code red.

Are you surprised? No? Me neither.

We have known for quite some time that this is the direction we are heading in. But are we living in a bubble? Looking around in the developed world, how many people agree with the IPCC report? How many people even know of the IPCC report, or the IPCC for that matter? “Many,” “a lot,” “almost everyone,” you might say, but I’d argue that you have fallen victim to biases here, considering information that is readily available and might not be the most representative.

I can see plenty of examples of people with two degrees of separation from myself that either deny climate change or trivialize it compared to other challenges. Yet, at the same time, these people matter. Their actions will have an impact on the wellbeing of your children, your grandchildren, and all the generations that follow. Looking over at my beautiful baby daughter while writing this, I can’t help but shiver a little.

Clearly, we need large-scale behavior change. But how? How do we create mass awareness and turn this awareness into behavior change? Behavioral science provides fantastic models here.

If you are in the media and entertainment industry, please bear with me a little. Why? Because we have the power to create change. Pre-Covid, the global box office stood at over US$40 billion, and while it is steadily falling, Netflix alone has grown to 200 million subscribers.

Moreover, according to the Themed Entertainment Association, over half a billion people visited major theme parks in 2018. Note the emphasis on major, i.e., this doesn’t yet include emerging formats such as Meow Wolf, a creative powerhouse that attracts over 500,000 visitors to its Santa Fe location and is expanding into major hubs such as Las Vegas and Denver. Also, witness the rise of the Van Gogh Live Experience, a touring format that is visiting all but three of the 35 major metropolitan areas of the United States.

The movie and themed entertainment industry is huge, and provides the benefit of uninterrupted attention for a longer period of time—all within a non-political candy wrap of family-friendly fun. As such, this article is about you becoming the hero that contributes to saving our planet.

Understanding The Science

Let’s start with a quick introduction to Dr. BJ Fogg’s B=MAP model. In a nutshell, a behavior occurs when motivation, ability and a prompt are present. If one of these elements is missing, the behavior will not occur.

Motivation: According to the model, there are three core motivations, namely Sensation, Anticipation, and Belonging. These have two sides each: pleasure/pain, hope/fear, acceptance/rejection.

Ability: Here three paths are highlighted. Train the audience (avoid this if possible), provide tools to ease the behavior, and lastly, scale back the target behavior making it easy. Importantly, the relationship between motivation and ability is compensatory, i.e. when motivation is high, one can get people to do hard things, but only easy things will be achieved when motivation is low.

Prompt: A call to action. While very nuanced, all we need to remember for now is that the trigger must match the audience’s context of motivation and ability.

Note that the model promotes a virtuous cycle. For example, executing an action creates learning, which increases one’s ability and lowers the threshold of future action.

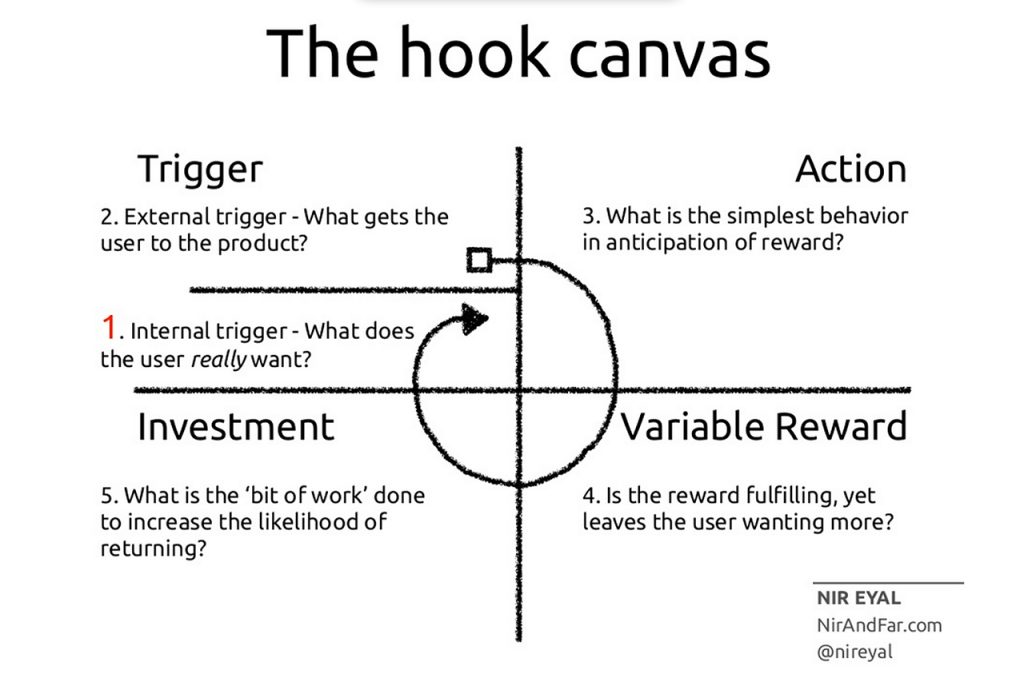

BJ Fogg’s model is brilliant as it provides the foundation for other models. For example, in Hooked, Nir Eyal provides an excellent framework to summarize the habit formation process.

1: Trigger: Prompt the consumer to do something. This trigger should initially be external, bringing the consumer into the habit formation process.

2: Action: Incentivize an action. Promise a reward and show how to achieve this. The action should be simple and delightful.

3: Variable Reward: Something useful or entertaining. The reward needs to be variable to avoid the consumer anticipating the reward and losing interest.

4: Investment: Ask for a personal contribution. A small little trick as we value things we worked on more than they are actually worth. This, in turn, will create an internal trigger creating a virtuous cycle.

Nir Eyal, Hooked

Combining the above with additional insights from behavior science allows us to analyze how the media and entertainment sectors can become better at creating impact.

Our Beautiful (Lazy) Brain

Our brain takes up only 2% of our body weight, but it accounts for 20% of our energy use. As a result, the brain operates on autopilot most of the time to preserve energy. The brain does not like to work, and the brain does not like friction. Most of human irrationality can be explained by this, leading to the below issues.

Getting The Attention

As stated by both BJ Fogg and Nir Eyal, we need a prompt or initial trigger. This should be easy; we all know that “if it bleeds, it leads,” right? There is a psychological cause for this: negativity bias.

In Negativity Bias, Negativity Dominance, and Contagion, Paul Rozin hypothesized that humans give greater weight to negative entities. It is only natural then that we are served headlines that satisfy this need.

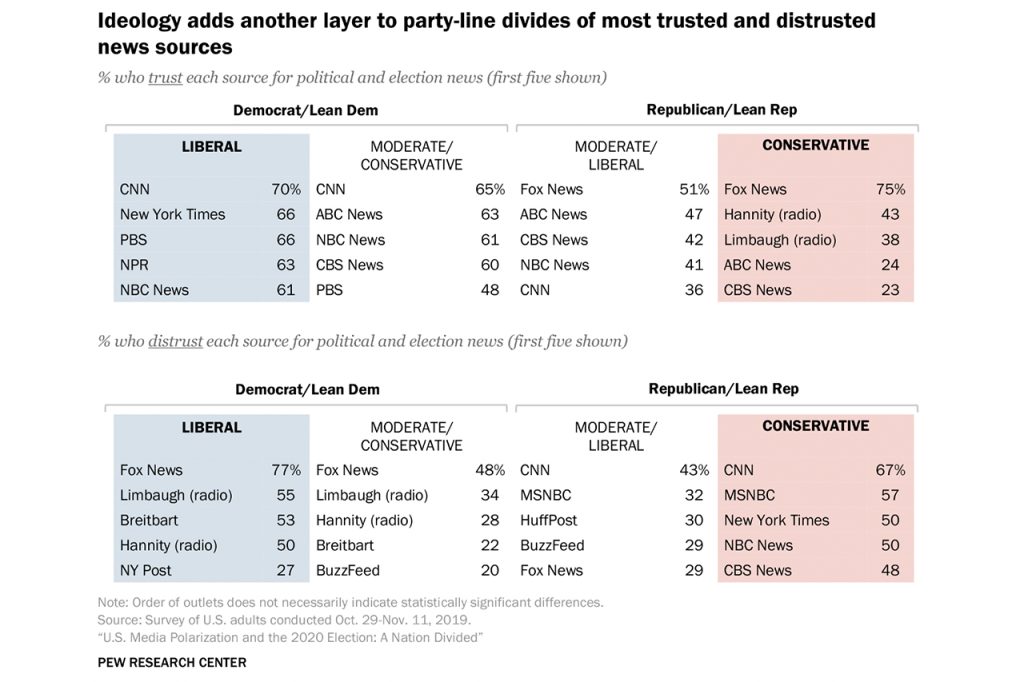

This is, of course, problematic, especially in the context of the news industry, as this negativity bias comes with a heavy dose of sensationalism and political polarization – a very toxic cocktail. In 2014, the Pew Research Center released an interesting study: Political Polarization in the American Public. Here, we see how Republicans and Democrats are more ideologically divided than at any point during the previous two decades.

Moreover, in 2020, Pew released U.S. Media Polarization and the 2020 Election: A Nation Divided, where it showed that each side deeply distrusts the other side’s trusted news sources. But if something is factual, should it not be believed independent of political affiliation?

The Power Of Groups

“The brain is optimized to minimize friction”

Steven Pinker, cognitive psychologist

In Language, Cognition, and Human Nature, Steven Pinker notes that the brain is optimized to minimize friction. Disagreement with your in-group creates friction; ergo, the brain might believe in something that is factually false for the sake of social acceptance.

So, if a group believes in something that is factually false and the group’s view is becoming increasingly skewed on the back of sensationalized media, then reaching each member with facts is going to be increasingly hard.

The underlying concept, ‘Cognitive Dissonance’, is well-studied, and I recommend Leon Festinger and colleagues’ When Prophecy Fails. Here, the authors describe their most famous experiment in beautiful detail: embedding themselves in a cult led by Dorothy Martin, who believed that spacemen would come in flying saucers to save believers from a flood.

Needless to say, no flying saucers or floods arrived, but instead of giving up, the believers doubled down. If we can’t convince cult members that no spacemen will arrive against clear evidence, how can we convince climate change deniers that climate change is real and manmade?

Hope Vs. Fear

Whether a group is willing to believe in facts is one thing, but how these are framed is another. For example, we know that shocking or fearful content can increase memory, recall, and positive behavior, presumably due to the tension it creates.

But is this always the right approach? There is an ongoing debate in the conservation space on whether hope or fear is better at stimulating behavior change. Grist provides a solid overview here.

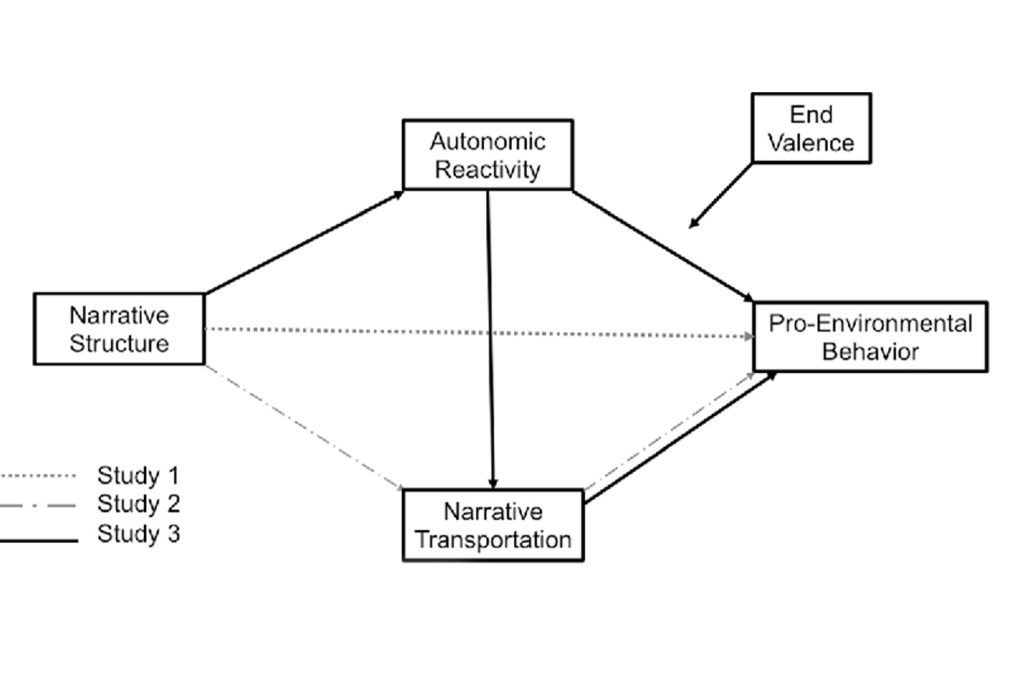

However, looking into our own research, it increasingly appears as if both doom (‘loss aversion’) and hope (‘gain frame’) can work, provided the information is wrapped in a compelling story. Hence, there is increasing evidence that it’s not about the frame itself but our ability to communicate said frame effectively utilizing storytelling.

Facts Vs. Story

Why would a story-driven approach be so powerful? In Psychic Numbing and Genocide, Paul Slovic explains that motivation is driven by complex emotions such as empathy and attention as well as affect.

Affect, in turn, is highly influenced by images, visual or otherwise, to which positive and negative feelings become attached. As such, one of the most effective ways to generate motivation is storytelling, an art form combining all these drivers. Let’s be honest, most of us prefer reading a captivating thriller over a factual publication.

I love Dr. Paul Zak’s article How Stories Change The Brain (full disclosure Dr. Paul Zak, Dr. Jorge Barazza, as well as the amazing team at Immersion Neuroscience, who are Hidden Worlds Entertainment affiliates). He investigated narrative arcs and their neurological impact and found that these have a major impact on empathy and decision-making.

A structured narrative, through its peaks and valleys, creates an interplay of tension and release, generating the emotional buy-in that ultimately drives action. But stories themselves can be optimized further.

One Matters More Than Many

“If I look at the mass, I will never act. If I look at the one, I will.”

Mother Teresa

The aforementioned research by Paul Slovic and others has shown how statistics of mass murder or genocide, no matter how large the number, fail to spark the correct emotional response. The focus on an individual, however, achieves the necessary emotional connection and motivates action.

For example, what would you say is the first thing you recall when thinking about Afghanistan? The invasion 20 years ago? The nearly 111,000 civilians who have been killed or injured? My guess is the majority of us would mention the image of a baby being passed over a wall into the safe hands of a US marine.

Who doesn’t get a weird feeling seeing this and thinking of their loved ones? Or perhaps the image posted by Major Sergeant Nicole Gee, holding a baby in her arms, stating that she loves her job, days before falling victim to a terrorist attack? Statistics versus stories.

The Syrian Refugee Crisis is another perfect case study. When toddler Alan Kurdi died in September 2015, a cumulative 250,000 lives had already been lost as a result of the crisis. However, this one event sparked global outrage.

Liking And Likeness

Other tools include likeability and similarity, concepts that should be familiar from the initial discussion on attention. For example, in Influence, Robert Cialdini highlights research analyzing subjects that were critical of Darwinian principles.

Here, subjects displayed a better attitude towards evolution when they learned that George Clooney endorsed a book that took a pro-evolutionary stance. Mr. Handsome isn’t just able to sell you coffee but also convince you that you originate from apelike ancestors.

This is also relevant to climate change. Brandi Morris showed in Stories vs. Facts: Triggering Emotion And Action-Taking On Climate Change how a heightened risk perception of climate change was achieved in typically disengaged audiences when the messenger was politically conservative. This shows that the messenger matters as much, if not even more, than the message.

A Lack Of Options

Have you ever cried watching a movie? Many of us have. But did this trigger any action on your end? Most likely not. No matter if you witnessed an emotional narrative about an octopus displaying human characteristics as in the amazing film My Octopus Teacher or a story about HIV/AIDS as in Philadelphia, the chances are the piece created a strong set of feelings but did not provide options for you to translate these feelings into action.

Remember: the brain is minimizing friction. Researching ways to protect octopi after the movie takes effort. As such, and as trivial as it sounds, after motivating through emotional storytelling, we need to provide suggestions and options to make the desired action clear.

Too Many Options

Now, assume we have someone ready to change the world and we give them 50 things they can or should do. They will probably become paralyzed by too much choice.

In To Sell is Human, Daniel Pink explains how people go to places with a massive array of choices, but they actually buy from places with a small curated selection. No wonder then that Netflix is spending so many resources on its recommendation engine, which the company claims saves US$1 Billion a year.

The same applies here: we need to help frame peoples’ choices by providing them with a small but compelling range of options. Far too often, we point to the enormous challenges when the focus should be on the low-hanging fruit.

Don’t think there are low-hanging fruit? Think again. A shift in diet away from meat holds tremendous potential to lower greenhouse gas emissions. In the U.S., the worst 5% of energy producers account for almost 75% of the sector’s emissions, according to Wired.

Avoiding Unintended Consequences

Next, we need to phrase the choice or ask in the right way. One of my favorite parts in Influence showcases how messaging can go terribly wrong. For example, a state park informing visitors that there is rampant theft occurring led to an increase in theft. Why? Because the message is implying that everyone else does it, making it acceptable in a social context.

Another great example is provided by Jonah Berger in Contagious, where he shows how anti-drug and smoking campaigns failed miserably by implying that ‘all the cool kids do it’, no wonder then that the “just say no” campaign was a failure while the phrase itself became a pop culture joke.

The Benefits Of Uncertainty

One of the core elements in Nir Eyal’s model is the variable reward provided. Why would a variable reward be so powerful? Because it adds a level of uncertainty that the brain loves. Humans are curious by nature, and variable rewards take advantage of this curiosity perfectly.

Also, it prevents people from conducting proper cost-benefit analyses. Consider United’s Covid vaccination incentive: A chance to fly first class for free for one year plus 30 pairs of round-trip tickets. Why is this so powerful? When providing a fixed monetary reward for an action, for example, US$100 to get the Covid shot, you are certain of the outcome, and you can calculate if it’s worth it.

People are busy and might not consider the US$100 to be worth their time (we are discounting the health benefits in this example). Despite the probability adjusted value being significantly lower for a lottery, the approach is significantly more enticing.

Where is the value coming from? Your imagination. I have caught myself numerous times daydreaming after making a low-probability high-upside decision, imagining all the great things that would come out of this. Purely irrational yet entirely human. So why the additional round-trip tickets? To ensure that there are ongoing winners. It signals that winning is possible.

Gamifying The Process

But will taking one action change the world? What we need is long-term behavior change, which takes effort. And effort equals friction. So how can we overcome this? In Nudge, Richard Thaler explains the importance of fun and the need for nudges to feel like choices, not mandates.

Gamification is powerful in this regard. Dan Ariely has collaborated on a highly effective scale that is proven to create healthy habits and long-term weight loss. And it is not just the scale itself; it is a whole ecosystem of challenges, badges, color psychology, and social sharing that supports the user’s journey.

Options should be achievable and provide wins. People need to feel successful. This will further benefit long-term motivation as wins here will enable us to keep pushing. Gamification experts, such as Yu-Kai Chou with his Octalysis, provide excellent frameworks that could be put into practice here.

No one would continue to play a game when they never win a battle, find treasure, or experience any other kind of win. We need to apply this learning to our conservation efforts.

An Investment For Good

As per the Hooked model, after a variable reward is received, an investment should be demanded. This is important for two reasons. First, sequentially, this approach is smart given the willingness of people to reciprocate, as shown by Robert Cialdini in Influence. By providing a reward first, the likelihood of an investment is significantly increased.

Secondly, humans like to be consistent. This is why in real life, our actions drive our beliefs and not vice versa. Once we’ve taken an action and made a commitment, we are much more likely to follow through. This holds true even if we don’t tell anyone else.

However, the pressure increases exponentially once we make this commitment public. This is exactly the reason why so many health apps encourage sharing: Once your commitment is out there, everyone can see it; ergo, everyone will see you being inconsistent for not seeing it through. Nir Eyal explains that neurologically speaking, everything we do is about escaping discomfort and public shame is highly uncomfortable.

A secondary effect is that of signaling. The more people take action and share it, the higher the social pressure and social proof. Similar mechanics can be leveraged to increase the ask. An initial action lays the foundation for more effort to follow, which is supported by the social context of one’s group. This tribalism, in my opinion, is one of the most powerful concepts to leverage behavior change.

The WXO Take-Out

- Both doom and hope can stimulate behaviour change provided the information is wrapped in a compelling story

- Narrative arcs have a major impact on empathy and decision-making, generating the emotional buy-in that drives action

- Tribalism is a powerful way to leverage behavior change

Click here to read the second part of Hettwer’s article, where he explores the need for the media and entertainment sectors to act regeneratively, and the power the industry has to create tribes and motivate communities to take positive action against climate change

Interested in taking part in discussions about experiences and the Experience Economy? Apply to become a member of the WXO here – to come to Campfires, become a better experience designer, and be listed in the WXO Black Book.