Do you think of time as a cost?

Or do you picture time as revenue?

In services, time is a cost. But when it comes to experiences, time is revenue. This difference comes down to one crucial concept: the Money Value of Time (or MVT).

But what does MVT actually mean? One example might be a coffee shop. You go into Starbucks and pay for your coffee, but you’re also paying for the time you spend there – think yummy mummies on their morning meet, the student writing their dissertation, or the harangued worker looking for some lunchtime respite from the office. In Ziferblat café in London, you don’t even pay for your coffee – instead, you pay for the minute by the time you spend there.

When we understand MVT, we understand that time IS money – and that getting to grips with it is key if we’re going to prove the return on experience (ROX) of what we do. And when we can do this, we can also prove the value of the Experience Economy and skilled experience designers everywhere, boosting budgets and renown.

So for Campfire 35, who better to lead us through the MVT maze than Joe Pine, a WXO Co-Founder, author and godfather of the Experience Economy (minus the horses’ heads). Read on for your ultimate guide to putting a price tag on your experience – and creating new opportunities to charge for what you do.

Time, Money And Attention: The Holy Trinity

“The most precious resource on the planet is the time of individual human beings. The number-one competitor for their attention is the smartphone. And finally, while making money should never be the purpose of any organization, money is the measure of how well you fulfill your purpose.”

Joe Pine, author, The Experience Economy

Today every company in the world is competing against every other company in the world for the time, attention and money of individual customers. These are the three currencies of the Experience Economy:

- Time: is limited to 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

- Attention: is scarce and in a media-fragmented world, increasingly hard to capture.

- Money: is a consumable. Once it’s gone, it’s gone.

All of these currencies are interrelated. Time is money, but money is also time. Time is attention, attention is money, money is attention, and attention is time!

If you relate these concepts with one word, it’s “spend”. As experience designers, we should ask ourselves:

- Are your customers increasing or decreasing the amount of time spent with you?

- Do you have to exert ever more marketing and sales effort to gain the attention of customers, or do the experiences you offer create robust demand in and of themselves?

- Is the money customers pay you derived entirely from the sale of commodities, goods and services, or have you found ways to explicitly charge fees for various experiences?

The Time Value Of Money Vs The Money Value Of Time

The Time Value of Money (TVM) is the net present value of money that I can get in the future, based on the interest rate and so forth. As inflation increases, your TVM decreases.

But what’s important with experiences is to understand not just the Time Value of Money, but the Money Value of Time.

Pine measures MVT as expenditures per minute. For example, if you go to a movie, you’re charged on average around $12. Movies are on average around two hours. This works out to 10 cents per minute – a good experience.

However if you go to Disneyland and spend not two hours, but all day there – and you’re spending not $12, but over $100 – you get around 17 cents per minute. And if you go to Disney World, it’s around 23 cents per minute. So Disney World has twice as much value as a movie – even if a lot of that time is spent queuing, the perceived value of the ride makes it worth it.

The New Genres Of Experience

Ten cents per minute might be how we measure a successful experience – but some newer immersive art experiences, like the Museum of Ice Cream, cost around 42 cents per minute. Escape rooms get around 46 cents per minute.

“These new experiences have really upped the MVT. They show that people will often pay 40 to 50 cents per minute rather than merely 10 to 20 cents per minute. That’s part and parcel of the shift in the Experience Economy and of creating these entirely new genres of experience.”

Joe Pine, author, The Experience Economy

And it doesn’t stop there. If you get the top-priced ticket at the musical Hamilton, the MVT is around $5 per minute. Those who get tickets via the lottery system pay only 6 cents per minute – possibly the best value experience out there!

When it comes to skydiving, the amount of money you spend from the moment you jump out of the aircraft until you hit the ground is around $200 per minute – several orders of magnitude more than a movie because of how engaging and intense the experience is. You can even simulate skydiving and still get around $43 per minute.

And at the top end, Dennis Tito, the first multimillionaire to go into space, spent over $20 million on his eight-day trip – an MVT of around $1,750 per minute. Companies like SpaceX, Virgin Galactic and Blue Origin are now attempting to “democratize” space travel by selling it for a bargain $200,000 – but the experience only lasts for eight minutes, so the MVT is even higher.

These figures only reflect the publicly available information about the price tag of an experience, and not the additional revenue streams – food and beverage, parking, memorabilia – that run alongside them. But the moral of the story is that the sky’s the limit when it comes to how much money people are willing to spend on an experience, as long as you create something that engages and is worth that amount of money to them.

Why Is MVT Different Across Sectors?

We can also compare MVT across different sectors of the Experience Economy. Pine showed a graph where he’d measured the MVT of several of a client’s locations across the world. The MVT ranged from $2.43 to $1 per minute – impressive at both ends of the scale. But how can we explain the difference?

Our Campfire had several suggestions – some countries are more culturally amenable to experiences? Demand and supply? Size of experience? Cost of living?

Pine asked what if the experience is actually different per location? Maybe some do a better job of managing experiences, or of directing their workers to act, or of handling all the service aspects. This is something you can compare not only across countries or sectors, but across an individual company or companies. It’s a measure of the value that you create for individual customers.

Every quarter, The Economist does a “Big Mac Index”, where it compares the prices of Big Macs around the world to understand which currencies are devalued compared to the US dollar. This is a services index that can flex over time. Pine suggested doing a Starbucks coffee index that could function as an experience index. Even though Starbucks doesn’t charge admission for the experience, if you spend $5 on a cup of coffee and an hour there, guess what? You’re spending around five cents per minute.

You Are What You Charge For

As Pine set out in a recent article for Duke’s Dialogue, services are time well saved and experiences are time well spent.

“People want goods and services to be commoditized – to buy them at the cheapest possible price and the greatest possible convenience, so they can spend their hard earned money and their harder earned time on the experiences that they value.”

Joe Pine, author, The Experience Economy

If you think about the effect of time on economic value, the value that you create within your customers is predicated on two things:

- The functionality you provide, whether that’s the physical features of a good, the benefits of a service, or the sensations and engagement that you have with experiences.

- The net value of time. If you waste your customers’ time, you reduce the value of your product. But if you have time well saved, then you have a zero net value of time.

When you add these together, you can charge a premium for your experience. This is what Starbucks does. It doesn’t explicitly charge for the experience, but for the positive net value of time created by the ordering process and the time spent in a branch. This is why they can charge more to eat in than to take away.

“You are what you charge for.

If you charge for undifferentiated stuff, you’re in the commodities business.

If you charge for tangible things, you’re in the goods business.

If you charge for the activities you perform, you’re in the services business,

You’re in the experience business economically and explicitly, if, and only if, you charge for the time that they spend with you. So time is the currency of experiences once again.”

Joe Pine, author, The Experience Economy

There are hundreds of companies that are now charging admission, including places you would never expect it: retail stores, restaurants, tourism areas, manufacturers, and so on. Eventually all experience companies will charge explicitly for experiences, because you have to align what you charge with what your customers value – and that’s the time well spent that they get from you.

Getting Paid On Both Sides

Companies should therefore ask themselves: what would we do differently if we charged admission?

“If you don’t charge admission, chances are you’re never going to design that great, engaging experience. You’re sending the signal that this is not a place worth experiencing. But if you charge admission then you’re saying this is an explicit experience. This is a place worth experiencing.”

Joe Pine, author, The Experience Economy

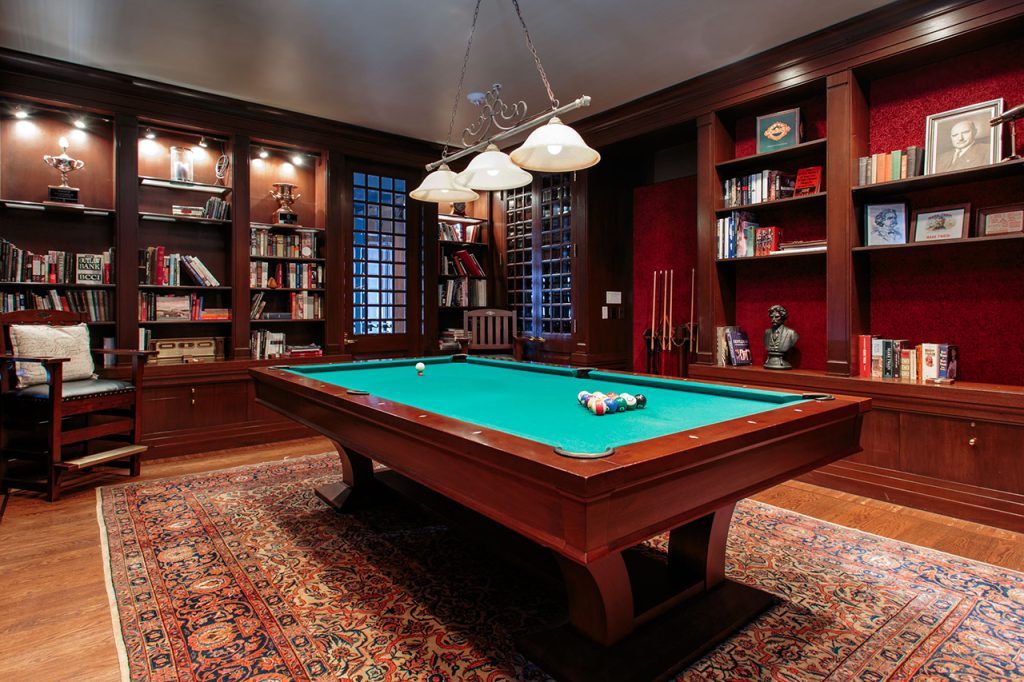

Pine gave the example of Wingtip, a male clothing store with the motto “solutions for the modern gentleman”. The owner created the “Wingtip Club”, a membership club above his store, and charged people a $3,000 initiation fee and $200 per month to be a member. The club includes a billiards room and cigar room and celebrates events like James Bond day.

“One of the things they’re able to achieve that I see increasingly is getting paid on both sides. On the one side, you’ve got consumers paying you explicitly for the experience, because you created a high money value of time. On the other side, you get businesses to pay you for access to those customers in your experience, because they want to be there. They do popular events where liquor companies come in and do liquor tastings, for example.”

Joe Pine, author, The Experience Economy

In Pine’s closing words:

“It’s all about getting a return on the experience that you create as a way of measuring how well you’re doing, of comparing yourself to others, and of figuring out how you can do even better. It simply recognizes that when it comes to consumers and experiences, time is money.”

Joe Pine, author, The Experience Economy

Charging For Outcomes

We then turned the conversation over to our Campfire. Creative strategist Susan Isko wondered why consultants were counted as a service rather than an experience.

“Business consultants are really in the transformation business. That’s time well invested. And that means charging for the outcomes that your customers drive. We have a co-authored article coming out in the January/February Harvard Business Review on transformations that ends with a paragraph on charging for outcomes. So transformations are the new you business.”

Joe Pine, author, The Experience Economy

James Wallman, CEO of The WXO, also called us back to experience design professor Bob Rossman’s comments in Campfire 4: The Difference Between Services And Experiences that a service is done for you, but an experience must be co-created.

“I think charging for outcomes is going to be the business most of us are in. Instead of charging X for a retainer, I’ll charge less, transform my client, then participate in the new profits of the business.”

Dennis Moseley-Williams, strategic consultant

The Money Value Of A Lifetime

The Australian Sport Commission’s Paul Templeman pointed out that the more invested a participant is in your experience to begin with, the more time (and money) they are likely to spend in it.

“If somebody participates in grassroots sport, they spend about four times as much in the professional side of the game – coming to matches, coming to the events – as somebody who didn’t participate in grassroots sport.”

Paul Templeman, Digital Director, The Australian Sport Commission

Pine agreed that your personal ROX and MVT could be closely tied together.

“If I think about sports and watching the game, going on social media with my favorite team, or buying a t-shirt, it all adds up. The intensity that you bring to that can bring a very high personal MVT, which might be an interesting measurement.”

Joe Pine, author, The Experience Economy

The Width Of An Hour

Could the way we experience time have an effect on MVT? Immersive experience designer Michael Badelt thought it might, as he explained in his concept of the “width of an hour”.

“We all know the expression ‘time flies when you’re having fun’. So even though every hour has the same length, 15 minutes in a theme park can feel like five minutes if you’re having fun, or like an exceptionally long amount of time if it’s just plain boring.”

Michael Badelt, immersive experience designer

This makes us think of Campfire 30: How To Design For Flow, and the definition that flow means “time having an elastic quality” when you’re engaged in it – as well as Wallman’s writing about time in his book Time and How To Spend It.

Perhaps MVT measures the “width” of an hour within its arbitrary length. The higher the MVT, the bigger the width. And if you’re wasting someone’s time or boring them, it’s much smaller.

Badelt also pointed out the problem with putting a price tag on a minute, when that minute might have a different “width”.

“When I worked for theme parks in Germany, people seem to immediately put a price tag on a minute. And when that price tag exceeds a certain value, normally one euro per minute, they’ll say oh no, that’s too expensive. So we try to stay below the one euro per minute marker. But what does that say about the quality of the experience?”

Michael Badelt, immersive experience designer

Creating Value For The Remembering Self

However, just as we’re notoriously bad at knowing what will make us happy, perhaps people are also bad at understanding the value of the experiences before them.

Wallman brought in the idea of the experiencing self and the remembering self, pointing out that people find it hard to understand the value they will get from remembering the experience in the future.

“People don’t yet realize that the experiencing self is going to have that pleasure right now, but the remembering self is going to have it for much longer. Perhaps you can’t afford it right now. But if you do, the value that it will give you will last not just for today, but for the next 40 years.

James Wallman, CEO, The WXO

The WXO Take-Out

MVT might seem like a complicated concept to grasp at first – but it’s actually really simple. Time is the currency of experiences; time well spent is what people will pay for; so the more functionality and net zero value of time you can give people, the more they will pay for your experience.

In Wallman’s words:

“The trend of the move from materialism to experientialism, the rise of the progression of economic value, and the fact that people are valuing experiences more and more: all this will continue. These are long-term structural, not cyclical, shifts in our economy.

At the same time, the pandemic has made people think about life and death in a more powerful way, and so they are suddenly more aware of the value of experiences and more willing to spend money and time on them. I think that if we can build MVT, this will only go up over time.”

James Wallman, CEO, The WXO

Interested in taking part in discussions about experiences and the Experience Economy? Apply to become a member of the WXO here – to come to Campfires, become a better experience designer, and be listed in the WXO Black Book.